This spotlight looks first at novelists and poets in British Columbia speaking out against oil sands transport in our province. Then I zoom out to broadly reference other authors whose works are either inspired by or are directly about environmental fallout from fossil fuels. This spotlight is just an overview due to article length–but I always appreciate feedback if you want to point me to works not mentioned. From ground or well to wheel, fossil fuels top the list of global warming causes (EPA/Planet Save), followed by methane emissions, deforestation, and dairy/meat industries. How do artists and authors talk about this? Poets generally just come out and say it, though creatively. Fiction can be more subtle but often is just as outspoken. Storytelling is diverse, so you’ll find a spectrum of voices. Living in a eco-rich temperate rainforest next to a delicate ocean, and in a place that is also at the center of oil sands controversies, I am inspired to pay attention to this crisis by looking at reactive poetry and fiction.

Bitumen

At some point, many authors put down the pen and get on their feet to continue to raise their voices for the planet. I’m reminded of Rachel Carson, David Attenborough, Wangari Maathai, John Muir, and many others. Never a very outgoing or loud person, it took me a while to get involved with marches and speaking out, mainly because I’m shy. My immersive knowledge of the area in which I live now–which is the unceded traditional territory of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations–began over ten years ago, when one of the first things I did when I moved to Canada was to go to Burnaby’s Shadbolt Theater to see a presentation with Ian McCallister, of Pacific Wild, and Andrew Nikiforuk, author of Slick Water, Tar Sands, and other books. They talked about Enbridge’s Northern Gateway proposal, which sought to build twin pipelines from the Alberta oil sands to Kitimat, BC. Ian discussed the danger to the northern rainforest’s wildlife, and Andrew covered the ins and outs of mining and extracting bitumen. I was so moved by their knowledgeable presentation that I went home and read all I could about the oil sands operations in Alberta. This was over ten years ago, when the Northern Gateway project was still a thing. Back then I was learning all I could. The Northern Gateway had so much opposition. And rightly so.

Between 2010 and 2013 I wrote an 11-part series about the Great Bear Rainforest, which looked at how bitumen was produced; how it would be dangerous to ship the oil via supertankers in the storm-ridden and sometimes narrow Pacific Ocean channels leading to and from Kitimat, BC; how unsafe pipelines and oil spills could be; how having supertankers on the west coast of BC could challenge and utterly destroy natural ecosystems at work; how well-to-wheel emissions of dil-bit were 18-21% higher than U.S. conventional crude; how economically infeasible this long-term investment would actually be; and how awful this project would be ecologically–using so many natural water resources, total destruction of much of Canada’s Boreal forests, dangerous chemicals, and tailings pond waste. I explored the flora and fauna it would affect: black and grizzly bears, wolves, old growth rainforests, thousands of salmon-spawning waterways, and marine life (including a chapter on wild salmon). I also wrote two chapters about people of the rainforest, including an interview with a college student arranging a paddle around the islands to raise awareness of the pipeline proposal. (A PDF is available for anyone interested, but many of the research links have since expired.)

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau rejected the Northern Gateway, but lately has been supportive of the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion, which also transports diluted bitumen (dil-bit) from Alberta. Oil sands transport is not new. Albertan oil deposits were discovered in the late 1940s, with the first Trans Mountain pipeline completed in 1953. In 2004 Kinder Morgan built a second pipeline, beginning at Hinton, Alberta and running to Hargreaves, BC. After this project was completed in 2008, Kinder Morgan filed another expansion application in 2013, which would run between Strathcona County in Alberta to Burnaby, BC, increasing the amount of oil transport from 380,000 barrels a day to 890,000 barrels a day, and also requiring 12 new pumping stations. The expansions do not speak well for transitioning off fossil fuels or any climate treaties, and in fact, according to Vice, the oil sands in Canada could collapse by 2030. The federal government, however, is buying Kinder Morgan for 4.5 billion dollars. Imagine putting that much into research and development of cleaner energy and the jobs that could come with it.

On May 29, 2018, the Canadian federal government announced its intent to acquire the Trans Mountain Pipeline from Kinder Morgan for $4.5 billion, which is expected to be completed in August 2018 pending approval. The federal government does not intend to remain the permanent owner of the pipeline, as it plans to seek outside investors to finance the twinning project. If the government cannot find a buyer before the consummation of the purchase, it will carry out the purchase via a crown corporation, and operate it in the meantime. The eventual owner will be indemnified by the government for any delays or hindrances to the project that result from legal actions by provincial or municipal governments. The government will also have the option to cover costs or purchase the pipeline back if the new owner is unable to complete the project due to legal pressure, or, despite reasonable efforts, cannot complete the project by an established deadline. (Source: Wikipedia)

Just going up the road a few blocks, we have a grand view of the Burrard Inlet. So it’s a “hey, this is in my backyard” type of worry, though, for me, I have great care for people everywhere, so I’d be equally worried for any project going through anyone’s backyard. It’s just that being in close proximity provokes way more awareness of what it’s like being here, feet on the ground, looking at it. Another controversial oil sands project is the Keystone XL, running to the United States.

Poetry Against Oil Sands

Throughout the last few years, I’ve had the great opportunity to work with authors who speak out against oil sands. My first work began in 2011 during the launch of 100,000 Poets for Change, an international event happening in the third weekend of September. The goal of the event is to simultaneously around the world promote peace, justice, and sustainability. I had worked with Michael Rothenberg since the late 1990s. If anyone could pull off such a big project, it was him, along with his partner Terri Carrion. The event isn’t just for poets. It’s for authors, dancers, musicians, and other artists. Hundreds of cities around the world take part each year. I’ve tried to include Vancouver in the mix since its launch.

In 2011, I was still a babe in Canada. I hadn’t met many folks yet, and my permanent residency was only three years old. In 2008, I had immediately begun working as a coordinator at a river stewardship program, however, so got my sealegs wet with many marches to protect wild salmon–from Vancouver to Victoria, including paddling with a group down the Fraser River to raise awareness of wild salmon. Because I had worked with that group, I tried to think of something I could do, personally, to combine poetry and activism. Since the 1st 100,000 Poets for Change event took place around River’s Day, I worked with one of Canada’s top environmental lawyers, Fraser Riverkeeper’s Doug Chapman, as well as with the city of Vancouver and the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup, to clean up one of Vancouver’s dirtiest beaches, False Creek East. I enlisted poets and other folks from Vancouver. Doug was very ill back then, and could barely do it, but he came out to speak at the cleanup. He’d spent his life fighting contamination in Canada’s waterways. We cleaned the beach during the day, along with dozens of volunteers, and then held a reading that evening in Vancouver’s downtown east-side, at the Carnegie Centre. The reading included Christine LeClerc, who had brilliantly imagined The Enpipe Line: 70,000 km of poetry written in resistance to the Northern Gateway pipeline proposal. Other poets from the project read as well, including Elaine Woo, Stephen Collis, Garry Thomas Morse, Alex Leslie, Wil George, and Rita Wong. It wasn’t surprising that I’d run into most of these people again throughout the years.

A video of the poetry reading is at Talon Books.

Christine went on to publish Oilywood, of which David Seymour remarked:

In Oilywood, corporate oil interests Kinder Morgan, El Paso, Eagle Ford and Peabody Energy become dramatis personae, villains in an all-too-real play on the world stage. These characters flaunt an ethic of ‘can implies ought’ with a dispassionate, journalistic reportage, but between their actions a lone voice bears witness to, reflects upon, and implores us to heed the wreckage caused in this epic theatre. This voice sings with vigilant clarity and resolute grace despite such overarching resistance to its song. Leclerc deserves bravos andencores.

See Christine reading from Oilywood:

In the summer of that year I also marched in protest against Kinder Morgan’s expansion proposal for the Trans Mountain Pipeline. We marched from a small park down to the Kinder Morgan refinery on the Burrard Inlet and listened to a few speakers, including a young girl named Ta’kaiya Blaney, from the Sliammon First Nation, who sang a couple beautiful songs and gave a heartwarming and intelligent speech about the problems she has seen and experienced first-hand with how the oil sands operations are ruining the water, the animals, the fish, the air quality, the land, and her people.

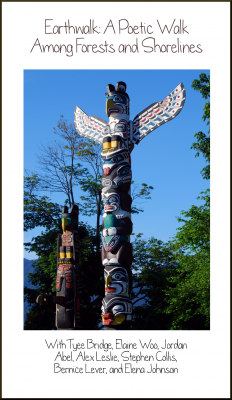

In 2012, I again formed a 100,000 Poets for Change event, this one an “Earthwalk” through Stanley Park, where we would stop and read poetry as we overlooked the Burrard Inlet and Vancouver Harbour views. We stopped at totem poles and under big trees to read poetry. We were saddened by an oil tanker sitting in the inlet that day, but it’s not an uncommon sight. In attendance were Tyee Bridge, who seemed to be quite the expert about the cultural and environmental heritage of the park, Elaine Woo, Jordan Abel, Alex Leslie, Stephen Collis, Bernice Lever, and Jeremie Marion. Plenty of others joined us in the walk too. I worked with False Creek Watershed Society, which does these walks each year. From Tyee’s excellent guiding, and the wonderful environmental poetry, I created a chapbook, which is still available for purchase as an e-book. In the past I printed this book at home on either hemp or 100% recycled paper and bound it with Japanese stitching. The book is dedicated to Doug Chapman, who had died not long after he spoke at the beach in 2011.

Included in the chapbook are parts of what Tyee sent me. It’s one of his guide speeches that day, broken into prose:

Included in the chapbook are parts of what Tyee sent me. It’s one of his guide speeches that day, broken into prose:

III. The Pipeline

Which brings us to oil.

Kinder Morgan sends diluted bitumen, dil-bit,

From the Fort McMurray oil sands to the Westridge Terminal

In Burrard Inlet, in Burnaby.Oil tankers go right under the Lion’s Gate Bridge:

About 75 tankers per year.

That’s 350,000 barrels per year out of that Burnaby pipe.Kinder Morgan wants to push it to 700,000.

They want to double carrying capacity in the pipeline

And triple the number of tanker transits to 228 per year.The only pipeline shipping crude from Edmonton to BC

And Washington—the Chevron Burnaby refinery, Cherry Point.

Herring spawn habitat. Among many other things.

The bitumen is watered down with benzene

And other petro-carcinogens.

“When a dil-bit spill occurs, the toxins evaporate into the air

and the heavy oil sinks.”Burrard Inlet has already suffered crude (and canola) oil spills.

The 2007 pipeline rupture sprayed 250,000 litres of synthetic crude

Into a Burnaby neighbourhood, 78000 litres

Sluiced into Burrard Inlet, fouled 17 km of shoreline,

Coating seaweed, birds, starfish and barnacles.Kinder Morgan and others involved were fined a total of $550,000.

It cost K-M $15 million to clean up.

But clean-ups don’t bring back

dead kelp beds, ducks, and starfish.

While all the readers contributed poetry about the importance of healthy ecosystems in our area of Canada, and the rest of the world, Stephen Collis read an excerpt from Almost Islands–“an extended meditation on literary ambition and failure, poetry and politics, choice and chance, location, colonization, and climate change – the struggle that is writing, and the end of writing.” Part of the threshold song:

If an oil spill come

if a river

if some coastal waters

coil about islets

tanker cringed

well as any manner

it will be done

and any seal’s death

diminishes meany cormorant’s

any otter’s

any salmon’s

any orca’sbecause I am involved

in all the water world

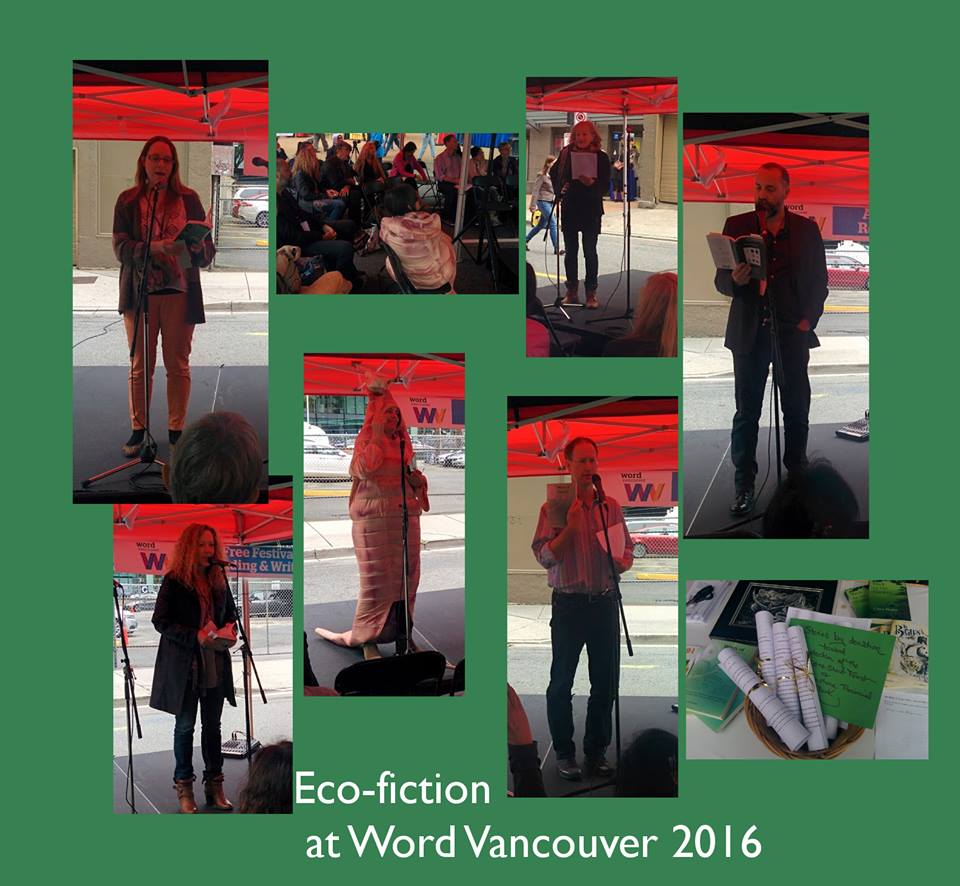

I have been in touch with several of the poets since then, particularly Stephen Collis, who joined me at Word Vancouver 2016 (western Canada’s largest literary festival) at the Eco-fiction Community Garden, along with Claudia Casper, Michael Donoghue, Katie Welch, and Anneliese Schultz.

Stephen read from his newest book, just out that summer, titled Once in Blockadia. Stephen chronicled in The Vancouver Observer how he had received a court injunction and lawsuit:

At one point, after reading a blog I had written, Kinder Morgan’s lawyer told the court that “underneath the poetry is a description of how the barricade was constructed.” My “poetry” had become evidence.

Before all this I had been writing a book of poetry about walking in the Anthropocene — walking along pipeline routes and proposed pipeline routes, and the strange and threatening paths they cut through our environments. It included walking through the Alberta tar sands and the alien “environment” created by that complete removal of every land formation we might recognize (it is, amongst other things, the construction of a vast desert in the middle of the boreal forest).

There is a tradition of descriptive landscape poetry, celebrating the beauty of the natural world, which I wanted to update for an era in which we have the capacity, and it would seem the tendency, to completely destroy certain landscapes.

Stephen sent me a new poem recently, which he wrote after the May 29th announcement that Trudeau was buying the Trans Mountain pipeline:

Curse Sonnet

One day

as the forests burn

as the rivers slow

thick with the sludge

of spilt oil

and the oceans press

their plastic waters

lifeless

to the gummy shore

under the scorched sky

their children will curse them

their children will curse them

their children will curse them

their children will curse them

Another advocate poet, whom I haven’t met yet, but hope to someday, is Valeen Jules. Valeen Jules (Kā’ ānni) is a determined young Indigenous warrior from the Nuu-chah-nulth and Kwakwaka’wakw Nations. She is a political organizer, motivational speaker, spoken word artist, black snake killer and ”overeducated extremist” across Turtle Island. Originally from Kyuquot, she now resides on Snuneymuxw territories.

Having been to so many of these marches against oil sands, whether Kinder Morgan or Northern Gateway, I get a lump in my throat watching her speak. Her work is so inspiring. Just see for yourself:

I also chatted with BC poet Lorna Crozier, particularly about her book The Wild in You, which was illustrated by Ian McAllister, who had been at the speaker event I attended seemingly so long ago. She stated:

Perhaps one of the greatest gifts of trees, particularly old trees draped with moss, is the silence they give to those who move quietly among them. That silence comes from the ocean, too, when humans are not roaring across the waters. One of the things that governments aren’t addressing is the destruction of that silence if tankers are allowed to use the rain coast as highways for the shipment of oil. Even if there isn’t a spill, acoustically tankers will destroy this pristine place. Fish aren’t deaf, whales need quiet to hear each other’s songs. Can this place not be a sanctuary of quiet for the creatures that call it home? Somehow Ian’s photographs capture the silence of this place he calls home. Among the images that his camera finds you sense a bodiless lack of noise. To try to find words to create a poem seems almost a sacrilege. Yet I think of what the writer Gary Snyder insisted: “some things can only be said in poetry.” If you’re a poet, you must say them. That’s what I’m after. What can my small voice do to protect this vulnerable unique wilderness? When I was there, I thought I’d lay my old body down in front of any tanker that came near. My words, too. I lay them down.

A Short Piece on Advocacy and Art

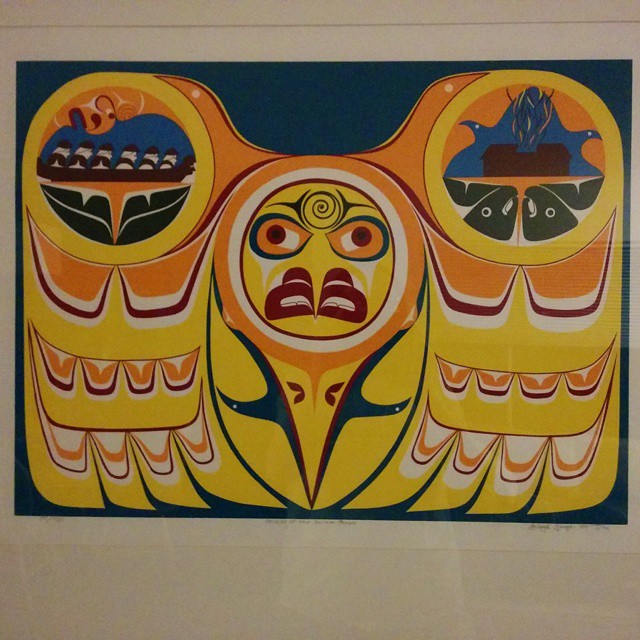

In the late summer of 2014 an “Art for Unis’tot’en Camp” benefit auction took place; the camp was part of Wet’suwet’en (Big Frog Clan). The Unis’tot’en were actively trying to stop pipeline work on their unceded territory, and were, I think, in their fifth year by that point. The auction allowed artists and authors to donate work to be bid on, and the funds would help get the camp through the winter. I won the auction for a beautiful print by Floyd Davis, titled “Origins of the Salmon People.” I also donated some copies of my novel Back to the Garden.

I spoke with one of the event organizers, Freda Huson, who said:

We found out about pipelines proposed for our territory along widzinkwa (Morice River). We decided as a clan that we did not have skills to do peaceful and safe demonstrations. We constructed a cabin in the GPS route of Enbridge and PTP. So invited groups like indigenous environmental network, Ruckas Society, council of Canadians, to assist in organizing our first annual action camp. seventy people attended first camp. The camp was intended to develop permanent structures to create a community. [My interview previously appeared at bcrainforest.com, which is now under new ownership.]

I was inspired by the concept of art and fiction helping to fund such a project. The camp was on the ground, literally blocking pre-work for the pipelines, which was already happening despite the fact the Northern Gateway was still under review and had not been officially approved.

Enbridge’s Northern Gateway wasn’t, of course, the only proposal around, nor the only pipeline company. As mentioned earlier, Kinder Morgan’s existing Trans Mountain pipeline, another, was recently sought to be acquired by the federal government in Canada (expected buyout in August 2018), a surprise after Prime Minister Trudeau had made promises to cut Canada’s greenhouse gases. Wikipedia has a good summary of Canadian pipelines here. Another from Siteline is here. Some amazing photography of the oil sands is at Ryan Jackson’s site.

Fiction and Oil Sands

One of the first pieces of fiction relating to Canadian dil-bit, that I became aware of, was the children’s book Spirit Bear, by Jennifer Harrington. I finally got a chance to talk with her in 2014, after I began this site, and she said:

The Northern Gateway Pipeline would be devastating to this area, because of the potential for a spill of bitumen oil, either from a leak in the pipeline itself or an accident by one of the tankers that would be transporting the oil from Kitimat to China through a network of narrow waterways. I did a tour of the Prairies last November that ended in Fort McMurray, so I took the opportunity to visit the Suncor Oil Sands project while I was there. I was amazed by the number of smokestacks at the site; in fact, they resembled a small city, and a very polluted one at that. I’ve attached the photos I was able to take from the road, the same photos I was detained for taking by the guards on duty, who pulled me over and questioned me, and told me I was not allowed to take photos of the plant. I found this strange, as there are guided tours of the facility offered in the summer. I felt there was a strong chance that my phone might have been confiscated if they had suspected my true purpose there, which was to report on the pollution cause by the project. I wasn’t able to enter the plant to see the tailings ponds on the other side, but I have seen aerial photographs, and I understand that they cover 176 square kilometres and contain billions of litres of contaminated waste water used in bitumen extraction and processing.

Spirit Bear celebrates a rare and iconic black bear that is born with a recessive gene that makes its coat creamy or white. Also called the Kermode bear, the spirit bear lives in the delicate, rich, and threatened ecosystem of the Great Bear Rainforest in British Columbia, Canada. The book is written by Jennifer Harrington and illustrated by Michael Arnott, and tells the story of a young spirit bear named Annuk, who falls into a river and is swept away from his mother. His journey home is a harrowing experience, complete with predators and trials, but also new friends and new understanding about the world he inhabits – the Great Bear Rainforest.

Another BC author, Katie Welch, wrote The Bears, which was revised in 2017 as Ursocrypha: The Book of Bear. When an oil pipeline in Northern British Columbia ruptures, the ensuing environmental disaster precipitates a crisis for activist Gilbert Crow, Arctic researcher Anne McCraig, and a young idealist named Jonathan Fuhrenmann. They converge on the troubled community at the heart of the disaster in a desperate, passionate attempt to save the bears they love. The dramatic stories of three bears are intertwined with the lives of the environmental activists and offer a glimpse into the spirituality and beliefs of the natural world. A race against time, this spiritual journey leads them on a path that forges in their hearts a new morality for an anthropocentric planet and a profound respect for nature.

I spoke with Katie in 2015. She said:

I began by imagining what Kitimat and the Great Bear Rainforest would look like if the pipeline were built. I have worked in and travelled along the proposed pipeline route. Simply imagining the land being cleared to make way for the pipeline affected me viscerally. My heart was sore, in some part for the loss of beautiful wilderness for human enjoyment, but in much greater part for the disruption of sensitive ecosystems and the animals and plants living in them. The human debate around whether or not the pipeline should be built seemed to me supercilious and selfish–what about all the other life forms? I imagined what a pipeline rupture and spill would be like for the totemic animal of Northwestern BC–a Kermode or Spirit Bear.

It was nice to personally meet Katie later when she came to Vancouver for a reading, and again I joined her one Christmas at her house in Kamloops for coffee. She’s a remarkably talented musician and writer.

A Broader Look

The 100,000 Poets for Change events included short story writing contests with themes such as solarpunk and climate change. The 2014 contest on climate change was wildly successful, enough so that I had plenty of great material for an anthology, which became known as Winds of Change: Short Stories About Our Climate, published in 2015. While a few short stories mentioned oil, it is through this contest that I met author Robert Sassor, also the winner of the contest, with his story “First Light,” an emotional story of a woman grieving the death of her son. We see that her grief goes beyond just her son’s loss:

We stare at a painting of an Inuit man under the ice, surrounded by jellies and constellations of tiny lights. The whole painting is blues and grays and beautiful. The hunter seems to be about to throw a spear underwater, legs and arms outstretched like a dancer. “I remember talking with Jacob about climate change,” I say, “about how Inuit hunters on Baffin Island are falling through the ice on their way to traditional hunting grounds. It’s getting warmer there, and the ice is too thin—people are dying while trying to provide for their families.”

Val looks at me, surprised. “Is that what inspired this?”

I shrug. “I’m just trying to tie the pieces together.”

One piece that stands out is of a bird. I figure it’s a cormorant. You painted a silhouette of it airing its wings—looking remarkably like a crucifix, with oil dripping from its body against a bright, orange sky. It is a simple piece compared to some of the others, but it makes me think about the sacrifices made at the hands of our folly.

I also got to know JL Morin, who contributed a chapter of her novel Nature’s Confession, a story of teenagers in the future doing what they can to save the planet from continued ecological devastation.

Earth orbited Sol below. Any smiled. She steered the ship deftly toward the future-past they sought. The spaceship pierced the Earth’s atmosphere. They glided over the putrid ocean, gray with oil and toxic waste, to rocky terrain, and landed with a thud. Any hoped she’d programmed for the right age. She prayed they didn’t land in the time of the dinosaurs. She opened the hatch, her tail protruding through a hole in the back of her space suit. The foul smell of pollution pervaded the atmosphere even here, up north in Alaska. (Nature’s Confession)

Anneliese Schultz contributed her heartwarming and humorous story “How to Make a Proper Insalata”:

Drenched and shaking. Tripping through bunchgrass and sage. Day night day, and Bear becomes memory becomes dream becomes touchstone. As I pound across frozen fields, Bear is the drumbeat; when I spy the footprints that will mean I find my step-father, Bear will be my cry of relief. Tonight, now, under Ponderosa pine, I am falling into righteous sleep, the thought of Bear my blanket and my tent.

Vanilla. Wait, pause on the sleep. How can I be smelling vanilla? Sitting, I open my arms, breathe in. Okay, I remember. Remember as if it was in another Age—Stone, Pre-Cambrian, Industrial, Oil, Post Fuck-up. Which would be when we were realizing the destruction that spun from our spiraling desires. When we began to duck them all, past present future; began to cover our eyes and shield our fragile heads. When still we squinted sometimes hopefully for hope, believed we would survive.

Many of the stories in Winds of Change explored oil as a big culprit for greenhouse emissions.

If you are interested in related fiction, my recommendations are Fred Stenson’s Who by Fire, Kathleen Dean Moore’s Piano Tide, Lydia Yuknavitch’s The Book of Joan, and John Atcheson’s A Being Darkly Wise.

Other novels have been written about oil, including Mei Mei Evans’ Oil and Water, which, according to the University of Alaska:

Set against the Exxon Valdez wreck in 1989, “Oil and Water” explores the American Dream in a fictional Alaska fishing town whose well-being is threatened, perhaps forever, when an oil tanker runs aground in the Gulf of Alaska.

In 2011, PBS’s Gabrielle Zuckerman interviewed Nigerian novelist Helon Habila’s about his Oil on Water:

Nigerian novelist Helon Habila comes out of this tradition, where politics and literature are closely intertwined. In Habila’s latest book, “Oil on Water,” the rookie journalist, Rufus, treks into the foggy backwaters of the Niger delta in search of the wife of a British oil executive kidnapped for ransom by a militia group whose stated goal is to bring the environmental destruction of the oil industry to the attention of the government and the world.

Though it’s not directly about oil, Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach Trilogy, as Macleans stated, has some backstory:

There’s always an element of chance in a pop culture moment, when something moves from cult appeal to mass attraction. But the backstory of how Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach series became a bestselling trilogy and a Hollywood film has more seemingly random aspects than most. Take the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico and VanderMeer’s love for St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge in northern Florida, combine them with one spectacular fever dream, and the author’s three novels (Annihilation, Authority and Acceptance) acquire a certain inevitability.

The Guardian had a great article in 2011 titled “Can Fiction Change Our View of Oil?” In the article Richard Lea gives other writers and journalists some nods, including Simon Jeffery, Tim Gautreaux, Rose Tremain, Joanna Kavenna, China Miéville, Robin Yassin-Kassab, Mohammed Hasan Alwan, Alain Mabanckou, and Simone Lia. Resilience notes the post-oil novel and mentions authors Andreas Eshbach, John Seymour, James Howard Kunstler, and even reaches back to Orson Welles, Douglas Adams, and John Taine. There’s always the novel Oil! by Upton Sinclair and Frank Herbert’s Dune. Futurism Media suggests:

There is a world where leaders fight over an arid, dessert land where fuel lurks below the sand – fuel that, if those warring nations lost, all society would collapse. We’re living in it. Dune and oil are more common than previously thought.

Jane Ciabettari at The Daily Beast introduces us to Rick Bass’s All the World to Hold Us:

The oil men in the novel are obsessed with finding oil and gas and striking it rich. What else drives them? “I think at that level the acquisitive hunter-gatherer gene influences them more than riches,” Bass said. He hasn’t been in West Texas and the region of Mexico at the base of the Sierra Madres where the novel is set in nearly thirty years. “For me, now, it’s all memory and imagination.”

I’m just touching the surface here, and I’m sure that there are hundreds of other novels that either speak directly to or are evolved from an oil situation. When I spoke with Omar El Akkad about his novel American War, we talked about dwindling fossil fuels:

Mary: As you pointed out, American War is about a second civil war in the United States, this one driven by a deep divide over the use of fossil fuels in an era of global warming. While the book is speculative, this scenario seems to be a likely outcome if things don’t improve—and with Trump at the wheel, it seems fossil fuels have a leader who will promote them, which goes against the grain of many Americans’ ideas of a more sustainable future.

More and more, it seems that speculative novels such as yours are more realistic than not. There is now a faded line between a potential frightening dystopian scenario and what might become reality due to where we are at and where we are headed. Quill & Quire even said about your novel “It has gone from being dystopian fiction to a work of historical naturalism before it’s even published.” Do you see your fiction as not stranger than truth? Do you think it’s a weird time to be writing speculative fiction?

Omar: I’m adamant that I never set out to write a book about the future. I realize how that sounds, given that American War is set about half a century from now, but at its core I think it’s a book about what has happened and what is happening now, not what will or might happen. I finished the first draft of the manuscript in the early summer of 2015, and I would have never guessed back then that the world would look the way it does two years later. I think the purpose of all good speculative fiction is to adjust in a grotesque manner the variables of the physical world in an effort to more easily explore something about what it means to be human. In that sense, it is a very strange time to be writing speculative fiction, in large part because the world seems every day to be headed in its own grotesque direction, one very few writers could have imagined –reality seems constantly on the verge of out-fictioning fiction.

An entire book was written titled Moby-Dick and the Mythology of Oil: An Admonition for the Petroleum Age, with the summary: Bob Wagner casts Melville’s epic novel as a lesson for the ages, one that is critical for us in today’s petroleum age. Wagner’s interpretation of Melville’s tale connects directly with today’s world, even with today’s headlines. Readers concerned with the American economic experience and our relationship with the Earth will find much to ponder in Wagner’s illumination of the parallels between Melville’s time and ours.

A cursory look at this site’s database reveals several discussions about fossil fuels as well as dozens of related novels. It’s impossible to be exhaustive, but I hope this glance at poetry and novels gets you thinking. The time is now for turning the tide. We really have to speak out against the expansion of oil production, and in the meantime open our minds to using less energy. You can keep up to date with future thoughts on the Kinder Morgan situation at my blog.