Click here to return to the world eco-fiction series

About the Book

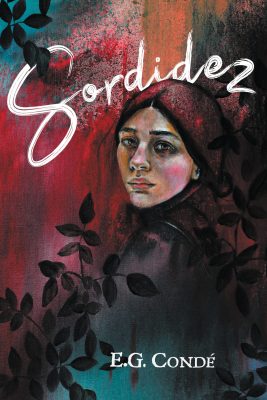

Sordidez is out in print and digital formats on August 1, 2023, by Stelliform Press. It’s an indigenous futurist science fiction novella set in Puerto Rico and the Yucatán by emerging author E.G. Condé. E.G. calls the novel an example of Taínofuturism, a term he describes as a counter canon of literary genres he grew up, with “class-climbing gentlemen or the sullen and suitorless dames of Charles Dickens or Emily Brontë novels,” which he felt, as a young student, he didn’t have much in common with. E.G. states that Taínofuturism “is inspired by the ancestral magic and enduring memory of the Taíno, the indigenous peoples of the Antilles… [his stories] imagine a decolonial future for Borikén, the Indigenous place-name for the U.S. territory known as Puerto Rico.” The genre rejects a return to a pre-colonial past.

Sordidez is out in print and digital formats on August 1, 2023, by Stelliform Press. It’s an indigenous futurist science fiction novella set in Puerto Rico and the Yucatán by emerging author E.G. Condé. E.G. calls the novel an example of Taínofuturism, a term he describes as a counter canon of literary genres he grew up, with “class-climbing gentlemen or the sullen and suitorless dames of Charles Dickens or Emily Brontë novels,” which he felt, as a young student, he didn’t have much in common with. E.G. states that Taínofuturism “is inspired by the ancestral magic and enduring memory of the Taíno, the indigenous peoples of the Antilles… [his stories] imagine a decolonial future for Borikén, the Indigenous place-name for the U.S. territory known as Puerto Rico.” The genre rejects a return to a pre-colonial past.

Condé’s brutal, mystical, and deeply felt speculative debut lifts up a vision of Indigenous resistance and renewal in the face of climate change and colonizers. … The author’s depiction of Taíno culture is profound, his evocative images of a land in ruin are visceral, and the grief and sheer determination expressed through his characters is often so vivid as to be overwhelming. The result is a beautiful blend of futurism and magical realism that delivers a hopeful message of human resilience.”

-Publishers Weekly

Chat with the Author

Mary: First of all, it’s great to meet you. Can you let readers know more about yourself?

E.G.: I like to think of myself as a “professional” nerd. The kind that reads comics, plays videogames, and does voice-acting for tabletop RPGs. But also, the geekier academic type that you might find at MIT, where I live another life as a social scientist who studies tech. My day job title is something like Cloud Anthropologist, because I have spent the last eight years studying the environmental effects of server farms in the United States, Iceland, Singapore, and Puerto Rico.

I go by Steven or Esteban (the E in my pen name, E.G. Condé). My grandmother used to call me Esteban because it is very difficult to say Steven if Spanish is your first language, but also she was protesting my mother’s decision to give me such a generic American name.

Mary: I’m a big fan of new genres and read that you are one of the creators of Taínofuturism. Can you explain what that is?

E.G.: In high school, I struggled in my English classes. Partly because I was a slacker, but more likely because it was difficult for me to connect with the characters, worlds, and storytelling traditions of the “literary canon”. I didn’t have much in common with the class-climbing gentlemen or the sullen and suitorless dames of Charles Dickens or Emily Brontë novels. The British may be the architects of the language I read and write in, but they aren’t my ancestors. That led me to wonder if Latine/x people were capable of producing literature worthy of canonization. In my artistic and creative practice, I hope to undo this literary invisibility, attempting to answer what stories for Latine/x readers by Latine/x writers look like.

Taínofuturism is my counter canon. It is inspired by the ancestral magic and enduring memory of the Taíno, the indigenous peoples of the Antilles. My stories imagine a decolonial future for Borikén, the Indigenous place-name for the U.S. territory known as Puerto Rico. In primary school we are taught that the Taíno went extinct, defeated by disease and the horrors of Spanish colonialism. Today, the U.S. government does not recognize the Taíno as an indigenous people. Rejecting this erasure of their heritage, revivalist communities across the Caribbean are rebuilding the language, customs, and traditions of the Taíno from the fragments that survived colonialism.

Taínofuturism is my contribution to this enormous effort. Rather than call for the return to a pre-colonial past, the futures I imagine reject purity and the boundaries that have long prevented our peoples from flourishing (ex. religious intolerance, racism, colorism, heterosexism, cissexism). I envision this genre as a celebration of the many influences that make us Antillean including the contributions of West African peoples like the Yoruba and Igbo, who have long been downplayed or devalued due to racism.

My end goal is to create fiction that inspires us to reclaim and remake the Antillean world in our own messy image. Taínofuturism is a decolonial dream of space canoes, time machines made from gourds, cybernetic Carnival masks, nonhereditary chiefs who are Black and very queer, and heroes who overcome empire by decolonizing themselves.

In Puerto Rico, where U.S. fiscal policy and cryptocolonialism are actively displacing my people and exterminating their way of life, this decolonial dream feels especially timely.

Mary: I agree, and it’s exciting. We’ll talk about your new book Sordidez. Would you call that an example of Taínofuturism? What’s happening in the novel?

E.G.: Sordidez is a concrete example of Taínofuturism. It is there in the aesthetics of the technology depicted in the book, somewhat like Marvel’s Wakanda Forever, but most of what makes it Indigenous futurism is subtle rather than flashy.

Sordidez begins in Puerto Rico, where a band of rural people must rebuild their lives in the aftermath of a devastating climate change fueled superhurricane. Abandoned by their government, Vero Diaz and his sisters rise up to remake their society and protect their people, but the tradition gets in the way. Vero is driven away from the island, rejected by his people for being trans, despite everything he has sacrificed and accomplished on their behalf. This leads him to a career in journalism. He ends up in the Yucatán years later, covering a story about a refuge for people displaced by the hydrophage, a climate weapon unleashed by a dictator to turn the jungle into a desert. The situation is familiar and painful for Vero. He investigates further, setting him on a collision course with the Loba Roja, a Maya revolutionary who seeks to remake the Yucatán in the image of her people. As powerful, neocolonial forces plot to destroy her, Vero must make an impossible choice about his future and the future of Puerto Rico.

At the heart of Sordidez is a rekindling of Taíno-Maya networks that predated Iberian colonialism. The essence of this book is exchange and metamorphosis. The exchange of ideas about what freedom looks like in the twenty-first century. The metamorphoses required to overcome the ongoing grip of colonialism in Latin America.

Mary: Do you identify with Vero; how so?

E.G.: Vero is certainly a part of me. As a cis person, there are aspects of Vero’s experience that I can never know intimately, but much of him is directly pulled from my life experience as a Boricua who never fully fit in no matter how hard he tried. Being queer in a society with machismo and a very traditional Christian ethic that frames queer existence as a heretical blasphemy—that part of Vero I can totally relate to.

Vero displays a resilience I admire. His journey as a character builds on the resilience he cultivated following his gender transition. He finds that after becoming a man, he must then become something else entirely to fulfill his destiny and help the people that he loves. People that he has learned to forgive for their hatred and misunderstanding of who he was and who he is becoming. Given the epidemic of violence against trans people in Puerto Rico, the decision to make Vero trans is not something I take lightly. I am grateful to have had the help of sensitivity readers and friends who could provide deeper insight into the trans experience to guide me as I shaped this character and his arc of many metamorphoses.

Mary: Writing Indigenous heroes in stories is uplifting and refreshing. Why is this so important?

E.G.: Indigeneity is a complicated concept. Sordidez is set in two very different regions with very different histories and ideas about what or who counts as Indigenous. In the Yucatán peninsula which spans present-day Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras, that history is painful and complicated. Sordidez features characters from Mayan-speaking peoples, including coastal Maya, highland K’iche’-speaking Maya, and Tzeltales of Chiapas. Unlike Puerto Rico, indigeneity is more formalized in these countries. One of the characters in Sordidez is something of a pan-Mayan revolutionary, a nod to a long history of coalitional organizing to combat dispossession of land and language, institutional exclusion, poverty, and the genocides of Maya peoples perpetrated by the Spanish and the Central American “republics” that followed their departure.

In Puerto Rico, where the local government and the US government do not formally recognize the Taíno as an indigenous people or tribal group, the idea of a contemporary or near-future Taíno hero might seem like an impossibility for some readers. And that is the point. Vero, the novella’s protagonist, provides a blueprint for a new indigeneity that does not resemble the colonial stereotype. I think it is super important today to trouble this commodified trope of the noble savage, especially when you have Hollywood studios cashing in on “Indigenous futurism” while shamelessly appropriating the cultures of others. James Cameron’s most recent Avatar film is an example of this. (The word for chief in Avatar is Tsahìk, which suspiciously resembles the Taíno word for chief, Cacique or Kasike.)

Mary: Having voices from within the experience is more genuine and meaningful and, as a reader from the outside, it’s a story that I want to read. Can you explain more about the hydrophage?

At MIT, I encounter a lot of well-meaning folks who are dreaming up quick and easy techno-fixes to our climate catastrophe. These climate moon-shots include everything from direct carbon capture to injecting the atmosphere with reflective sulfate compounds to reverse global heating. The global scope of these proposed technofixes should give anyone who reads science fiction pause. What I find more troubling is that we have to turn to them at all. Our governments have decided that capitalism is more precious than our planet. Rather than slow the profit engine that is devastating our environment while lining the pockets of others, we are entertaining these radical, potentially-cataclysmic “hail-Marys”. Calls to halt or regulate research into these technologies are growing.

The hydrophage comes from this genealogy of terraforming hubris. In Sordidez, the hydrophage begins as a climate salve, a technology designed by rich nations for poorer nations to reverse the desertification that their emissions caused. The solution backfires with devastating consequences for the inhabitants of the Yucatán peninsula. And just like that, climate salve becomes a climate weapon, wielded by the Caudillo, the novella’s despotic antagonist, to inflict suffering on his own people and maintain indefinite power. For me, hydrophage is a parable for what could go wrong if we trust too much in technology and ignore the radical societal changes that our climate moment demands of us.

E.G.: What ties do you have with Puerto Rico, and do you go back there often? What are some of your experiences there?

I am a diasporican, which is important to highlight. I visited the island throughout my life to spend time with my grandparents, attend Quinceañeras, funerals and family reunions. During the pandemic, I lived there to conduct research on infrastructure resiliency in the aftermath of Hurricane María. But I was not raised in Puerto Rico. I spent most of my life in New England. Nonetheless, my experiences on the island are precious to me and have influenced who I am greatly. Some of my earliest memories are at my grandmother’s house in the mountains, where I hunted for coquíes, tiny tree frogs that sing as dusk breaks (they make a cameo in the book). I was told by family that my grandmother and her mother were descendants of “indios”, which is not an unusual saying in our culture, but one that captivated my young imagination. As an adult, I have spent a great deal of time searching for the answer to that mystery, seeking out the Taíno in museum displays, archaeological sites, my DNA, revival groups or in remote places where their petroglyphs can be found in guano-stained caves or on boulders along our many streams. Sordidez is a story about re-indigenization inspired by my own journey of searching for what indigeneity means and looks like in twenty-first century Puerto Rico.

Mary: Are you working on any new projects?

E.G.: Sordidez was never meant to be a novella. I originally conceived of it as a short story to set up the backstory of a minor character for a novel set in the same universe that I am tentatively titling Supercoherence. The novel, which I have been writing and rewriting for over a decade, explores the relationship between quantum computing and shamanic divination in a near-future setting that spans many continents. I have also been working on something entirely different, a paranormal horror thriller called Syzygy, which I can only describe as a bizarro mashup of X-Files and House of Cards, inspired by my brief stint as a political organizer and my obsession with UFOlogy and eyewitness accounts of the paranormal.

Mary: These projects sound interesting and cool, so best wishes in finishing them. And thanks so much for being a part of this spotlight series.

About the Author

E.G. Condé (he/him/Él) is a queer diasporic Boricua writer of speculative fiction and fantasy. Condé is one of the creators of “Taínofuturism”, an emerging artistic genre that imagines a future of indigenous renewal and decolonial liberation for Borikén (Puerto Rico) and the archipelagos of the Caribbean. His short fiction appears in Anthropology & Humanism, If There’s Anyone Left, Reckoning, EASST Review, Tree and Stone, Sword & Sorcery, Solarpunk Magazine, and FABLE: An Anthology of Sci-Fi, Horror & The Supernatural. When he isn’t conjuring up faraway universes, you might find him hiking through sand dunes or playing 2D JRPGs from the 1990s. Follow him on twitter via @CloudAnthro or Instagram @Boricuascribe.