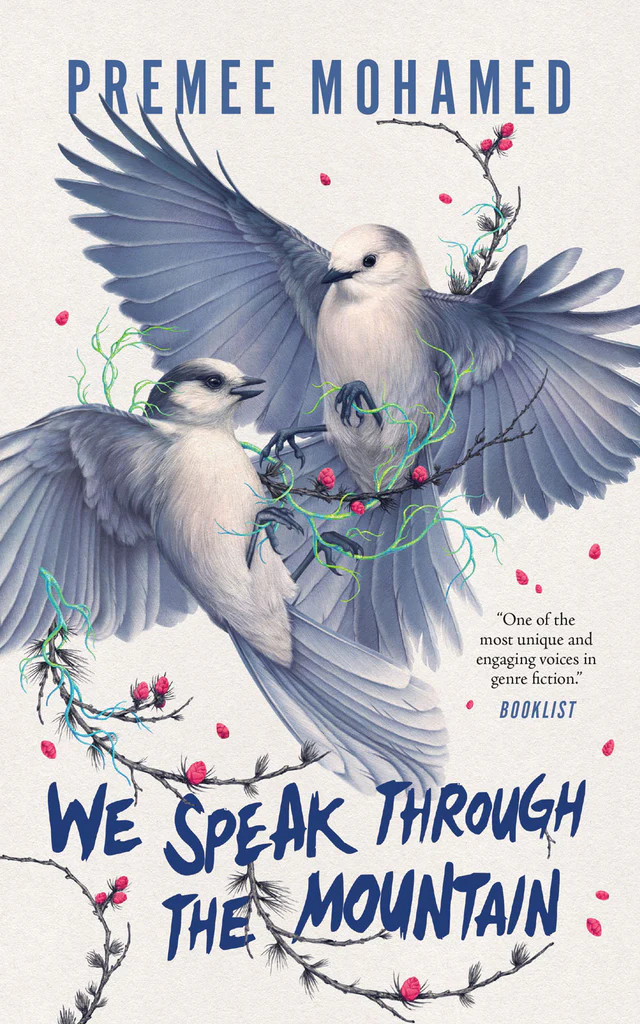

I was happy to talk with Premee Mohamed about her sequel to The Annual Migration of Clouds—We Speak Through the Mountain (ECW Press, 2024).

Traveling alone through the climate-crisis-ravaged wilds of Alberta’s Rocky Mountains, 19-year-old Reid Graham battles the elements and her lifelong chronic illness to reach the utopia of Howse University. But life in one of the storied “domes”—the last remnants of pre-collapse society—isn’t what she expected. Reid tries to excel in her classes and make connections with other students, but still grapples with guilt over what happened just before she left her community. And as she learns more about life at Howse, she begins to realize she can’t stand idly by as the people of the dome purposely withhold needed resources from the rest of humanity. When the worst of news comes from back home, Reid must make a choice between herself, her family, and the broken new world.

In this powerful follow-up to her award-winning novella The Annual Migration of Clouds, Premee Mohamed is at the top of her game as she explores the conflicts and complexities of this post-apocalyptic society and asks whether humanity is doomed to forever re-create its worst mistakes.

Mary: It’s so exciting to see another novel by you—We Speak Through the Mountain, which is a sequel to The Annual Migration of Clouds. After our last interview about Clouds, had you planned at that time to write a sequel? Also, do you suggest that people read the prequel first?

Premee: Nooooo, I never had a sequel planned! In fact, I think I’ve mentioned this before—I was adamantly and explicitly anti-sequel. I wanted the ending of the first book to be so ambiguous I’d get angry emails from people; I wanted it to be pure possibility. It was my publisher that approached me about writing a sequel and doing the exact thing I did not want to do, which was continue Reid’s story and answer some of the questions I was determined to remain unanswered in the first book, because the uncertainty was the point. I didn’t want readers to know any more about what was true and what was untrue than Reid did. She was going off to explore, and the story felt complete to me. With that said, because I was twisting around so much, and brainstorming with my editor, about what the second and third books might look like, I think we actually did come up with something that captures the spirit of the original book and raises, I hope, just as many questions as it answers. As with any series, I do recommend that people read the first book before reading the second one; they’re connected narratively and in terms of chronology, so the second book won’t make sense unless you know what happened in the first book.

Mary: In the sequel, the main character, Reid Graham, continues to search for what she has heard may be a utopia, Howse University, but it isn’t exactly a utopia. Whenever I think of utopia, I think of “no place” and some of Ursula Le Guin’s blog thoughts on it, such as: “Both utopia and dystopia are often an enclave of maximum control surrounded by a wilderness…Good citizens of utopia consider the wilderness dangerous, hostile, unlivable; to an adventurous or rebellious dystopian it represents change and freedom.” Does this idea fit into your story?

Premee: Absolutely. I’ve always been a fan of fiction that attempts to present either a dystopia (slightly easier) or a utopia (slightly harder), because it’s essentially axiomatic that no utopia is a utopia for all of its inhabitants; it can’t be. There’s simply so much variation in human personalities, desires, relationships, ambitions, backgrounds, values, and so on that the ineradicable, adamantine level of control needed to maintain a dystopia or a utopia should be intolerable to at least some of the population. Where it becomes really interesting to me narratively, as Le Guin points out, is that these -opias are often if not always surrounded by some type of wilderness, which you see in Huxley’s Brave New World and Zamyatin’s We as well as, to a lesser extent (because of the surveillance!), Orwell’s 1984. The wilderness is supposed to be a threat, inimical to human habitation; it resisted domestication, it is hostile, repulsive, dangerous. At the same time, because it is unknown, it is fundamentally irresistible. The human impulses of curiosity and exploration are and should be what eventually bring down every planned perfect society. Collectively, we have a desire for novelty that can border on the obsessive. Reid, who thinks she’s pretty familiar with the regimented life, is shocked (I think) to discover that there are people who believe quite the opposite: she’s from the wilderness, she represents the unknown, the uncontrolled, the unpredictable, and the unreasonable. She has a lot of growing up to do as well as a lot of what we in the environmental field call “expectations management.”

Mary: Another idea I always wonder about is the repetition of human mistakes, as in the book’s description: “Premee Mohamed is at the top of her game as she explores the conflicts and complexities of this post-apocalyptic society and asks whether humanity is doomed to forever recreate its worst mistakes.” Can you talk about the findings, without spoiling the novel?

Premee: Again, one of those cases where I didn’t write the book description and found myself thinking “Oh yeah, that actually was exactly what the book was about!” I guess the question is: What do we think were humanity’s worst mistakes? Both my writer and scientist friends joke about this constantly. The discovery of nuclear weapons? Or the internal combustion engine? Crawling out of the ocean to breathe air? There are so many candidates. I think in both books, though particularly in the sequel, I’m trying obliquely to refer to the mistakes of mindset and priority—of intention rather than effect—that we’ve seen pretty much since the advent of industrialized society. The tendency to assign in-groups and out-groups and become hostile to out-groups to the point of declaring that they’re a danger to in-groups and must be eliminated (i.e. the source of most conflicts and almost all extremism). The tendency to discount future liabilities and overvalue present assets, leading to resource over-exploitation, colonization, environmental degradation, and active repression of people seeking out alternatives. Tendencies toward classism, ableism, ageism, misogyny, and other bigotry. Bunker mentality—capitalist mentality. In both books, there are places described that actively and consciously fought back against some of these mistakes; there are also places that leaned into them, figuring that it was the only way to survive in the manner in which they wanted to survive.

Mary: Last time we talked, we honed in on hopepunk, a genre of speculative fiction that gives readers a sense that our future can be positive rather than all gloom and doom. Would you say that the new novel continues in this mode?

Premee: I think so? I hope so. When I think of hopepunk, I first and always think of punk—the willingness to get dirty, do the work, circumvent the system, get around or through obstacles instead of trying to pretend they don’t exist and circumscribing your life accordingly. Trying to be nice and accommodating is not the punk way. And I think Reid embodies that in both books: she wants change, she hopes for a better future, but she’s also trying to figure out what the work is that she can do in order to make those changes. And she’s got little patience for people who don’t think there’s work to be done—either because the problems don’t need solving or because they’re too big to solve. I think we’re seeing even now, in various areas, at various scales (things like solar power uptake, reforestation projects, marine protected areas, etc) that problems that seem too big to solve in one swoop can be chipped away at if you’re stubborn enough.

Mary: Any book tours planned (like to Halifax?).

Premee: No book tours, sadly! (I would love to return to Halifax though! I had a brilliant time there in 2022.) However, I’m looking forward to discussing and signing books at the Eden Mills Writers’ Festival in September and the Surrey International Writers’ Conference in October! I also have an event at Bakka Phoenix Books in September with a fellow Caribbean author, Suzan Palumbo.

Mary: Sounds fascinating! And if you’re ever back in Halifax, let me know.

Premee Mohamed is a Nebula, World Fantasy, and Aurora award-winning Indo-Caribbean scientist and speculative fiction author based in Edmonton, Alberta. She has also been a finalist for the Hugo, Ignyte, Locus, British Fantasy, and Crawford awards. Currently, she is the Edmonton Public Library writer-in-residence and an Assistant Editor at the short fiction audio venue Escape Pod. She is the author of the Beneath the Rising series of novels as well as several novellas. Her short fiction has appeared in many venues and she can be found on her website.

Recently Premee learned that her novel The Siege of Burning Grass is a finalist for the Ursula K. Le Guin Prize and that her short story collection No One Will Come Back for Us is a finalist for a World Fantasy Award. She also recently won an Aurora Award for her short story “At Every Door a Ghost”.