Written and © by Annis Pratt and previously published at her blog, The Worlds We Long For

Last summer I wrote an essay about whether climate warming will cause the extinction of the human species, so when I came across an article by Lucy Jakub on “Wild Speculation: Evolution After Humans,” I was interested in her startlingly idiosyncratic take.

I spend many happy hours facilitating Socrates Cafes, where people ask philosophical questions and examine philosophical premises in an open-minded and open-hearted manner. As I read Jakub’s survey of speculative writing about the end of the species, I found myself querying the writers’ premises about how we got to this pass.

Geologist Dougal Dixon (who assumes in those innocent years that it is a new Ice Age that will do us in) devotes his 1981 After Man to a scientific study, based on evolutionary genetics, of life forms that might evolve when we are gone.

“Humans go extinct because we lose our evolutionary advantage by adapting our environment to our needs, rather than the other way around. When the resources needed to maintain our civilizations run out, we are unable to adapt quickly enough to survive. Crucially, nothing takes our place, and the planet reverts to an Edenic state, uncorrupted by knowledge.”

Let’s look at this philosophically: Dixon considers our capacity for adaption the fruit of our advanced cognition, which isn’t advanced enough to prevent us from depleting our own ecosystem. But if this is so, is it our knowledge that corrupts us or poor choices about how to use it?

We did not all make those choices. Only a small (if powerful) elite of westernized humans – mostly male and mostly industrialists (think of Wordsworth! Think of Dickinson!) propose such a preposterous idea. Their presumption that human beings are separate from and in control of nature serves their bottom line and profit motive, while the rest of us have come to realize that we are more like ruinous genes running amok within it.

Jakubs describes the “Speculative world-building,” of science fiction as a way to explore solutions to our environmental predicament. But Pierre Boulle, in his 1963 Planet of the Apes, is less worried about what is happening to the environment than what is happening in the pecking order, namely “man’s fall from dominance,” while Brian Aldiss, similarly, frets in his 1962 novel Hothouse that human beings have ceded control to (of all things) vegetation.

Do you see the pattern here? Nature (apes, plants) is a terrifying external force usurping human power/over everything.

As we move into recent decades, however, Jakub notes that the “bourgeoning environmental movement led to a new genre, Eco-fiction, whose authors -Ursula K. Le Guin, Louise Erdrich, and Barbara Kingsolver- are especially beloved – mourned not the fall or humanity but the degradation of nature and our lost connection to it, and whose utopias didn’t necessarily include humans.”

Is it just a coincidence that the three authors she cites are women? Or is the premise that nature is a degradable “other” less universal than it seems?

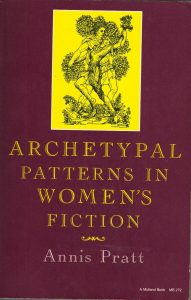

When women novelists write about nature there is a significant gender difference in our premises. In the 1980s I analyzed more than 300 novels by women to compare women heroes’ quests to those outlined (for “man”) by Joseph Campbell. What I found was that while his male hero took women as both “other” and embedded in an alien and dangerous realm of nature,” women saw themselves as deeply integrated in and interdependent with the green world around them.

In recent years, both men and women have embraced the Gaia hypothesis that our planet is an organism within which we and all other life-forms live and must maintain a mutually beneficial balance. Meanwhile, Eco-fiction has become a widespread and popular genre to the extent that Jim Dwyer’s Where the Wild Books Are: A Field Guide to Eco-Fictionlists more than 1000 volumes from all over the world.

Mary Woodbury, its most thoroughgoing curator, describes “Eco-fiction (as) ecologically oriented fiction, which may be nature-oriented (non-human oriented) or environment-oriented (human impacts on nature). . .Eco-Fiction novels and prose zoom out to beyond the personal narrative and connect us to the commons around us – our natural habitat.”

Mary Woodbury, its most thoroughgoing curator, describes “Eco-fiction (as) ecologically oriented fiction, which may be nature-oriented (non-human oriented) or environment-oriented (human impacts on nature). . .Eco-Fiction novels and prose zoom out to beyond the personal narrative and connect us to the commons around us – our natural habitat.”

Ecology deals with the interactions of organisms within a system and takes human beings as one of those organisms. Eco-Fiction. in Woodbury’s definition, is connective and understands nature as our commons. How we are to do the work of that connection and how we are to take our rightful place within that commons are questions this excitingly speculative new genre raises in our minds and hearts through the deep truths of storytelling.