Click here to return to the series

In August, I kick off two parts of a feature that heads to Italy to talk with eco-authors there. Thanks to Antonia Santopietro for her collaboration on these features. Together we planned this article, which became big enough to break into two parts for the World Eco-fiction Series: Climate Change and Beyond, which travels around the world seeking stories set in different places. The authors talk about their ecologically oriented novels, short fiction, and poetry, providing insight to their localities, experience, and environmental issues, lifting our gaze to something outside our own back yards but perhaps reflecting on similar feelings that we all have. Though the authors sometimes write from Italy, of course, some of the fiction we concentrate on today takes place in the Central Alps, California, and the Aral Sea, on the border of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

The authors we meet today are Davide Sapienza, Elena Maffioletti, and Tiziano Fratus. I ask them each two questions: can they tell us something about their writing and most recent novels, and what it is like for them with the coronavirus pandemic happening? Join us again on September 11 when we conclude this feature by talking with Maurizio Corrado, Laura Pugno, and Claudio Morandini. Thanks to Antonia for working with the authors and translating their answers.

Davide Sapienza

Generally speaking, my books are not novels or nonfiction. Each is a genre on its own. That is how I chose it to be since the very beginning, after twenty years of being mainly an author of books about rock music and a long period of silence (1998-2004) in which I did not publish a single word, in either magazines or books. My work is a geopoetic approach to the world. And the vision is that we are part of nature. This is how the ancient philosophers, the Tao and the Indigenous worldview taught me. I am the opposite of the Cartesian cogito ergo sum. I am because I am: I breathe, I walk, I live, therefore I am. In my personal geopoetic approach–no protocols, no theories, practice, like in Zen, is the light I follow–everything blends in one continuous flow. So, every book I write tells me how to write it with its own mind, just like a song tells the songwriter how it needs to be honed and crafted.

A book is a literary voyage, and we authors in the trail of Mother Earth are the voyagers, inviting others to share the inner- and outer-scapes through our words and narratives. Biodiversity teaches us that each living being is different. That is how I see literature and books. Genres kill art. Genres humiliate people’s sensibilities, spoon-feeding audiences to sell. Selling is important, but it cannot be the vision.

The first creature that took shape from this way of seeing and worldview, was a non-chronological travelogue, where entry dates responded to the psychic voyage: I Diari Di Rubha Hunish (The Rubha Hunish Journals, 2004, written from 1996 to 2002, and then implemented with the final version of 2017). And from then onward, I practiced my artistic exploration in the wake of the geographical explorer open to whatever came next. Until I got, after a dozen major publications, to Il Geopoeta. Avventure nelle terre della percezione (The Geopoet. Adventures in the Land of Perception). This is the way the first literary cycle came full circle. I structured it starting from the long statement (Ch. 1, Geopgrahy Is Poetic), slowly moving through the cracks of a more fictional narrative, in the closing “opening” towards the future (Ch. 9, I Walk Across The Stars). This conversation with the stars comes after the reader has been invited to a sensorial experience through a fictional archetypal valley (based on a real one I live close to), then through the perception of the “thin Arctic light”, and then on a reflection on freedom for the enfant sauvage of Francois Truffaut, the paintings of Giovanni Segantini seen from a “self” in the snow while touring with his backcountry skis in Engadin, the evocative “lands of sound” of Neil Young, and the rock revolution we experienced in the latest part of the twentieth century. I love the ceaseless conversation of the traveler, drawing from nature and meditation, to discover a different way of moving through the world, pondering on details and feeling the relationship between the human experience and the landscape–the intimate geography, as Barry Lopez calls it. This style has allowed me to translate the book experience in my journalism, becoming the trademark of my cultural contribution. When I talk about experience, I mean it: I always brought my books to the audience mainly in the form of literary geopoetic walks: the “traveling audience,” reflecting my need to share more than one of selling a book, which goes by itself, eventually. The Geopoet is now the work that will ignite my next literary journey–which surfaced in earnest during the Covid-19 months–through a series of new stories and writings, some published in major newspapers and magazines and some to be released later in 2020.

The first creature that took shape from this way of seeing and worldview, was a non-chronological travelogue, where entry dates responded to the psychic voyage: I Diari Di Rubha Hunish (The Rubha Hunish Journals, 2004, written from 1996 to 2002, and then implemented with the final version of 2017). And from then onward, I practiced my artistic exploration in the wake of the geographical explorer open to whatever came next. Until I got, after a dozen major publications, to Il Geopoeta. Avventure nelle terre della percezione (The Geopoet. Adventures in the Land of Perception). This is the way the first literary cycle came full circle. I structured it starting from the long statement (Ch. 1, Geopgrahy Is Poetic), slowly moving through the cracks of a more fictional narrative, in the closing “opening” towards the future (Ch. 9, I Walk Across The Stars). This conversation with the stars comes after the reader has been invited to a sensorial experience through a fictional archetypal valley (based on a real one I live close to), then through the perception of the “thin Arctic light”, and then on a reflection on freedom for the enfant sauvage of Francois Truffaut, the paintings of Giovanni Segantini seen from a “self” in the snow while touring with his backcountry skis in Engadin, the evocative “lands of sound” of Neil Young, and the rock revolution we experienced in the latest part of the twentieth century. I love the ceaseless conversation of the traveler, drawing from nature and meditation, to discover a different way of moving through the world, pondering on details and feeling the relationship between the human experience and the landscape–the intimate geography, as Barry Lopez calls it. This style has allowed me to translate the book experience in my journalism, becoming the trademark of my cultural contribution. When I talk about experience, I mean it: I always brought my books to the audience mainly in the form of literary geopoetic walks: the “traveling audience,” reflecting my need to share more than one of selling a book, which goes by itself, eventually. The Geopoet is now the work that will ignite my next literary journey–which surfaced in earnest during the Covid-19 months–through a series of new stories and writings, some published in major newspapers and magazines and some to be released later in 2020.

It is difficult to pinpoint how the coronavirus affects me; the experience is still ongoing, the vision too fragile and fresh, the perspective not yet formed. But I can definitely say that though I always felt very aligned with a more natural and simple life (I have now lived for 30 years in a small mountain village of Val Seriana, Bergamo Orobian Alps–yes, the infamous valley devastated by the ineptitude of the Lombardia governance, an even more deadly virus). But these months proved that, when faced with themselves, people do feel the need to dig deeper into themselves, aspiring to a more serious approach in life. But because I always felt like that, those two months in many ways helped me to hit a new motherlode. This brought me to start afresh after the long and very demanding work that The Geopoet carried with itself for the best part of three years, intertwined with my journalistic work, The Geopoetic work (for Bodo2024, European Capital of Culture, including a project I devised on the field from 2016 to 2018 in the Arctic), The Geopoetic walks, and so on. Somehow, the coronavirus lockdown made me feel “useful” to this superficial society. I felt my audience even closer, I received emotional and thoughtful encouragement, and some people even asked wanted to hire me for my Geopoetic services for private events. It is a never-ending give and take, a flow of life, a relationship, a connection, that I strongly feel. One example is the long writing I recently published in Vanity Fair (Italy) about The Rights Of Nature, a theme I introduced in Italy nine years ago, by translating Cormac Cullinan’s book Wild Law. It has always been very difficult to get these things published in major and popular magazines; now, they are asking me about these niche subject that are, in reality, the subject and that the pandemic only proved, now more than ever, is the way to go. So, in a line, I would say that the coronavirus effect was to free the flow that was somehow hidden somewhere in my psyche.

Bio

Davide Sapienza is an author, geopoet, journalist (www.davidesapienza.net). All works and books are at https://www.lavallediognidove.it.

Davide Sapienza is an author, geopoet, journalist (www.davidesapienza.net). All works and books are at https://www.lavallediognidove.it.

Elena Maffioletti

Nature has always played a major role in my writing. In my novels I explore new and different ways of getting at people through words. This sometimes takes me further than my intention, and when this happens nature is usually there, in a permanent exchange of stimuli between author and words on one side, and words, images, emotion, and the reader on the other. Nature is present when a cathartic moment takes place or when an epiphany arises.

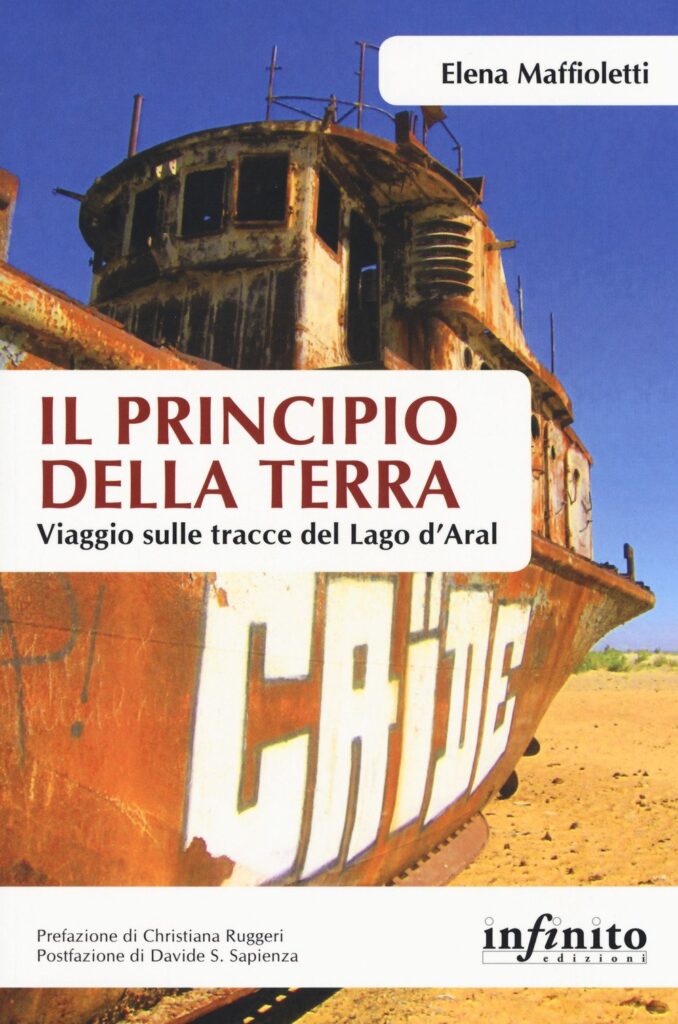

I grew up in a house on a hill surrounded by trees and fields; that was my closest environment as a child, and Nature is still the only place where I feel fully at ease. It supports and feeds my being a part of the Earth. That’s why Nature always accompanies the reader of my works. My most recent novel, Il principio della terra – Viaggio sulle tracce del Lago d’Aral (Where the Earth begins – In search of the Aral Sea) is the closest to eco-fiction I have written, being related to one of the worst ecological disasters in the world, the decrease in size and volume of the Aral Sea and consequent soil salinization and formation of a desert called Aral-kum. This was due to diversion of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers between the 1960s through 1980s to support irrigation for intensive cotton farming. In the same period, an island in the middle of the Aral Sea named Vozrozdenye (Rebirth Island) was used by the Soviets as a bioweapons testing range. Relics of laboratory complex now lie in the dust, just as rusty fishing vessels lie on the dry soil where a large part of the Aral Sea used to be, both on Kazakh and Uzbek sides. The landscape is dramatic and beautiful, a sort of primordial world, but pollution from pesticides and desiccation have had a terrible impact on the local ecosystem and population over the last 50 years. I traveled through Uzbekistan some years ago, and I was fascinated by the contrast between the richness of culture and tradition of the country and the dusty scenery of Lake Aral. The novel was born as a collection of short stories inspired by places and people I had met, but beyond my intention the stories joined each other like threads in a tapestry and formed a bigger one, a novel where everything is invented and real at the same time, which invites the reader to feel the territory and its people and become a part of it.

I grew up in a house on a hill surrounded by trees and fields; that was my closest environment as a child, and Nature is still the only place where I feel fully at ease. It supports and feeds my being a part of the Earth. That’s why Nature always accompanies the reader of my works. My most recent novel, Il principio della terra – Viaggio sulle tracce del Lago d’Aral (Where the Earth begins – In search of the Aral Sea) is the closest to eco-fiction I have written, being related to one of the worst ecological disasters in the world, the decrease in size and volume of the Aral Sea and consequent soil salinization and formation of a desert called Aral-kum. This was due to diversion of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers between the 1960s through 1980s to support irrigation for intensive cotton farming. In the same period, an island in the middle of the Aral Sea named Vozrozdenye (Rebirth Island) was used by the Soviets as a bioweapons testing range. Relics of laboratory complex now lie in the dust, just as rusty fishing vessels lie on the dry soil where a large part of the Aral Sea used to be, both on Kazakh and Uzbek sides. The landscape is dramatic and beautiful, a sort of primordial world, but pollution from pesticides and desiccation have had a terrible impact on the local ecosystem and population over the last 50 years. I traveled through Uzbekistan some years ago, and I was fascinated by the contrast between the richness of culture and tradition of the country and the dusty scenery of Lake Aral. The novel was born as a collection of short stories inspired by places and people I had met, but beyond my intention the stories joined each other like threads in a tapestry and formed a bigger one, a novel where everything is invented and real at the same time, which invites the reader to feel the territory and its people and become a part of it.

I can only imagine how my writing will be affected by the Covid-19, as I am about to start a new novel, but I haven’t begun it yet, just because of coronavirus. I live in Alzano Lombardo, which together with Nembro is one of the places most affected by infection in Bergamo area. During the last months, simply, I was not able to write a single word. All that was happening was too much. My mother got sick, relatives got sick, friends got sick, neighbours got sick; some of them were taken to hospital, others recovered after a long period of isolation and quarantine, and others did not make it and died. But, above all, there was a shared feeling of hallucination, like living in a permanent nightmare. I do believe this will affect my future writing, but I know I need time to process facts and feelings.

Bio

Elena Maffioletti lives near Bergamo. Novels: Sotto il cielo d’aprile (Under the April sky), 1999; Le Prigioni del Verde (Prisons of Green), 2003; Il ladro di parole (Thief of words), 2009; Bisclavret – Storia luminosa di tempi bui (Bisclavret – A bright history of dark ages) written with Vittoria Delsere, 2010; Lettere di Caterina da Siena (Letters of Catherine of Siena), theatrical work, 2014; Il principio della terra – Viaggio sulle tracce del Lago d’Aral (Where the Earth begins – In search of the Aral Sea), 2018. Forthcoming: Bisclavret II – I guardiani di Sabta (Bisclavret II – The guardians of Sabta), written with Vittoria Delsere.

Tiziano Fratus

Writing develops one’s own truth. Sometime this truth corresponds in time and rhythm to the truth as we know it in everyday life. Sometimes it differs and substitutes–at least, referring to the imaginary that writing sets and in the timing that the story needs. As far I’m concerned, in this diverse world, nature represents a vehement root, an impulse often innervating frameworks and choices of characters living in it.

Of course, there are several natures: for instance, the inner, the wild nature we can imagine in feral acts, such as the attack of a bear, the nocturnal song of a group of wolves–which digs the darkness of the Apennines–or the running up of an African beast.

Wild places are diminishing all over the world, and polar ice caps are melting, due to climate change. In a few decades they will be treated like the cautious game in Yellowstone or Yosemite parks.

Then there is the anthropomorphization of nature, which is what we built and allowed in the proximity of our civilizations, urban and suburban. This refers to a purified, graceful, decorative nature, which reveals surprises, though not perilous and no longer as wild as the Dante’s selva oscura, which covered whole spaces outside those walls that the medieval person could walk on.

Fragments, or labels of the wild world, survive in countries that sociology defines as the third and fourth worlds. Then we have kind of nature as we know it today, where naturalistic stories are set. Some examples are Le otto montagne (The eight mountains) by Paolo Cognetti; Neve, cane, piede (Snow, dog, foot) by Claudio Morandini; and La pelle dell’orso by Matteo Righetto. Finally, there is a fantastic and imaginative nature, as described by Mauro Corona in La voce degli uomini freddi or the funny and dramatic transformation of Han Kang, in The vegetarian.

In the two stories I’ve published so far, the novel Every tree is a poet and the Gothic fairy wood tale Waldo Basilius, the characters act in a strongly woody cosmos; in mechanisms that literary tradition has listed under the genre of fantastic or magical realism.

My poetry is different, due to the fact that my poems are drawn. They are designed as plant parts–the leaf, the tree, the seed–and to focus on a speculative aspect, putting characters in front of the great issues of human life. The nature of the landscape is alive and shapes our minds, but humans always try to rebel, giving a form, a substance, to his own need for freedom. Finally, my richest production belongs to new nature writing, an autobiographical and migrant writing that moves from one natural place to another: large monumental trees, country or regional nature reserves, botanical gardens, historic gardens. I wrote several operas that I renamed silvari (woodsbooks).

I’ve spent ten years writing my Giona delle sequoie, a big book devoted to the splendor and history of the Californian sequoias: the story of their discovery, the adventures of people who had fought to safeguard them, the travel notes I put together, and the foggy memories about my father and my mother, two figures crossing the entire book. It is a travel writing piece constantly evolving into meditation.

Regarding the coronavirus, I’d already been living quite a secluded life for a long time, and I can’t define myself as a pure hermit as my connections to the world are still alive, but I embraced the archaic and original meaning of the Greek word μοναχός (pronounced “mo-na-còs”) which means lonely person/lonely spirit.

I dedicate the time I have available practicing a spirituality. I’m now immersed in Zen Buddhism, a personal local version of it, spurious indeed, that I define silvobuddismo (forestal Buddhism) in a funny way, when not taking this word too seriously. That’s why I feel that I’m a spectator in this pandemic situation, though not disinterested since I experience feelings of fright, helplessness, and anger too, particularly arising for the inadequate action of our government in facing the disaster, especially in keeping doctors and nurses safe by providing personal protective equipment (PPE).

I’ve not sympathized with the rhetoric of the first period of lockdown when the refrain was ce la faremo, tutti insieme (together, we will make it), because it sounds like sweeping the dust under the carpet, while people were dying and are still dying in Italy and all over the world.

I can’t say if this will impact my writing, or how. Topics such as searching for silence and marginality of human beings in some parts of the world are the ones I deal with. I hope an invasion of catastrophic novels won’t derive from the pandemic, such as alternate histories or dystopian novels, because both cinema and television, over the past few years, have impacted us in great measure. Nor I do believe, what keyboard philosophers are saying, that the pandemic is a precious opportunity to change society and consumerism, by abolishing capitalism and so on. If we someday become safe from the pandemic effects, behaviors will probably be the same. We hope something better will happen, but we should not delude ourselves. As a matter of fact, it’s not that I distrust humans, but it seems to be in the order of things on the planet that everyone could ask for privileges that only a few grab.

Bio

Tiziano Fratus was born in Bergamo in 1975. He grew up breathing northern Italy landscapes, the great plain, and mountains. When his natural family dissolved, he began to travel, crossing and touching conifer woods in California and around the Alps where he coined the concept of Rootman (Homo Radix), practice Zen meditation in nature every day, and cultivated the discipline of Dendrosophy (Dendrosophia). In his twenty years of writing, he published a wide forest of words–travelogues, meditation books, novels, collections of poems–some by Italian publishing houses, such as Mondadori, Feltrinelli, Bompiani, Laterza and Einaudi, and some by independent ones. His poems have been translated into ten languages and published in many countries, while his photographs have been shown in solo exhibitions. Fratus is a newspaper columnist and the voice of the radio program Nova Silva Philosophica. He lives in a little house in the countryside with his long time partner and a dozen of cats. Website: studiohomoradix.com