Part V. Women Working in Nature and the Arts

Note: The novel The Bears was republished as Ursocrypha: The Book of Bear in 2017.

Mary: Katie, thanks so much for agreeing to an interview with Eco-fiction.com. Your book The Bears tackles a subject very close to my heart: What would happen if an oil sands pipeline project were built in the coastal Pacific temperate rainforest of British Columbia, in a portion that we call the Great Bear Rainforest–and then what would happen if there were a pipeline bust or a tanker spill? What led you to develop this scenario?

Katie: Hello Mary. It’s my pleasure to be interviewed by Eco-fiction.com. The Northern Gateway pipeline proposed by Enbridge Oil for northern British Columbia has been a contentious issue for almost a decade; it was announced in 2006. Proponents of the project claim that its economic benefits would outweigh any environmental costs, but Enbridge has a terrible track record of spills and negligence related to their projects. Those in favour of the pipeline have dollar signs dancing in their dreams. Their priorities are financial. All evidence and experience of oil pipelines and oil transport via supertanker points to the same conclusion: Pipelines break and tankers sink, with horrific consequences for the natural world.

When I wrote The Bears, I began by imagining what Kitimat and the Great Bear Rainforest would look like if the pipeline were built. I have worked in and travelled along the proposed pipeline route. Simply imagining the land being cleared to make way for the pipeline affected me viscerally. My heart was sore, in some part for the loss of beautiful wilderness for human enjoyment, but in much greater part for the disruption of sensitive ecosystems and the animals and plants living in them. The human debate around whether or not the pipeline should be built seemed to me supercilious and selfish–what about all the other life forms? I imagined what a pipeline rupture and spill would be like for the totemic animal of Northwestern BC–a Kermode or Spirit Bear.

Mary: This is a real threat we face now with the potential of Enbridge’s Northern Gateway Pipeline project, which would pipe bitumen oil from Alberta to Kitimat, BC, and then be loaded onto supertankers on the western coast. These super tankers would then need to navigate narrow and delicate channels leading to the Pacific, and then ship the oil to China and other Asian countries. A twin pipeline from Kitimat to Alberta would ship a condensate of chemicals and liquid that is needed to dilute the heavy oil–which is actually mined from the ground. Tell us, why is this oil so bad compared to lighterweight oil? And why is this particular rainforest so important to protect?

Katie: This is an excellent question. There are many reasons why bitumen, oil mined from the Alberta tar sands is much worse for the environment than lighterweight oil. The most devastating one is related to climate change–greenhouse gas emissions from oil sands projects are a massive contributor to the most pressing problem facing humanity today. Bickering about precisely how much the oil sands contribute to climate change is really moot. Unless there is drastic global reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, we are sentencing much of this planet, and millions of creatures that live on it, to death. Ironically, Canadian executives supporting oil sands projects point fingers at China and crow about how much worse of emitters the Chinese are compared to us–hello! That’s who’s financing oil-sands hungry projects like Northern Gateway!

Other environmental consequences of oil sands development include reckless overuse of fresh water, air pollution, water pollution (including carcinogenic toxins in the water), and disruption of areas of boreal forest on such a large scale that entire wildlife communities are decimated.

Expanding any fossil-fuel industry–coal, traditional oil, bitumen–compounds a problem that could lead to the next global mass extinction! It seems to me that, facing a crisis that threatens us all, we aren’t embracing the ingenuity and resourcefulness available to us to avert a genuine ecological catastrophe. Why not expand and explore the myriad alternative energy technologies available to us?

Any rainforest left standing on this planet is important to protect. Trees are the lungs of the earth, and we now know that rainforest soil is much more delicate and easily destroyed than our ancestors believed. The Great Bear Rainforest represents a full twenty five percent of remaining coastal temperate rainforests. It’s an ecological treasure.

If you think about the way this planet was colonized by humans, it isn’t surprising that the Northwestern corner of the last big landmass to be industrialized is still, by default really, intact. It’s still there because I think people are beginning to wake up to the importance of protecting the last wild places left standing. The question is whether we will wake up in large enough numbers, and in time. Personally, it boggles my mind that anyone today could look at the Great Bear Rainforest and envision destroying it for economic profit. I just don’t get it, the terrible hubris of humanity, that we could in any way improve on–or in the case of Northern Gateway, gamble with–the majestic perfection of nature.

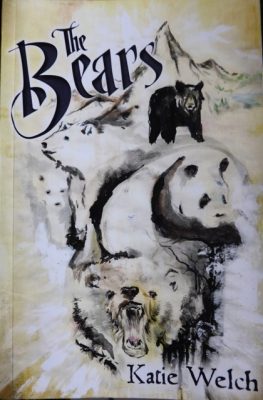

Mary: Your book is gorgeous inside and out. I was firstly impressed by the cover–and then by the unique structure of the book therein, where you give animals a voice and humans a totemic relationship with animals. How did you decide on this animistic style? I think it works well.

Katie: I love the cover of The Bears! The story behind it is amazing, and relates to the second part of your question. I began writing The Bears with the support and encouragement of my partner, Will Stinson; we hadn’t been together for long. When I needed a cover for my novel, Will mentioned that his then 22-year old son, Dylan, was a gifted artist.

I sat down with Dylan Stinson and gave him a brief synopsis of the novel, concentrating on the bear characters and the centrality of the oil spill to the plot. He immediately went home and painted the cover as it stands. I was flabbergasted when I saw Dylan’s painting for the first time. It was as though he had siphoned off something from my imagination and poured it into his art. The original is hanging on my living room wall. His painting includes four bear species, their images overlapping beautifully, suggesting that they are all one. In the bottom right hand corner of the painting, several coniferous trees bleed a sinister, black pool of oil.

I also asked Dylan to paint his vision of what the star constellations would look like if bears had created the mythologies behind them. That painting is reproduced in black and white on the inside of the book. The black and white reproduction doesn’t do this second painting justice–it is as startling and beautiful as the cover, and the original also hangs in my home.

The idea for The Bears came from a desire for people to consider bears, and by extension all wildlife, as equal stakeholders in decisions that will have great impact and consequences for non-human life forms. I asked myself why people automatically place human needs above those of animals. The answer, it seemed to me, is that people think they are better than animals, because of our higher thinking processes. One of the markers of our higher thinking is that we have spiritual concepts, faith-based visions of the world. What if bears had their own spirituality? The Bears begins with a bear-based creation myth. Several more mythical bear-based stories are scattered through the book.

After I created a Spirit Bear character, Moksgm’ol, who gets tainted and terrified by an oil spill, I started thinking about how other bear species are negatively impacted by humans. Sadly, another Canadian example came to mind immediately: polar bears. Tlingit was my next bear character, an adult female polar bear whose cub drowned due to lack of ice caused by global warming.

Yukuai, which ironically means ‘happy’ in Chinese, was the final bear character I added. Right around the time I was writing The Bears, the Canadian Prime Minister was given two (famously endangered) panda bears by the Chinese government. It irked me that these animals were being used as a symbol of international camaraderie, a bit of fluff to divert the public’s attention from international oil exploitation machinations. One day while walking in downtown Kamloops I found a fabric wristband on the sidewalk. The wristband was for the Cologne Zoo in Germany. I came home and Googled the Cologne (Kolner) Zoo, and discovered that the firebombing of Cologne in WWII had killed some, but not all, of the animals captive in the zoo at that time. Taken together, I thought all of these things more than merely coincidence. I decided to include a captive panda in my story, and the character of Yukuai was born.

The totemic relationships–a human connected with each bear–began as a tentative idea and evolved as the story evolved. A First Nations man, Gilbert, with a connection to a Spirit Bear, seemed natural, as did a big-hearted scientist studying polar bears, Anne. Jonathan’s relationship with Yukuai had to be temporally removed, but I liked the concept of a Nazi’s descendant being an open-minded, happy idealist.

Mary: Fascinating about these different bears! Your background involves the rainforest area and includes tree-planting. I was delighted to learn in an earlier conversation that you also worked with Charlotte Gill, who wrote the award-winning non-fiction book Eating Dirt, which was about planting trees. I adopted her at Vancouver’s book fair a few years ago and loved her book. Do you have any special memories of these times?

Katie: Tree planting was a big part of my young adult life. I planted for seven seasons, in seven provinces. Charlotte Gill did an absolutely brilliant job in Eating Dirt of describing life as a tree planter. Her non-fiction prose approaches poetry. Tree planting, for all its romantic reputation, is a brutal job and a difficult existence. As the person responsible for introducing Charlotte Gill to tree planting and securing her first job, I felt somewhat guilty while reading Eating Dirt–the author nearly perishes on several occasions. We were housemates at the University of Toronto as well; my last year was Charlotte’s first.

The season I planted with Charlotte, our crew was based in Northern Ontario. It was an unusual beginning to a season, because forestry union workers were pressuring silviculture companies to force planters to stay in portable Atco trailers instead of tents. Our camp consisted of almost a hundred planters staying in trailers in a muddy, blackfly-infested field. On the third day of the contract, a ‘greener’ (new planter) left a pair of socks drying on a propane heater. The trailer she was staying in caught fire and burned to the ground. It was an atypical, less than ideal planting situation. A lot of ‘greeners’ quit in the first shift or two that year, horrified by the working conditions and the intensity of the work. As I recall, nothing dampened Charlotte’s wide-eyed enthusiasm; she was equal to the great physical and psychological challenges of tree planting life. She embraced the experiences with singular zeal and resilience.

Mary: Related to the above question, bitumen oil expansion and deforestation are two big culprits in climate change–along with the energy it takes to develop crops for our beef industries. Having written this book, with an obvious moral imperative, how do you think environmental novels can make a difference? Have you received positive feedback on your book from readers who were not aware of the pipeline issue before?

Katie: So far I think the audience for The Bears has been made up of like-minded individuals. I think I’ve mainly been preaching to the choir. I do harbour a hope that the book will reach a greater audience and perhaps influence people who are unaware of the pipeline issue. The rise in popularity of eco-fiction, or environmental fiction, is a reason for optimism. Art is often a reflection of what is happening culturally in a society; sometimes it can also be prescient. Canadian photographer Alex MacLean’s photographs of the oil sands are shocking. They inspire us to be outraged by the magnitude of the destruction in northern Alberta. They force us to think about what is happening. I wanted something of this for The Bears as well. I gave the bears human voices because I want readers to identify with them, to consider what today’s environmental challenges are like for other living things.

Mary: Who are the people who influenced the way you write, and are you working on anything else right now?

Katie: I’m a voracious reader with a predilection for magical realism. As a young girl I read and reread Tolkien and C.S. Lewis. I love complex novels with many characters and cleverly interwoven plots, A.S. Byatt, George Eliot, Mordecai Richler. The timing of the release of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series coincided perfectly with my children’s maturation as readers, I think I’ve read the series a dozen times. The same goes for Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials series, another writer with an obvious moral imperative! I’m also a patriotic Canadian reader. I idolized Margaret Atwood while obtaining a BA in English Literature at the University of Toronto; I love the trajectory of her career. I am currently reading Oryx and Crake on Wattpad. I think Margaret Atwood, who has her finger on the pulse of popular culture, is an eco-fiction writer.

Two months ago I completed another full-length adult eco-fiction novel, Becoming Bees. I am currently querying literary agents and publishers with this manuscript. I hope to see it published in the near future! Becoming Bees is about a young man who claims he had a quantum transformation and spent a year living as a beehive. I am also writing my first series for young adults, Sarah Spellings & The Followers of The Grove. The first three chapters are up on Wattpad and free to read.

Mary: Katie, thanks so much for sharing your ideas and information about the Great Bear Rainforest and about The Bears. Your book is fascinating and unique. I hope it does reach far and wide, to people outside the choir as well. Best of luck in your future writings, and let’s please keep in touch!

Pingback:Interview with Katie Welch, author of The Bears - BC Rainforest

Pingback:Katie Welch Author Interview on Eco-Fiction | Writer Katie Welch