Back to the Indie Corner series

This month’s Indie Corner is the first that features one of my relatives. W.R. Woodbury is my husband’s uncle. Though he’s now on the opposite coast of us in Canada, I still recall one of the few times we met, one of which was also the first time I ever took the ferry from Vancouver to the island and visited Victoria. Since then we’ve tried to keep in touch, most recently when working on a family tree and again when he published his book Lillian, which was inspired by my husband’s grandmother, who lived to 103. I found the book fascinating. Now W.R. is out with a new novel, Boneyard Highway, and, once again, it’s the type of book you sink into and stay with.

This month’s Indie Corner is the first that features one of my relatives. W.R. Woodbury is my husband’s uncle. Though he’s now on the opposite coast of us in Canada, I still recall one of the few times we met, one of which was also the first time I ever took the ferry from Vancouver to the island and visited Victoria. Since then we’ve tried to keep in touch, most recently when working on a family tree and again when he published his book Lillian, which was inspired by my husband’s grandmother, who lived to 103. I found the book fascinating. Now W.R. is out with a new novel, Boneyard Highway, and, once again, it’s the type of book you sink into and stay with.

One of the first things I ever learned about W.R. is that he is talented at art and, like, me (though I have no skill at visual art), is creative. So, we got along very well in Victoria, soaking up sunshine and wine and having great conversations.

About the Book

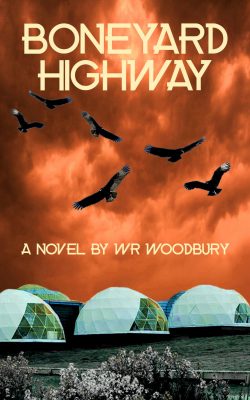

In Boneyard Highway, you’ll find jealousy, murder, intrigue, and a hint of the mythic supernatural at an isolated construction camp in Northern Canada. The world has tipped over the environmental cliff, the skies are orange, and the outside world is disintegrating as the tropics burn and the Arctic ice cap disappears. A work crew is building a new highway to a gold mine because the melting permafrost has destroyed the old road. Doc, the camp medic, is a divorced, struck-off doctor, intent on indulging the many sides of his sexual nature, who uncovers an illicit trade in strange stones that the workers have found during the road excavations. The site of the crystals is a bony-fingered geological anomaly, guarded by an army of vulture-like birds who take offense to the disturbance, spreading fear and panic among the workmen. The diverse and willful crew must unite to survive a flash forest fire and a rash of grisly deaths.

Chat with W.R.

Mary: Let’s talk about some of your previous writing. I read your fairly recent novel Lillian and was so engrossed in it, I stayed up late two nights in a row to finish it. But you’ve been writing novels on and off for forty years. What other novels have you published?

W.R.: Besides Lillian, I have published a book of short stories called The Little Axes of Destiny, and a memoir called Io Vagabondo. Although I have been an occasional diary writer, an inveterate note jotter, and language-obsessed poet, I didn’t start writing fiction until I was 35, got divorced, and left Canada. In the following 15 years I wrote four novels, none of which were published. At the time, before the Internet and mobile phones were invented, I lived and worked in so many countries I had my own page in my friend’s address books. Maintaining connections with agents and publishing houses was difficult.

Mary: I know you to be a creative person as I’ve seen your photography and art, and you’ve also traveled everywhere, which surely enriches your experience. I understand the need to have a creative outlet as well. What are some interesting experiences you’ve had that inspire your art and writing?

W.R.: I have met and worked with many strange and wonderful people, and I often use fictionalized versions of them in my writing. There are as many characters out there as fingerprints, so the well of humanity we have to draw on is almost infinite. Having lived in many places, I believe each has its own spirit, which I do my best to capture. I love art history, painting, and photography, and am fascinated by other artists’ creative process. I believe that one medium informs the other. The more time I spend writing and researching my books, the more I discover that reality is often more bizarre than anything we can invent.

Mary: Your newest novel, Boneyard Highway, just came out this summer. Can you let the readers know what’s happening in the story?

W.R.: Boneyard Highway is about a medic working at a construction camp who discovers that some of the workers have been collecting semi-transparent stones they have found on the jobsite. As he investigates to find out if the stones could be the cause of the strange behaviour in some of his colleagues, he also navigates the aftermath of a failed long-term marriage by proposing sex to anyone who will have him. Camp rules forbid contact but without this, the workers, who risk their life and health every day, are susceptible to a sort of cabin fever, which drives lesser men crazy. To complicate their lives, a forest fire rushes over the camp, adding more bodies to the one the medic had to leave on the road and the other in the freezer.

Mary: It takes place in an isolated construction camp in northern Canada. Had you been to a similar place, or is it an imaginary you created?

W.R.: I worked for the Ministry of Highways for five years and many of our projects required my fellow crew members and I to live in construction camps, if not monthly motel rooms. The location of Boneyard Highway is based on a camp near Chetwynd, a place I lived when the road to the coalfields in Tumbler Ridge was being built. The open pit coalmines were originally developed to fuel polluting steel mills across the Pacific, so we could buy it back as polluting vehicles. It was a government subsidized plan that never paid off and has now been all but shut down, though mountains of coal remain..

Mary: Climate change is central to your novel. The tropics are burning, and the Arctic ice cap is disappearing. I learn sometimes from authors that they didn’t mean to write with concern about climate change (though some intend to do just that). Authors have told me that sometimes it’s just where we’re headed and must be considered when writing. How did you come about having climate disaster as part of your novel?

W.R.: There were a couple years recently, 2018 and 2020, when the summer skies above the west coast of Canada were thick with smoke from forest fires in BC, Washington, and California. The vulnerable had to stay indoors, flights were canceled, roads were closed, and houses burned. I wondered if this was how the world would be in the future, that we might never see blue skies again, that crops would fail, that tribal violence would break out in the cities, and that an isolated camp in the north might be the safest place to be, though nowhere in the world would escape the effects of worsening air quality. We might not be able to breathe outdoors without a filter and supplementary oxygen.

Mary: There’s a supernatural element to your story with mythical stones that are guarded by strange birds. These crystals are part of an underground trade, which is where mystery and even some horror comes in. I love stories with magical or mysterious substances—like Dune and Black Panther. How did you come up with the idea for these stones?

W.R.: The medic discovers that the crystals the workers have been collecting are radioactive, and at the location on the site where they are most dense, they appear to be guarded by vultures who protect the stones as if for some future event. The idea of a mineral having unusual properties was suggested by the search for rare earth elements that are needed for much of our modern technology. The crystals I have named in the book contain thorium, which can be used to make safer nuclear reactors than our current uranium ones. Uranium reactors were chosen for development over thorium because uranium can be more easily weaponized.

Mary: The crew is diverse and determined; what inspired you to create these particular characters? Do you think, in the face of disaster, people do usually unite to survive and fight together?

W.R.: A construction camp, like any workplace, can be a mix of all sorts of people, each with their own lives outside of camp. For most, the unifying factor for their presence is money, but they know their colleagues well enough to identify the panickers and dividers from the calm and steady ones. The majority understand that staying strong together is their best defence. Although there are jealousies, struggles for power, and internal friction in any group, the sexual tension and conflict is closer to the surface in a contained environment like a camp. I felt that having a range of races and sexual orientations would represent as much of humanity as possible since we all share the same struggles with outside forces.

Mary: Anything else that you want to add?

W.R.: I have heard it said that my generation, the baby boomers, are responsible for the state of the climate, but I don’t accept this. A millennial is just as prey to over-consumption as a boomer. As a way of defending my part of the post-war generation, I wrote a book called Small World, which documented the unassuming and temporary places I have lived, from boathouses, to garden sheds, construction camp trailers, work sponsored motel rooms, abandoned ranch buildings, and one-room traditional village houses, none of which were the presumed sprawling home with a pool in the suburbs. This book was ultimately absorbed into the memoir Io Vagabondo.

Also, as a change of pace, this year I finished writing a crime mystery set in Vancouver in the mid 1970’s, called Lotusland. The book is not out yet, but may be in early next year, depending on publisher decisions. I am currently working on another book of short stories.

Mary: Thank you so much, W.R. We’ll talk again about future books!

Author Bio

W.R. Woodbury was born and raised in British Columbia. He has lived and worked in places like Kaslo, Revelstoke, Chetwynd, Prince George, Terrace, Alexis Creek, Kamloops, and Vancouver, before spending decades away from Canada in Greece, Italy, France, Germany, England, and Australia. When he returned to Canada permanently, he set aside novel writing and made forays into painting and photography while working his way up to being a hotel manager. He has also worked as a librarian, forest-fire fighter, highway surveyor, banker, tour guide, night auditor, taxi driver, landscaper, postman, ranch hand, stained glass artisan, draftsman, and courier driver. Now retired, he resumed writing fiction in 2018.

W.R. Woodbury was born and raised in British Columbia. He has lived and worked in places like Kaslo, Revelstoke, Chetwynd, Prince George, Terrace, Alexis Creek, Kamloops, and Vancouver, before spending decades away from Canada in Greece, Italy, France, Germany, England, and Australia. When he returned to Canada permanently, he set aside novel writing and made forays into painting and photography while working his way up to being a hotel manager. He has also worked as a librarian, forest-fire fighter, highway surveyor, banker, tour guide, night auditor, taxi driver, landscaper, postman, ranch hand, stained glass artisan, draftsman, and courier driver. Now retired, he resumed writing fiction in 2018.