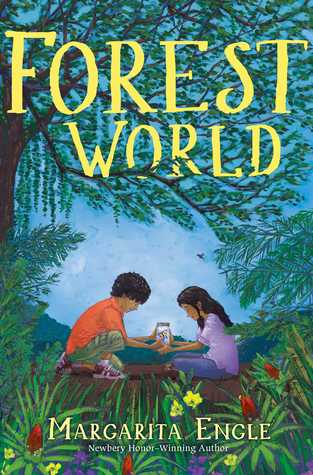

Middle Grade Fiction

Reviewed by Kimberly Christensen

Edver and his mother left Cuba when he was just a baby. His father stayed behind and Edver hasn’t seen him since. But when relations between the United States and Cuba finally permit unrestricted travel between the two countries, Edver’s mom sends him to Cuba to spend the summer getting to know his dad–and the surprise older sister that Edver never knew about who stayed behind with their father when their parents split up.

Edver and his mother left Cuba when he was just a baby. His father stayed behind and Edver hasn’t seen him since. But when relations between the United States and Cuba finally permit unrestricted travel between the two countries, Edver’s mom sends him to Cuba to spend the summer getting to know his dad–and the surprise older sister that Edver never knew about who stayed behind with their father when their parents split up.

Luza has lived her whole life in Cuba, wondering what became of her mother and brother. Food and necessities in Cuba are rationed and Luza has had to make do without many material things, so when she meets her brother, she finds him indulged. Between that and the fact that their mother “chose” him, Luza resents his presence even as she wants to ask him a million questions.

Edver is lost at first, without the internet and the comforts of home. He feels uncertain about how to relate to his new family members and has his own issues with his constantly traveling mother, for whom saving species from extinction seems more important than caring for her own children. Soon he finds a place with his father, patrolling the rainforest to keep poachers away from the endangered plants and animals.

As Edver and Luza begin to form a relationship, they devise a plan that they think will convince their mother to return to Cuba so that Luza can finally see her. But when they post a sighting of a rare butterfly, they accidentally attract the wrong sort of attention. A poacher called “The Human Vacuum Cleaner” shows up in their forest and tries to hire the siblings to help him collect the butterfly. Instead they devise a plan for netting the bad guy and saving species from extinction just like their parents.

Forest World is a story told in verse from two alternating perspectives, those of Edver and Luza. From Edver, the reader learns about the life of Cuban immigrants in the United States and about the children’s mother. From Luza, the reader delves into the stresses and joys of living in a closed country and sees the strength of the bonds between the family members who stayed behind in Cuba.

Watching the children try to sort out their complicated family history is painful at times. The children’s mother is not sympathetic at all, and it is difficult not to feel resentful of her near-complete ignoring of the children’s emotional needs. The possibility that the mother is autistic (described here as a “genius” who is single-minded about her work) feels like a cheap way to both discredit her passion for her work and to explain why she is so bad at caring for the feelings of others. The fact that she barely makes an appearance in the book leads her character–which is a central one in the minds of the children – to be highly unsatisfying. It is never clear whether she understands the damage she has done to her children, only that the silence she has maintained has harmed them both.

The children’s mutual love of animals and their passion for ecology carries the book. Through their adventures, the reader learns about Lazarus species – animals which are thought to be extinct and then which are rediscovered–and about efforts to keep those animals from becoming truly extinct. Several issues around poaching are discussed, with a focus on how collectors fuel the problem. The children’s commitment to disrupting such practices feels very real and contemporary children would have an easy time connecting with their passion.

The author’s writing style and her use of verse to tell the story kept me as a reader from fully immersing myself in the plot and character. I felt like I was being kept at arm’s length from the emotion of the story, and that none of the story lines went deep. For me, it lacked emotional resonance. Even though I appreciated learning more about Cuban-American relations and Lazarus species, I didn’t connect with the story and therefore only give it 3 of 5 stars. That being said, I could see this book being useful in an educational setting because of the breadth of conservation issues it raises and the fact that it isn’t long or overly complex, which would make it accessible to readers on the younger end of middle grade.