Click here to return to the series

Welcome to Dragonfly’s new global eco-fiction series, where I explore fiction from around the world dealing with environmental crises. In this feature, I look at, and re-enjoy, Agam, a book project from the Philippines in 2014.

Thanks very much to Redentor Constantino, from the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities–publisher of the book Agam: Filipino Narratives on Uncertainty and Climate Change–for permissions to excerpt the cover and other information about the book, and for providing assistance in finding out more about this amazing title. Blockquotes are text from the Agam website.

Agam reflects the confrontation between climate change and diverse cultures across the Philippines. It combines original new works in prose, verse, and photographs and depicts uncertainty—and tenacity—from the Filipino perspective, minus the crutch of jargon.

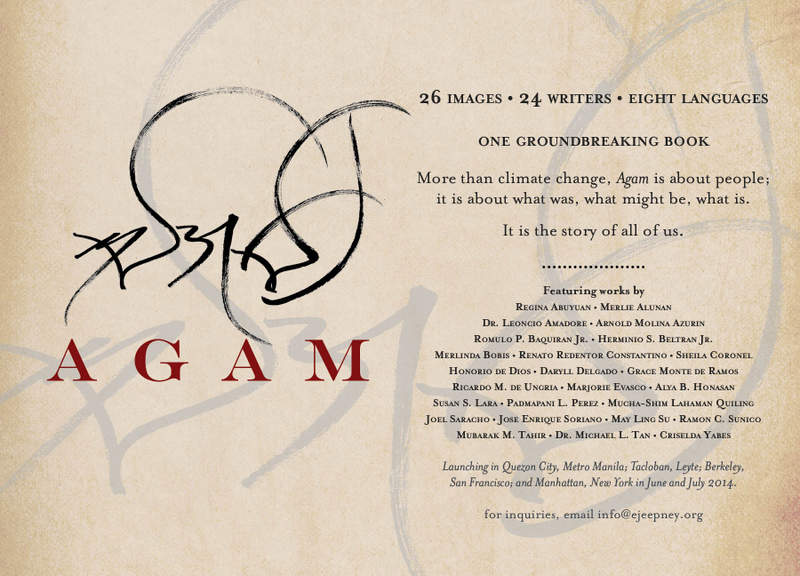

The title, Agam—an old Filipino word for uncertainty and memory—captures the essence of this groundbreaking work. Inside are 26 images and creative narratives in eight Filipino languages (translated into English), crafted by 24 writers representing a broad array of disciplines—poets, journalists, anthropologists, scientists, and artists.

All proceeds from the sale of Agam will go to the project Re-Charge Tacloban, an integrated solar and sustainable transport services and learning facility in Tacloban, a city devastated by Typhoon Yolanda (international name: Haiyan), the strongest storm ever recorded at landfall.

I have recently been in touch with Renato again, who stated:

Agam has been launched in several capitals. Apart from a huge number of events in the Philippines, Agam has been launched as well in Washington DC, Manhattan, Berkeley, Denver, Berlin, and Bonn. The book has won three national book awards. For two years now we have partnered with Iyas, an annual creative writing workshop run by some of Agam‘s contributors. We have helped organise activities as well as provided lectures and insights into the climate issue and the way it intersects with the creative process. We are working on an international version now, helping put some shape into the overall scope of the book.

He also stated wisely:

Get your bearings, lose your marbles, this might very well be the basic principle by which advocacy and literature will meld in the face of the climate crisis. I can’t think of a period in history when poets and writers are more needed than the present. This is our Thermopylae, our defining moment; we are faced by change that will only become even more violent the longer the spectatorship of the public remains ascendant. We face likewise the opportunity to survive and thrive and, most importantly, to sweep aside vestiges of the old order constructed by anthropomorphic conceits thinking we, particularly the few, can live so large and so indifferently without any consequences.

Agam is a song, a poem, a story, a photograph, a calligraphic sweep of the hand. It is all of these and more. One of its descriptions: This is a book that asks you to sit down and take a deep breath, it draws a line in the sand and whispers in your ear, “This is where our stories begin.” It tells of the archipelagic country’s people and natural landscapes and environmental changes. It roars with the wind carving through coconut groves and buildings. It swims with the rising Abra River, it counts fingers from the past while observing the many storms. It eyes the haunted wreckage from typhoons and floods. It follows the uprooting of trees, the remaining dust. Naomi Klein said of the book:

Agam is exquisite: a deeply original concept executed with tremendous artistry. Rather than asking readers to care about the whole world at once, these elegant vignettes distill the climate crisis down to its most intimate and human details. By focusing on the small, the biggest questions of all are cracked open. How do we heal after our most beloved and nourishing places have turned against us? How do we live in a world that has itself become a question mark? And most of all: How can we stop inflicting such violence on one another?

This glance into the dwindling wildness of the Philippines is told beautifully, thoughtfully, and with an eye to how humanity is impacted. According to Ecowatch:

The Global Climate Risk Index 2015 listed the Philippines as the number one most affected country by climate change, using 2013’s data. This is, in part, due to its geography. The Philippines is located in the western Pacific Ocean, surrounded by naturally warm waters that will likely get even warmer as average sea-surface temperatures continue to rise.

The Stories Within

The stories in Agam are accompanied with beautiful artwork and photography. These people are not fictional. The storms are not fictional. Agam fuses storytelling and reality in an artistic medium.

In “Tulo Ka Hinumdoman,” Merlie Alunan writes poetically of the strength of wind and how it slashes through groves of banana and coconut trees and rice fields, how the same wind could be so strong as to turn a person into dust, how the wind ruins buildings and urban objects, how it–with the rising seas–takes what’s in its path. There’s an overwhelming sense of nature being boiled up by climate change, and turning more powerful.

In “Agayayos” (Ever Flowing), Arnold Molina Azurin recalls a former town being entirely moved to higher ground away from the Abra River as wild waters rose and rose. He says this constant environmental and climate shifting: “Sometimes very slow in coming and almost imperceptible, but sometimes severely and instantly catastrophic.” Landmarks end and new ones begin–sometimes so subtly, sometimes strongly–always forever changing.

Merlinda Bobis, in “Sampulong Guramoy” (Ten Fingers), asks us to see the invisible. Ten fingers of the mother…of the father. How many times does one count when rotten rice needs to be scavenged from a storm, when a roof needs fixing, when the village is evacuated. I can see a child using the fingers to count and see the shadows and light dash to and fro in these terrible storms, which become haunting memories. Over and over.

In “Unnatural Disasters,” Sheila Coronel finds power in the bayanihan spirit, as the compassionate people help each other through each crisis. According to TheMixedCulture.com: The Bayanihan (pronounced as buy-uh-nee-hun) is a Filipino custom derived from a Filipino word “bayan”, which means nation, town or community. The term bayanihan itself literally means “being in a bayan”, which refers to the spirit of communal unity, work, and cooperation to achieve a particular goal.

In “Sa Laylayan ng Bahaghari,” Ni Honorio Bartolome de Dios tells the story of a beach that is now gone, swallowed by the sea. As with the other stories, the tale is haunting and reminiscent of loss and death. But there is still hope. Maybe a rainbow will come.

May Ling Su, in “The Power Couple,” shows the spirit and strength of Filipino people–and hints at the disparate contribution to climate change vs. the uneven results. The power couple recycles. They do not do social media. They have no education, money, or opportunities. They do what they can to survive and live in the culture–fishing, hunting, toiling in extreme weather. They are hit hard by climate change:

We’re called “resilient” by the system that ravages our resources and spits us out, the remains of the carcass they have consumed and now consider waste.

Authors

Agam‘s authors are Regina Abuyuan (also the Executive Editor), Merlie Alunan, Dr. Leoncio Amadore, Arnold Azurin, Romulo P. Baquiran Jr., Herminio S. Beltran Jr., Merlinda Bobis, Renato Redentor Constantino, Sheila Coronel, Honorio de Dios, Daryll Delgado, Grace Monte de Ramos, Ricardo M. de Ungria, Marjorie Evasco, Alya B. Honosan, Susan S. Lara, Padmapani L. Perez, Mucha-Shim Lahaman Quiling, Joel Saracho, Jose Enrique Soriano, May Ling Su, Ramon C. Sunico, Mubarak M. Tahir, Dr. Michael L. Tan, and Criselda Yabes.Among these authors are winners of the Carlos Palanca award, a Magsaysay Awardee, a SEAWrite Awardee, the Chancellor of the University of the Philippines-Diliman, public intellectuals, and pop culture experts. All of them in one book.

Click here for bios of Agam‘s authors.

The Photographer

Behind the lens is Jose Enrique Soriano, who took portraits of people he met. He imposed no story or caption behind their faces—no unnecessary drama, just “the people at the forefront of climate change.” In this case, it means those who live with its effects. There is no sweeping background of the devastation. The pictures are about the people, as the stories are too.

The Cover

The cover is a mix of new and old typography by Kristian Kabuay. It’s not very apparent, but the calligraphy is baybayin with modern techniques from the Hanunuo Mangyan tribe in Mindoro. (The black “squiggles” on the front cover reads “A-Ga-M” and on the back, the more traditional “A-Ga” is written.)

Please be sure to read the 10 Reasons Why We Love Agam.

For more information about ordering, please visit Agam’s Facebook page.

The featured image is by Dee Rexter, titled Boat from Bora, taken at Boracay Island Malay, Aklan. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Some content previously published at Eco-fiction.com.

Pingback:To resist, and to win, it’s time we tell our stories - Agam Agenda