Click here to return to the world eco-fiction series

About the Book

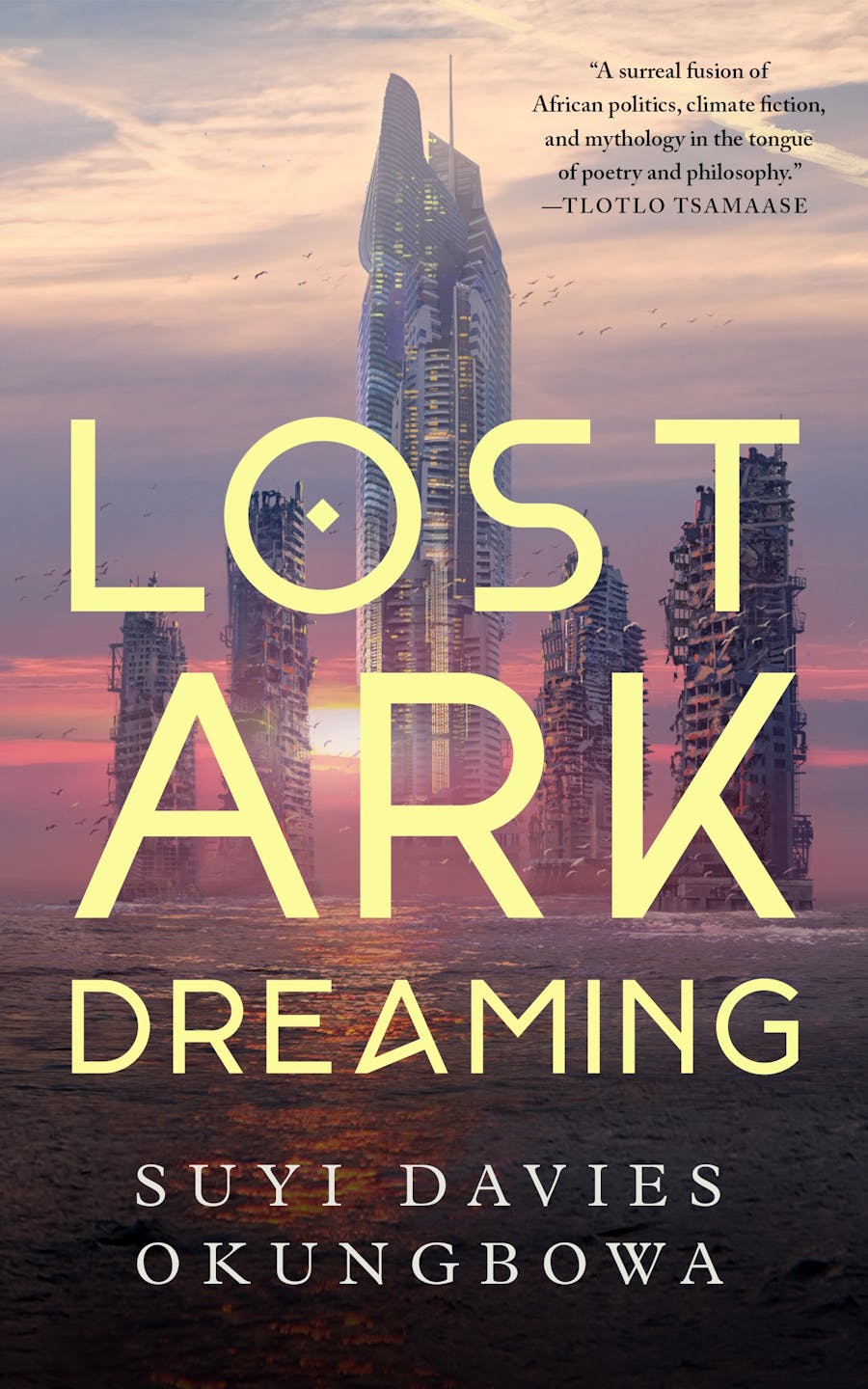

Lost Ark Dreaming is out May 21, 2024: Macmillan Publishers/Tordotcom.

The brutally engineered class divisions of Snowpiercer meet Rivers Solomon’s The Deep in this high-octane post-climate disaster novella by Nommo Award-winning author Suyi Davies Okungbowa.

Off the coast of West Africa, decades after the dangerous rise of the Atlantic Ocean, the region’s survivors live inside five partially submerged, kilometers-high towers originally created as a playground for the wealthy. Now the towers’ most affluent rule from their lofty perch at the top while the rest are crammed into the dark, fetid floors below sea level.

There are also those who were left for dead in the Atlantic, only to be reawakened by an ancient power, and who seek vengeance on those who offered them up to the waves.

Three lives within the towers are pulled to the fore of this conflict: Yekini, an earnest, mid-level rookie analyst; Tuoyo, an undersea mechanic mourning a tremendous loss; and Ngozi, an egotistical bureaucrat from the highest levels of governance. They will need to work together if there is to be any hope of a future that is worth living—for everyone.

Chat with the Author

Mary: Hi Suyi! Thanks for the interview. Can you introduce yourself and tell us about your background?

Suyi: I grew up in Benin City, Nigeria, where I was born and lived until after university. I worked in multiple cities around the country, Lagos included—I lived there until 2018. I’ve since moved abroad, finishing my grad degree in the US and moving to Canada for a job as a creative writing professor. Prior to this, I swung between fields—my bachelor’s was in civil engineering, and I did some work in bridge construction and structures; later, I worked in consulting, then in marketing communications and graphic design, then in nonprofit program management, etc. My creative work tends to move in the same migratory patterns and pull from all over the map in the same manner that my life has.

Mary: What makes you love science fiction and fantasy, and what can those genres tell us about our world today?

Suyi: I like speculative work across the spectrum—science fiction, fantasy, horror, surrealism, what have you—for the stark relief into which it throws what may seem an otherwise mundane or everyday concern. Some matters and concerns, through repetition—and therefore dilution—tend to lose the power to provoke a response from us. Speculative fiction takes that matter away from the (noisy, overcrowded) familiar environment, and throws it against something stark, unfamiliar, to great effect. The very matter we’ve considered and discussed all this time—say, climate change—we suddenly see in new light, shined upon from a different angle, forcing us to reimagine, and therefore reconsider.

Mary: What writers and novels did you enjoy while growing up?

Suyi: My parents were not fiction readers, per se, but our bookshelves were stocked with everything from religious texts to mythologies to encyclopedias to children’s books to crime novels to ‘60s & ‘70s African novels. I read everything in the average ‘90s middle-class Nigerian kid’s library—Enid Blyton, Goosebumps, Dickens, Mills & Boons romances—before segueing into The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born and The Godfather. I didn’t really fixate on specific authors until I was an adult, but I do remember certain books staying with me—the locked-room-style British detective novels that came after Conan Doyle; the Nigerian Pacesetter series of fast-paced urban novels and their counterpart “Onitsha market literature”; the anti-apartheid novels of Peter Abrahams, like Mine Boy; ‘80s and ‘90s Nigerian authors like Chukwuemeka Ike and Cyprian Ekwensi. Later in adulthood, when I started thinking of writing speculative work, I encountered writers like Neil Gaiman, Octavia Butler (who I only discovered in 2015 or so) and Nalo Hopkinson, whose works I’ve since continued to enjoy.

Mary: Sounds similar to my parents’ library. I’m looking forward to Lost Ark Dreaming. It’s been a while since I’ve read a good climate change story. I think it would be interesting to our readers about what led you to write this story.

Suyi: During my years living and working in Lagos, I became quite attuned to the precariousness of living so close to the coast. Much attention is often paid to Lagos as a cultural and commercial hub, but I believe its physical and geographical concerns shape the city’s viable futures—economic and otherwise–than many realise. So when the Eko Atlantic Towers—the real-life towers on which the Fingers in Lost Ark Dreaming are based—began to be constructed, it struck a chord with me. I didn’t think I was going to write about the towers at all—I was simply concerned with the conditions that sparked the need for such a set of towers to be built on a reclaimed island off the coast.

Mary: The story is set in Nigeria after the Atlantic Ocean has risen. What other ecological changes are affecting near-future Lagos?

Suyi: Increased rainfall, intense flooding, heat waves—the same stuff we’re seeing all over the globe. Perhaps because these haven’t turned up to devastating levels yet—or perhaps because we’ve become so used to disaster and devastation now being the everyday—we’re unlikely to hear about this in the news. These towers represent, in my opinion, all of Lagos’s environmental concerns coming together. The coastline’s natural and human-made recession; the enforced displacement of waterside communities; the history of violence on this same Atlantic, going all the way back to trans-Atlantic slavery; the hypercapitalist ventures, towers included, that trigger all these effects and movements, impacting both people and environment.

Mary: The story is told in the perspectives of three main characters. Rebecca Roanhorse said, “It’s a quick read with novel-sized tension and action and some lovely high concept ideas about immigration, class, and community.” Can you describe the tensions among the main characters?

Suyi: I used to drive past the gates where the workers tasked with building these towers were stopped and checked—like immigration—before being allowed on site. That sole event made me realize that in the event that these towers became some sort of refuge, residents would likely be split along these same lines. Those who owned the towers and made the decisions, those forced to work under challenging conditions to keep the towers running, and those used as buffers, to keep this chasm open and ensure it never fully closes. It made sense, therefore, to have characters who give us windows into the thinking and motivations of these differing peoples. But more importantly, for us to recognize that the factors that shape our decision-making in these conditions are multifold and complex, and ultimately are much closer to home than we think.

Mary: I like how Nigerian mythos enters into the story. Can you describe it without spoiling the novella?

Suyi: I think of it as an investment in cosmology. Humans have historically found ways to tell stories about our origins, and I wanted to consider this big moment of change an opportunity to rewrite who we think we are, merging aspects of who we’ve been with who we could be if we let our imaginations run wild. In this case, I’m piggybacking off of Yoruba cosmology, working with the ocean deity, Yemoja, while weaving in aspects of other popular flood and sea mythos like Atlantis or ancient stories of great floods or literature that reimagines a undersea civilizations, like Rivers Solomon’s The Deep. What we end up with is an amalgam that becomes its own cosmology of the towers in Lost Ark Dreaming.

Mary: Would you like to add anything else?

Suyi: It would be a failure of storytelling to frame environmental futures solely as a matter of systems, of science and geology and atmospheric conditions intertwining. We must realise that such futures are about people and the conditions into which we are forced. Lost Ark Dreaming, at its core, is about that. Refusing to accept the realities before us—perhaps, wrongly, or perhaps buttressed by access and privilege—is often due to the belief that whatever new conditions arise, we will surmount. But we must remember that the whole world doesn’t need to burn for us to be scalded. Every small corner of the world has people with hopes and dreams and reasons to live. A little burn, a little drowning, even in some faraway place, is a mark on us all.

Mary: I agree wholeheartedly. Eco-fiction is about the connections and experiences that humans have with the natural world and all its changes, good and bad. I so appreciate your time and am looking forward to the book arriving at my doorstep!

About the Author

Suyi Davies Okungbowa is an award-winning author of fantasy, science fiction, and general speculative fiction. He has published various novels for adults, the latest of which are Warrior of the Wind and Son of the Storm—both of The Nameless Republic epic fantasy trilogy—and the novella, Lost Ark Dreaming. His debut novel, David Mogo, Godhunter, won the 2020 Nommo Award for Best Novel.

Writing as Suyi Davies, he has also published works for younger audiences, such as Stranger Things: Lucas on the Line (Random House Kids, 2022) and Minecraft: The Haven Trials (Del Rey, 2021), and contributed to the instant #1 NYT bestselling anthology Black Boy Joy (Delacorte, 2020). His shorter works have appeared in various periodicals and anthologies, and have been nominated for various awards.

Okungbowa is an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at the University of Ottawa in Ontario, where he currently lives. As a speaker and instructor, he has taught writing at the college level and spoken at various venues, institutionally and publicly. He earned his MFA in Creative Writing at the University of Arizona.

You can find him online @suyidavies everywhere, or via his newsletter, SuyiAfterFive.com.