Click here to return to the series

Update: The English translation of Rokit, Before the Rocket, is published by Praspar Press. You can order from here https://www.londonreviewbookshop.co.uk/stock/before-the-rocket-loranne-vella. They ship worldwide.

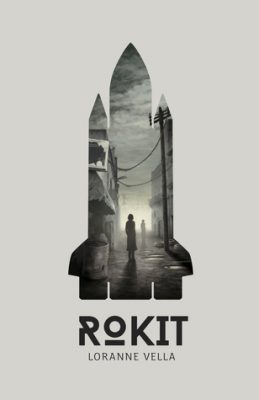

Today we travel to Malta with Loranne Vella to discuss her award-winning novel Rokit (Merlin Publishers, 2017).

Today we travel to Malta with Loranne Vella to discuss her award-winning novel Rokit (Merlin Publishers, 2017).

It’s 2064, and the European continent is disintegrating: walls are up, and communication structures are down. A car crash in Croatia leaves Rika Dimech, world famous fractal photographer, dead. Her 21-year old nephew, Petrel Dimech, the war photographer, decides to travel by sea to Rika’s country of origin, Malta, now occupied by the Italian regime for the purposes of space exploration. He intends to spend two weeks in Malta to find the remains of Rika’s past. Twenty-three years later he is still there looking for clues about his own roots. Employed as a photographer at the space centre for most of this time, Petrel discovers not only Rika’s past, but also his own future. In his inability to move around spatially (the island is divided into sectors, each heavily guarded), Petrel discovers a way of moving in time. His son Benjamin is one of the main revolutionary figures fighting for Malta’s freedom. Petrel who prefers to look at the world through his camera lens, is caught up in a different kind of revolution – a time-loop which links his future to his past to his future. Rokit is a story about time, space, photography, roots, geometry, revolution and ultimately hope. The rocket, itself a symbol of hope, is forever present in the background of these events.

Following is my chat with Loranne. I was honored to talk with her about this magnificent novel.

Mary: Rokit takes place in a climate-changed, dystopian future. But there’s much more here than cliched tropes. This is a genre-bending novel that is speculative but also realistic and literary, with the unique concept of the elusive perspective of photography and how a rocket can propel someone to a further distance where a fuller picture is more clearly seen. I’ll get into some of the perspective talk later, but for now wondered if you took the route of fiction to partially expose our world now, the hyperobject of climate change, and how we cannot take a still photo of it and find focus–that we have to widen our perspective?

Loranne: Yes, definitely, because stories have a way of driving the message home more than any headline news, at least that’s always been the case for me. Rokit is my way of commenting about what is happening in the world today. It’s a cautionary tale, if you will: if we persist in what we’re doing now, this might be the result in half a century’s time. One possible result, of course, there could be many others. But this is the image of the future that I wanted to present, to explore. The comments are there, between the lines, whispered or hinted at by the characters, at times spelled out. Climate change is both the backdrop of this story as well as the driving force of the plot–things would have happened very differently had there been no tsunamis and heavy rains ravaging this little island in the middle of the Mediterranean in 2064.

However, there are other ways of looking at this story, depending on which angle we look at it from, or which detail we decide to focus upon. It’s about photography but also about space and time. It’s about geometry (circularity versus linearity) as much as it is about physics (light, shadows, darkness). It’s about a revolution in all the possible senses of the word. It’s been described as a coming-of-age novel where the teenage Benjamin discovers he has an important role to play in liberating his country. It’s about the search for one’s roots, one’s identity and purpose in life.

Mary: What is the reality of the island of Malta and the rest of Europe in 50 years according to Albert?

Loranne: I created this image of the future of Europe and Malta by asking a basic question: what if we’re actually moving toward a future where we lose, or even give up voluntarily, the very things we hold so dear today? Democracy, a unified continent, independence, telecommunications, freedom of movement, freedom in general. What if we will actually dismantle all we’ve been building this past century to reinstate that which we spent decades striving to liberate ourselves from; what if we will once again opt for borders to open territories? What if we were to find comfort, once again, in isolation? Albert Cauchi, the fictitious historian in the novel, comments in detail about this phenomenon is his work titled “Min jibni u min iħott” (“Those that are busy building, and those that are busy dismantling”). History, according to Cauchi, proves that time moves in circles, spirals even, and that man is bound to repeat past mistakes, making them even grander next time round.

And Malta, in 50 years’ time, will once again lose its independence (2064 would commemorate 100 years since the island gained its independence from the British Empire). In a time when the island is slowly succumbing to the wild sea and crumbling at the edges, the Italian regime lends a seemingly helping hand and lures the islanders into accepting its harsh terms. The island of Malta has no choice but to accept. Malta falls once again under foreign rule (history repeating itself once again), and slowly starts being evacuated. This results in an underpopulated Malta (the other extreme of the reality today), where the islanders have to escape their country and seek refuge some place else; here is where I have created another inversion in order to make a comment about the intolerant approach some Maltese people have towards refugees and migrants who regularly arrive on our island seeking refuge. Under the Italian regime, the few thousands of Maltese who remain on the island are segregated into sectors, thereby making the size of the island even smaller. Eventually a group of these are transferred to shelters underground, where everything becomes unbearably small and dark.

Mary: I am mesmerized by the concept of illusion, or maybe more succinctly the photographs that lack shadows or that were taken shortly before someone died. Or photos that are slightly out of focus, or where a person was always trying to be in the center. Can you talk some about this and how the science fiction film La Jetée played into it?

Loranne: It was important for me to introduce the world of Rokit to the reader as a fictitious one, as a world where the rules of physics do not fully apply. It is for this reason that right from the start we encounter little details that seem to belong to a world other than our own. But I was not interested in high fantasy or science fiction. Just a slight distortion of the world we know. Because this will help us to imagine another world, very similar to ours, but not quite. It’s like tilting one’s head to get a better view of what’s in front of us. I’ve always had this idea of fiction, which is why I am particularly fond of literary works that flirt with the fantastical or science fiction but are not outrightly so. It is all an illusion that distorts and yet reveals what would otherwise remain hidden. Much like the way photography works. Rokit makes heavy use of the principles of photography, in form as well as in content. The main character is a photographer. His son, having lived his entire life in captivity in one single village on this small island, has a limited sense of perspective. To bring about the revolution that could lead to the liberation from the tyrannical Italian regime, the son has to learn about the history of photography–about light, detail, perspective, focus–from his father.

Chris Marker’s La Jetée has been a major influence in my work, not only when I was writing Rokit, but also with my previous novel MagnaTM Mater, mainly because of my fascination with the idea that the future can hold a solution to the crises of the present. And that only by travelling in time can we hope to find the answer to our problems. In MagnaTM Mater, the 15-year old Elizabeth writes a short story about a woman, V (who is no other than her own mother Veronica), who travels to the future to bring back home an answer to all our problems that are a direct result of climate change. In Rokit this idea is taken up again–also because both Elizabeth and Veronica reappear in Rokit–this time round not to tackle the problem of climate change but in order to bring about the revolution that will set the islanders free from their oppressors. Some characters do travel in time in Rokit. However, the novel is not about travelling in time. Rather, it’s an exploration of what would happen if that kind of temporal jump were a possibility, as well as an enquiry into whether time is linear, circular, spiral or other.

Mary: I find all this fascinating. You introduce many central metaphors and other concepts in this novel: the maze, the minotaur, the cathedral. Care to elaborate on any of these ideas?

Loranne: Petrel perceives the world around him in conceptual terms: geometry–he tends to see everything, both objects and ideas, in terms of lines, circles or spirals; Greek mythology, when he ends up in an underground shelter he cannot but make the connection with the minotaur’s maze; he compares himself to Perseus, holding the head of the Medusa to represent the role of the war photographer as he captures images of atrocity to present them to those who are not aware that it exists; and Veronica to Calypso (she seduces Petrel to keep him from leaving the island) and to the shape-shifting Proteus; he sees Italy’s coming to Malta’s aid as a Trojan horse to conquer the island. Petrel’s associations are always grandiose. The underground shelter reminds him too of the bizarre masterpieces of the great visionaries such as Piranesi, Gaudì or Escher.

On the other hand, Benjamin is also being exposed to grand concepts in order to help him make sense of the limited reality he is trapped in. His “teacher”, Mirelle, uses quotations from philosophical and literary works to help the young generation born in captivity to imagine a world much greater and more significant than the one they know. She is the one who compares the coming revolution to a cathedral. The foundation of the cathedral lies in the past, in the revolutions that have taken place decades and centuries before; the building itself represents the present, the daily actions that each one of them take in order to bring about the eventual downfall of the oppressor; the bell, then, will chime victory in the future. The image of the chiming bell haunts Benjamin because his greatest fear is that, no matter how much he fights for the island’s liberation, he will no longer be there to hear the bell chime. The only way he can be present to hear it is to make a leap in time.

Mary: What are your overall thoughts on the way the destruction of the natural world is handled in fiction, and do you have any favorite authors that made you think more about it?

Loranne: It seems to me that stories–written these past 30 years, at least–which are set in the future, tend to tackle, directly or indirectly, the consequences of climate change. One of my favourite authors, David Mitchell, sets the last section of The Bone Clocks in 2043, where natural disasters have resulted in a depletion of resources. This last chapter is perhaps one of the most touching endings I have ever read. Yoko Tawada, in The Last Children of Tokyo, presents a devastated Japan one hundred years from now. We are confronted with an unlivable Tokyo where water, air and soil are so heavily polluted as to be poisonous. What we take so much for granted in our everyday life –the air we breathe, the water we drink, the land we cultivate–is that which usually becomes scarce in dystopian literature.

Mary: Thanks so much, Loranne. I can’t wait to share your thoughts and the novel Rokit with Dragonfly’s readers!

Loranne also linked me to an article from the Times of Malta, which describes what effects global warming has already had, and will continue to have, on the small island of Malta in the Mediterranean Sea, just south of the Italy’s southern tip. The article says that in the next thirty years, the island could become an “arid, thirsty, overheated rock.”

Moreover, “the predicted sea level rise could transform the landscape and affect buildings that are close to the sea in low-lying areas”, an impact which “would be further compounded by strong winds and storm surges battering the coast.”

Loranne said that in Rokit, similarly, are crazy weather conditions and the Sirocco wind.

About the Author

Loranne Vella is a Maltese writer, translator and performer. Between 2007-2009 she co-wrote the three volumes of the Fiddien Trilogy with Simon Bartolo, novels which shattered all sales records in the field of literature for children and young adults and are still widely read. Each of the three volumes won the National Book Prize, and are currently being translated into Spanish. In 2012, Vella’s novel MagnaTM Mater won 2nd prize in the category for young adults. Rokit, her latest novel, is her first novel for adults. It was published to critical and public acclaim in March 2017 and won the National Book Prize in 2018. It is currently being translated into English. Vella has translated several books for children, two of which won the Terramaxka National Children’s Books Prize in 2015 and 2016. She lives in Brussels, where she also directs the interdisciplinary performance art group Barumbara Collective. Their latest performance–Verbi: mill-bieb ‘il ġewwa–was based on Vella’s collection of short stories take a look inside (me), which is due for publication later this year.

It is not listed on Amazon, either in the US or the UK. I suspect shipping from Malta to the US would be prohibitive. Will the novel eventually be listed on Amazon?

Hi Robert,

Unfortunately I do not know the ongoing publication status of books posted here. Maybe you can research who the current publisher is and ask them.

The English translation of Rokit, Before the Rocket, is published by Praspar Press. You can order from here https://www.londonreviewbookshop.co.uk/stock/before-the-rocket-loranne-vella

they ship worldwide.

thank you