Click here to return to the series

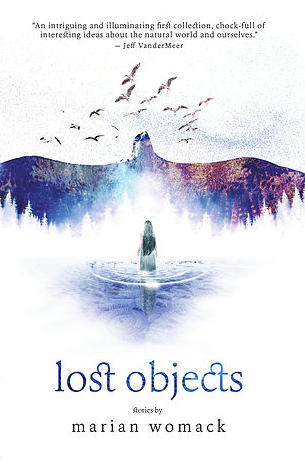

Over the summer, I spotlighted author Marian Womack’s new collection of short stories, Lost Objects. These stories explore place and landscape at different stages of decay, positioning them as fighting grounds for death and renewal. From dystopian Andalusia to Scotland or the Norfolk countryside, they bring together monstrous insects, ghostly lovers, soon-to-be extinct species, unexpected birds, and interstellar explorers, to form a coherent narrative about loss and absence. Marian explained to me that these stories were written over a period of several years and reflected various perspectives on similar issues–which, to me, presents an opportunity for examining world eco-literature. Lost Objects is connected to her own travel, including to Cambridge, UK; north of Inverness in Scotland; Barcelona, Spain; and other areas she traveled as a youth. She stated that the stories are not just speculative–they describe plausible extrapolations of the current world. She also noted that she believes science fiction is not really about the future but about the present as we experience it.  Though I would recommend the entire collection for excellent and thoughtful reading, especially if you enjoy ecological weird fiction, this month, in part VI of the series, we travel to Andalusia, where Marian’s short story “Little Red Drops” takes place.

Though I would recommend the entire collection for excellent and thoughtful reading, especially if you enjoy ecological weird fiction, this month, in part VI of the series, we travel to Andalusia, where Marian’s short story “Little Red Drops” takes place.

The tale is a modern day version of “Little Red Riding Hood,” set in a dystopian world. Similar to the historical fable, this story is magical and mysterious but offers the same practical lessons: beware of wolves dressed in disguise, mind the woods, and take care to stay on the path. While images of blood, girls in red capes, wolves, and a forest to stay away from loop into the story, the lost objects comprise of innocence and ecological surroundings.

In the story, a woman rents a cottage near an Andalusian forest after having gone through a crisis, in which she was treated badly by an ex. She lands here after receiving a premonition from a fortune teller that a life would have to be taken–a rabbit, in this case. Andalusia, in southern Spain, is an autonomous community just north of the Straight of Gibraltar and the Mediterranean Sea. Its normal temperatures are very hot in the summer (up to 40C/104F) and mild in the winter (an average of 10C/50F). In Marian’s story, however, a snow event is happening, which colors a run-down nearly abandoned village with the light and shadow of winter. We get hints of this event happening after an older or different world, when things began unraveling environmentally. The forest nearby is not your grand forest of yore but mere copses of trees–as a woodcutter man with a dog, who brings her wood and water, explains. The forest has been broken by the nearby train line. Those left in the community still must take its wood because the winter is harsh enough that a fire burning most of the time is needed to stay warm. It seems that, outside the man she meets and a mysterious image of a young girl in a red cape near the well, the village houses only old women. The decrepit state of winter in a previous hot part of the world and need for wood has the woman in the story shaken. While her landlady warns her that she should not go near the forest, that it can be dangerous, especially at night, the woodcutter she meets laughs and says it’s not a forest, just a copse. I got a sense that timelines in history were intersected and was struck by the proximity of copse with corpse. You have a very old and new story in “Little Red Drops.” The woman wrestles with how to become whole again, and how in this strange winter town, time seems to have stopped.

I asked Marian about Andalusia, where she was born–and how it had changed in her lifetime, particularly in regards to climate change and ecological destruction. Marian told me:

I was born in Andalusia, in Cádiz. This is a place which breathes history: the oldest continuously inhabited city in Europe. Town planning is very complicated, because as soon as you start to dig up the ground to lay foundations for whatever you’re building, you come across Roman or Phoenician remains and have to call in the archaeologists. It is also a city with a very strange geographical situation: it is built on a spit of land sticking out into the sea, and looks a little bit like a dandelion when you see it on satellite images. And the sea changes everything: the seven kilometres of urban beach are regularly washed away (the council brings in sand from Africa to replenish the beach in the tourist season), and the bay has within recorded history been silted up and dredged. So my concept of the environment based on my childhood and upbringing is both synchronic and diachronic: you can drill down into history, but also the world changes around you on a daily basis. And the grotesquerie of shipping in African sand for a European pleasure beach seems like a good metaphor for various types of globalisation and ecological (mis)management and commodification.

I asked about “Little Red Drops” and about how she had imagined the forest, if she had been to one like it:

I went to university in Scotland. The scrubby landscape of Andalusia was a clear contrast to the landscapes that were easily available a short train ride away from Glasgow and so the latter imprinted themselves quite forcibly on my mind. I also have a long association with and interest in Russia, and the north of Russia, near St Petersburg and Finland, is another important space for my imaginary. The forest is in many ways a composite of bits of my memories and my desires and ideas, but it is also a ‘distorted’ version of Andalusia, an Andalusia looked both through these lenses and through a dystopian idea of a snowed-in world.

We also talked about fiction that addresses climate change and extinction, along with eco- and weird fictions. Marian said:

Well, the intersection between ecology and the Weird is one of the things I’m writing my doctorate about, so I could speak about this for hours. But in the interests of concision, let me just say that one of the key tenets of the Weird is the idea of the irruption, the entry into apparently ‘normal’ space of the abnormal invader. This corresponds to the Lacanian idea of the Real: the abnormal invader is actually a glimpse of the unmediated, unvarnished, incomprehensible ‘truth’ that stands outside the symbolic and imaginary interpretations of the world we throw up around ourselves. What eco-fiction is giving us is a world in which the Real (environmental forces that are beyond the control of any single individual) is more absolutely present, and this incomprehensible cosmic truth that previously we only saw in glimpses is now breaking through to display itself to us on a day-to-day basis. Of course, this is not to say that in the world outside of fiction there aren’t people whose devotion to the symbolic or imaginary order of things isn’t strong enough for them to live their lives in a state of denial…

Note: you might also want to read my cursory introduction to “Exploring the Ecological Weird” over at SFFWorld. See parts I, II, and III to find out more about weird fiction and how it intersects with landscape and lost objects.

While the book Lost Objects slinks into the uncanny, offering new perspectives of the world, in reality Andalusia is of course being affected by global warming. Climate Change Post notes several studies which conclude: a widespread rise in annual average temperature since the 1970s, rainfall variability and decreased precipitation across Spain, more winds and storminess, retreat of nine European glaciers–including the Pryenean (the Pyreneeshave have lost 90% of glacier ice in the previous century), sea temperatures rising in the Catalan and Mediterranean seas, air temperatures increasing among persistent extreme summers, and more intense heat waves. The data is sobering, but fiction may also connect us on an emotional level to the realities on the planet. Marian pointed out:

…Any tool for raising consciousness, whether it is emotional or scientific or statistical or whatever, is valid. I realise that saying this runs the risk of continuing to further entrench fixed positions, but I don’t think there’s a divide to speak across in this instance. If the house is on fire, there’s no point arguing with the person who says it isn’t. As far as representing the problems of climate change in an emotional fashion is concerned, I think maybe one way to avoid manipulativeness is to show the continuing validity of Donne’s ‘no man is an island’, to represent the fact that we are all—from the level of the planet down to that of the community, the neighbourhood, the family—connected to one another, and our actions cause joy or pain to those around us.

More about Marian, from her blog: Marian Womack is a bilingual writer. She is the founder of indie press Nevsky Books and worked for nearly a decade in publishing before becoming a postgraduate researcher at the Anglia Ruskin Centre for Science Fiction and Fantasy. Her genre-bending fiction gained her a place in the Clarion Writers Workshop, and in the Creative Writing Master degree at Cambridge University. Marian’s writing is concerned with loss, nostalgia and nature, and her research explores the connections between the weird and ecological fiction. Other research interest are heritage in narrative, storytelling and the Anthropocene, genre publishing and translation. Her fiction in English has appeared in LossLit, Weird Fiction Review, SuperSonic, Apex, or the anthologies The Year’s Best Weird Fiction, vol. 3 and EcoPunk! Speculative Tales of Radical Futures. She has also been translated into Italian and she has written for videogames. Lost Objects, a collection of tales about ghosts, loss and landscape, is now available from Luna Press Publishing.

More about Marian, from her blog: Marian Womack is a bilingual writer. She is the founder of indie press Nevsky Books and worked for nearly a decade in publishing before becoming a postgraduate researcher at the Anglia Ruskin Centre for Science Fiction and Fantasy. Her genre-bending fiction gained her a place in the Clarion Writers Workshop, and in the Creative Writing Master degree at Cambridge University. Marian’s writing is concerned with loss, nostalgia and nature, and her research explores the connections between the weird and ecological fiction. Other research interest are heritage in narrative, storytelling and the Anthropocene, genre publishing and translation. Her fiction in English has appeared in LossLit, Weird Fiction Review, SuperSonic, Apex, or the anthologies The Year’s Best Weird Fiction, vol. 3 and EcoPunk! Speculative Tales of Radical Futures. She has also been translated into Italian and she has written for videogames. Lost Objects, a collection of tales about ghosts, loss and landscape, is now available from Luna Press Publishing.

The featured image of cork oaks in the Parque natural de Los Alcornocales is used in accordance with GPL.