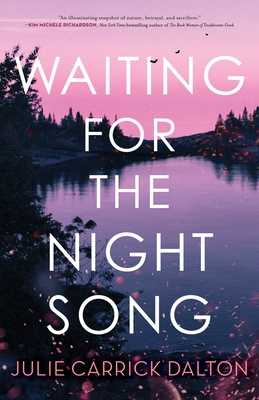

I talked with Julie months ago and am finally happy to be able to share her interesting story! Julie Carrick Dalton is the author of the forthcoming novels Waiting for the Night Song (Forge Books, Jan. 2021) and The Last Beekeper (2022.) She grew up in Maryland and on a military base in Germany. She now lives outside of Boston with her husband, four children, and two dogs. She earned a Master’s in Creative Writing and Literature from Harvard University Extension School and is a proud graduate of GrubStreet’s Novel Incubator. Her news articles, features, essays, and blog posts have appeared in publications including The Boston Globe, BusinessWeek, Inc. Magazine, The Hollywood Reporter, Electric Literature, The Writer Unboxed, and DeadDarlings. Pre-publication, her manuscript for Waiting for the Night Song won the William Faulkner Literary Competition and the Writer’s League of Texas Award for Contemporary and Literary Fiction. Julie also owns and operates a 100-acre farm and enjoys skiing, kayaking, and hiking.

Mary: It’s so great to extend our Women Working in Nature and the Arts series, and I’m glad we’ve met. You’re a writer, mother, speaker, organic farmer, kayaker, and so much more. You’re also writing two novels. Can you explain what’s going on in them?

Mary: It’s so great to extend our Women Working in Nature and the Arts series, and I’m glad we’ve met. You’re a writer, mother, speaker, organic farmer, kayaker, and so much more. You’re also writing two novels. Can you explain what’s going on in them?

Julie: Thanks so much for including me in this series. Both of my forthcoming novels have speculative elements linked to climate change. My debut novel Waiting for the Night Song, hinges on a slow increase in temperature in a fictional New England town. The temperature increase threatens native species, triggers drought, invites a non-native insect in, and leads to crop failures, farm foreclosures, and economic disruption. The changes are all subtle and slow, not the result of a single catastrophic event. In real life, the area where I own a farm has seen the growing season expand by twenty-two days in less than a century because of a slow, steady increase in temperature. It made me wonder what other quiet ways the temperature increase has altered life in the area. In my book, I increased the heat, the pressure, and the stakes, and forced two long-estranged friends to confront the secret that tore them apart years earlier. My second novel, The Last Beekeeper, is about a greenhouse worker who must unravel some unimaginable secrets kept by her ailing beekeeper father after the unexpected collapse of the pollinators sends the world into agricultural chaos. While both books have speculative elements, I hope they feel like they are grounded in our present reality, like the events in my stories could happen at any moment.

Mary: What other novels inspired you throughout your life, and why?

Julie: My first literary BFF was Laura Ingalls. I wanted to live in a little cabin in the big woods, churn butter, grow food, and darn my own socks. As an adult, I gravitated toward novels by Barbara Kingsolver. In particular, Flight Behavior and The Poisonwood Bible had a big impact on me because of the way they engage the natural world. Leni Zumas’ Red Clocks was also a great inspiration to me. I admire the way she presents a world that feels very much like our own, but she alters one significant element: she introduces the Red Laws. I tried to do something similar in my books—create a familiar world, but with a speculative element that changes everything.

Mary: What are the Novel Incubator and the Novel Generator?

Julie: The Novel Incubator and the Novel Generator are programs run by GrubStreet, a writer’s organization in Boston. The Generator is a nine-month class designed to help writers complete a first draft. I wrote the first draft of Waiting for the Night Song in the Generator. The Novel Incubator is a competitive, year-long, MFA-level novel intensive in which ten writers work together with an instructor to revise all ten novels three times each over the course of a year. It is grueling, but it was the best thing I’ve ever done for myself. I not only finished my book, but I found a writing community that I will be part of for life.

Mary: I’m really curious about what happened to 40,000 dead honeybees. Were you a beekeeper and can you explain colony collapse disorder?

Mary: I’m really curious about what happened to 40,000 dead honeybees. Were you a beekeeper and can you explain colony collapse disorder?

Julie: I started keeping bees as a hobby several years ago. I read as much as I could about bee behavior and biology. I’m fascinated with the way a hive works as a single unit for the good of the collective. Their navigation and geometry skills are brilliant. My bees died, but I was never able to confirm why. I assume they were victims of Colony Collapse Disorder, a phenomenon killing off bees all around the world. There are plenty of theories about why the bees are dying: pesticides, rising temperatures, loss of habitat, monoculture farming, or a combination of these influences. It’s pretty clear that we’ve created an environment which is becoming more and more inhospitable to pollinators. In THE LAST BEEKEEPER, I imagine what the world would be like if the bees suddenly disappeared. I plan to restart my beehive soon. I love bees too much to give up on them.

Mary: Interesting. We are finally getting some beehives ourselves this spring!

When you were a kid, you wrote some scripts for Wonder Woman and Mork from Ork. Can you tell us more about that?

Julie: I’m laughing at that question because they weren’t real scripts. They were fan fiction written and illustrated in crayon when I was in elementary school. Although, at the time, I thought they were brilliant. My friends and I used to act them out. I still have some audio recordings of the Mork from Ork scenes. Storytelling is definitely in my blood. My mother ran a puppet theater when I was little. She wrote all her own scripts and did all the voices and puppetry by herself. I worked as her assistant and even wrote and produced my own show when I was ten. I’ve been writing ever since — as a journalist, a short story writer, and a novelist. I recently started performing in story slams too. I won the first slam I entered and was immediately hooked.

Mary: What about your self-description “soil nerd”–you actually love things like worms and fungus. I don’t think you’re alone in that!

Julie: I’ve always loved science. I entered college as a biochemistry major then switched to journalism because I couldn’t stay away from stories. But I never got over my love of science. Eight years ago, when a 100-acre tract of land near our family home went on the market for timber and development, potentially driving out countless moose, bear, and deer, I bought the land to develop a small farm and preserve the forest. I built a barn, fields, and pastures, and preserved about ninety-two acres of woods. Because the land had been a forest floor, there had never been any chemicals in the soil, but it was naturally acidic. It needed work. I read everything I could about ways to amend and build up my soil organically. Soil microbiomes are fascinating. There’s so much more going on under the surface than I realized. Soil complexity will play a starring role in my third novel. The ideas for all of my books grew out of phenomena I’ve observed in nature.

Mary: It sounds like you’ve done some uniquely great things so far in your life, but one of your biggest concerns today is the climate crisis, which you both speak and write on. Where do you speak, and what sort of audiences do you speak to?

Julie: Talking about and writing stories that engage the climate crisis feels like the perfect way to bring my passions for science and storytelling together. I speak at schools, colleges, bookstores, and conferences on the topic of literature that addresses climate change. The first thing I always tell folks is that I’m not a climate scientist. I’m not an agriculture expert. I don’t pretend to be. I have infinite respect for the scientists doing the real work. But as a reader and writer, I believe narrative plays an important part in how we communicate the climate crisis. Sometimes fiction can convey truths that facts alone cannot impart. Sometimes it takes story for a person to imagine themselves in the aftermath of a hurricane like Katrina, in a future US where water scarcity causes war, or in a world without bees. Once a reader connects with characters in these situations, they develop empathy. They see more than just maps of coastlines threatened by rising seas. They see vulnerable humans and fragile ecosystems. They see themselves. Writers have the opportunity to bring more people into the conversation about climate. We can help people imagine What if? Plot, character, and storytelling are always the most important elements of a novel, but within those stories, writers have the opportunity to explore the choices, values, ethics, justice, and politics related to how we talk about and respond to the climate emergency.

Mary: What else are you working on?

Julie: I’m still revising The Last Beekeeper, and I recently outlined what I hope will become my third novel. I’m not ready to discuss the new book yet, but I’m wildly excited about the premise. Like the first two books, this new project has climate-related themes, but this one is more experimental. And a lot darker.

Mary: Wow, looking forward to that! Thanks so much for your time, Julie. I guess it’s an exciting adventure for right now as you publish your debut novel.

For more about Julie, see her website, Goodreads, Facebook, and Twitter.