Click here to return to the world eco-fiction series

About the Book

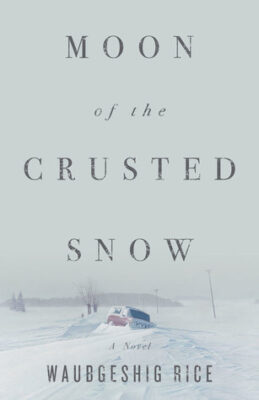

Moon of the Crusted Snow (ECW Press) kept me suspended and occupied over a few nights, and I was very happy to virtually meet up with the author, Waubgeshig Rice, to ask him some questions about his writing, growing up in Anishinaabe culture, and more, including news about his follow-up novel, Moon of the Turning Leaves. Moon of the Crusted Snow is described as a daring post-apocalyptic thriller from a powerful rising literary voice.

Moon of the Crusted Snow (ECW Press) kept me suspended and occupied over a few nights, and I was very happy to virtually meet up with the author, Waubgeshig Rice, to ask him some questions about his writing, growing up in Anishinaabe culture, and more, including news about his follow-up novel, Moon of the Turning Leaves. Moon of the Crusted Snow is described as a daring post-apocalyptic thriller from a powerful rising literary voice.

With winter looming, a small northern Anishinaabe community goes dark. Cut off, people become passive and confused. Panic builds as the food supply dwindles. While the band council and a pocket of community members struggle to maintain order, an unexpected visitor arrives, escaping the crumbling society to the south. Soon after, others follow.

The community leadership loses its grip on power as the visitors manipulate the tired and hungry to take control of the reserve. Tensions rise and, as the months pass, so does the death toll due to sickness and despair. Frustrated by the building chaos, a group of young friends and their families turn to the land and Anishinaabe tradition in hopes of helping their community thrive again. Guided through the chaos by an unlikely leader named Evan Whitesky, they endeavor to restore order while grappling with a grave decision.

Blending action and allegory, Moon of the Crusted Snow upends our expectations. Out of catastrophe comes resilience. And as one society collapses, another is reborn.

Chat with the Author

Mary: You grew up in the Anishinaabe culture. What was that like, and what novels did you like to read when growing up?

Waub: Growing up in my home community of Wasauksing First Nation was the greatest gift. I was surrounded by family, my culture, and the natural beauty of the Georgian Bay region from day one. I was fortunate to grow up in a time in the 1980s and 90s when my community was reconnecting with and revitalizing Anishinaabe culture. I had a front row seat to a renaissance of sorts that involved ceremony, language, storytelling, and more. I learned how to sing and drum, dance at powwows, and partake in sacred ceremonies. I’ll be thankful for that for the rest of my life.

As a kid I had a pretty mainstream exposure to literature. I don’t remember many books from my childhood and adolescence that had a huge impact on me. I gravitated more towards fantasy and science fiction novels, I think, because they really triggered my imagination. In high school I was of course exposed to the so-called classics that were part of the Ontario curriculum. But back then in the 1990s there were virtually no books by Indigenous or Black authors in that curriculum. Thankfully, I had an aunt who knew I was keen on fiction reading and writing, and she gave me books by Indigenous authors like Richard Wagamese, Lee Maracle, Thomas King, Louise Erdrich, and more. Reading those novels as a teenager changed my life.

Mary: In Moon of the Crusted Snow, which is about a community in northern Ontario whose power goes out, along with seemingly the rest of the world around them, we find a dystopian world that seems to be coming to an end. But that’s not all. We also find resilience in the community, and it’s no surprise because the Anishinaabe have seen many ends but keep going. According to the eldest member and spiritual guide in the novel, Aileen, ends and beginnings have always been there. We see it also has to do with continued white-man destruction, over and over. What makes the Anishinaabe so strong and able to survive? What can the rest of the world learn from your experiences?

Waub: That moment between Aileen and Evan was inspired by a conversation I had with my grandmother when I was in my early 20s. She reminded me that it was her grandparents’ generation that was displaced from their original home on the Georgian Bay mainland and forced out onto the island where our community is now. She said they told her stories about how devastating that was, and then everything that followed exacerbated that devastation, like children being kidnapped and forced into residential schools, the ongoing oppression of the Indian Act that forbade culture and ceremony, and so on. That was the end of the Anishinaabe world as her grandparents knew it. And she wanted me to remember I was only a few generations removed from that. So when you’re forced to survive an apocalypse, you have no choice but to try to be strong to survive. Resilience is a crucial human trait for sure, but when it comes to a lot of Indigenous nations, it’s something that’s a direct result of surviving a brutally imposed new world order. That perspective is important for people of all backgrounds to remember, especially here in Canada, which is really only starting to reckon with its own violent and shameful history.

Mary: We don’t really know anything about the novel’s apocalyptic event, which, like Cormac McCarthy’s The Road and Jean Hegland’s Into the Forest, isn’t told about in detail and lends to the mystery about what’s going on. This suspends the reader, who just knows that power is out, presumably everywhere. The reader then focuses on this isolated community and how it survives without outside knowledge, electricity, and so on. This is a strong narrative. What kind of things inspired you to tell the story this way?

Waub: The Road was definitely a significant source of inspiration when dreaming up this story. When I first read it, I really appreciated how the cause of the apocalypse is unknown, which kind of ups the creepiness of the overall story. It’s somehow scarier when you don’t know what ended the world, because it’s harder to come to an emotional resolution. I made the community in Moon of the Crusted Snow remote for that reason: during a mysterious crisis like this, it’d be nearly impossible to understand the entire scope of the cause because of the distance, both geographically and socially. I originally thought about placing the community on Georgian Bay, where I’m from, but when I mulled it over, the tension I wanted to create didn’t seem to fall into place, I think because of the proximity to the big cities of Southern Ontario. It’d still be dramatic, but in a much different way, which got away from the spirit of the story I wanted to create. Also, it was always meant to be a shorter novel, so there purposefully wasn’t the room to explain or try to understand what happened to trigger the blackout. Pacing was really important, and I didn’t want to get too bogged down in exposition.

Mary: I caught a reference to a story keeper in the novel, which is something I first heard at a speaker presentation in Vancouver, when Cherie Dimaline talked about her novel The Marrow Thieves. What is a story keeper? I’m so curious and in love with this idea. We recently had a weekly question on a Discord I’m in about our favorite local odd or cool museum, and I thought of the cultural and artistic preservation of stories and what would happen to them after climate events and other ecological catastrophes happen. Obviously, the first thing people would worry about would be the essentials like food, shelter, clothing, and energy sources. Then, though, our second thoughts might be how to preserve our stories and other cultural and more artistic events.

Waub: I honestly haven’t thought about that term beyond the basic definition that you’ve sort of outlined. Everyone, regardless of culture or background, is a story keeper and has the capacity to share stories and speak their truth. I don’t really see it as any deeper or more profound than that. But it is important to acknowledge the survivors of colonialism who have held on to the stories and cultural knowledge that were long forbidden and shamed by the Canadian state. These people risked their lives—many of them while children—to hang on to their stories and ceremonies, in hopes of one day being able to share them again. And now thankfully many of them are, as revered elders. So getting back to what we went over earlier, keeping stories is essential to survival. After the end of the world, Indigenous people have been able to piece their cultures back together, despite the brutality of what they and their ancestors endured.

Mary: Environmental preservation is also key, and for Anishinaabe, and most Indigenous peoples around the world, living within one’s means, respecting what nature gives us, and building community around that seems important. How do you, as a storyteller, consider more ends coming our way, such as climate and ecological changes, and how do you write that into stories?

Waub: I think the COVID-19 pandemic was a good reminder for the whole world just how fragile all of our systems are. In the early days of the pandemic, I was really encouraged by how people were reconsidering their roles in food security and climate change, and other major issues. When everything shut down and store shelves were being depleted, some people started thinking more about small-scale agriculture, community gardens, and other food initiatives to support themselves and their communities. It was a direct response to what seemed like a world-ending event. And when there were images being shared of clear skies and reduced air pollution because of less commuter traffic, people noticed, and that was really encouraging to see. That remarkable shift is something Indigenous people everywhere are familiar with. Unfortunately, those attitudes and ideas didn’t persist through to this point of the pandemic, but at least the shock was a good reminder for people. And that falls in line with one of the major themes of Moon of the Crusted Snow. When all our modern luxuries and infrastructures collapse, it’s the land that will sustain us, so it’s important to maintain a good relationship with it. That’s what I learned growing up in my home community, and it’s fairly natural for me to adapt those worldviews into my fiction writing.

Mary: I read that you have finished the draft of your sequel, Moon of the Turning Leaves, coming out in 2023. What will be happening in that novel?

Waub: It takes place ten years after the end of Moon of the Crusted Snow. After spending so long in their new settlement in the bush, the community realizes many of the natural resources around them—mainly the food sources—are depleting. They acknowledge they’ve been stationary for too long and need to move, as their ancestors regularly did. So the community leadership decides to send a group south to explore what’s left of the world—if in fact it has ended—and to see if it’s feasible to return to their original homeland on Georgian Bay. A team of six is formed, included Evan and his daughter Nangohns, who’s now 15 and an expert hunter. It’s a quest story that reveals their new future, and further rekindles their relationship with the vast, rich land of their home territory. It’ll be published on October 10.

Mary: I’m looking forward to the next book. Thanks so much for your time! I really appreciate learning about your inspirations, cultural upbringing, and thoughts about storytelling.

Author Bio

Waubgeshig Rice is an author and journalist from Wasauksing First Nation. He has written three fiction titles, and his short stories and essays have been published in numerous anthologies. His most recent novel, Moon of the Crusted Snow, was published in 2018 and became a national bestseller. He graduated from the journalism program at Toronto Metropolitan University in 2002, and spent most of his journalism career with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation as a video journalist and radio host. He left CBC in 2020 to focus on his literary career. He lives in Sudbury, Ontario with his wife and three sons. His forthcoming novel, Moon of the Turning Leaves, will be published in October 2023.