Click here to return to the series

Intro

This month we travel to the world of Motswana author Tlotlo Tsamaase, whose short story “Eclipse Our Sins” rocked me in a good way. You can read the story at Clarkesworld. I featured this story in my last article at Medium, Part II of my Around the World in 80 Books series, which examines climate- and ecological-themed fiction from everywhere. I was so happy to finally touch base with Tlotlo and talk with her about Eclipse as well as her other writing and work. “Eclipse Our Sins” is a fascinating short story, which cries out against the grotesque evolution of our world and how nature has been suffocated in the hands of takers and users. It’s a brilliant, riveting prose-like story in which stark imagery comes alive, painting a crime-ridden place where evil-doings against natural landscape and culture go hand in hand.

Chat with the Author

Mary: Your writing includes fiction (mostly speculative or horror), poetry, and architectural articles. I attended an Ecocity summit in Vancouver, BC, so I was drawn to that architectural aspect of your work and would love it if you could talk some about Ecocities.

Tlotlo: I’m going to outright quote an article I wrote some years back for Boidus Focus, a local built environment newspaper, which is a bit relevant to this question: “Eco-cities illustrate the scramble to reinvent cities in juxtaposition to their sibling-cities with a core focus on sustainability. Eco-cities are synonymous to built from scratch self-reliant satellite cities that maintain an eco-friendly environment from which everyone can lead healthy and economic lifestyles. Ultimately, this would mitigate the congestion in urban areas. As such, there is the escalating environmental concern regarding global population, which is estimated to reach around 10 billion in 2050 from its current 7-billion state. On a larger scale, eco-cities have been experimented with, like Masdar City in Abu Dhabi, PlanIT Valley in Portugal, Tianjin Eco-city in China, Amanora Hills in India etc. Other African eco-cities are Konza Techno City in Nairobi (claimed as Africa’s Silicon Valley), Appolonia in Ghana, Roma Park in Zambia and Angola’s ghost town Luanda is Nova Cidade de Kilamba, amongst a few.”

Although, the unfortunate thing is sometimes realizing these big ideas is hemmed in by corruption and an abandonment of the very sustainable ideas a country is trying to uphold, which keeps out the necessary professionals or even the issues on ground, like poverty, and ultimately the eco-city either becomes a ghost town or less sustainable than it set out to be.

Mary: Can you describe what gives impulse to your fiction and poetry?

Tlotlo: Firstly, writing comes from a place of passion. And most often it’s a need to process issues in our world—racism, climate change, gender-based violence (GBV), culture, technology etc.—in a way that is consumable to a reader through plot and characterization. But the interesting thing is manipulating our reality by exploring an alternative world and its ideas. Writing is also blank page to paint your pain across, a very cathartic experience depending on the writing’s topic and themes, and some people relate to that. The beauty of writing also allows one to read from different perspectives and see how the other side of the world lives or dreams. These, I believe, give me ideas that trigger me to start writing.

Mary: When I researched for a recent article at Medium, which goes around the world exploring eco-fiction, I always walk away later with great discoveries, which is how I found your story “Eclipse Our Sins,” which I included in the article. The article spotlights 10-12 pieces of fiction from every continent. Trying to sample the continent of Africa is interesting, as works are so diverse. Some of the common themes I’ve seen deal with colonialism, the spiritual world, and speculative fiction, such as in Africanfuturism. Where do you write from, and how do place and environment inform your writing?

Tlotlo: I write from many places. The thing about speculative fiction is you can bend reality and create an entirely different universe from ours, by either extrapolating our current day issues or turning them on their head and seeing how that affects the family, a character or even a village. So basically, I try to analyze the micro and macro parts of our world, whilst dissecting the emotions through the lens of climate change. In one way, a writer can create a utopian universe, freeing its characters from the oppressive conflicts of our current reality, although conflict always rises. In another way, writers can process the dark side of our world. “Murders Fell From Our Wombs” comes to mind, a horror that explores GBV in a murderous village. One tries to analyze the psychology of abuse, racism, and its effect on the person, the community.

When I was studying architecture, my first year was such a culture shock; we didn’t know what it took to realize buildings into reality. What it takes to root architecture to a place is the environment, the land, the people, the culture. One way or another a building is either ignoring all these elements or embracing them. We’d go out to site to heavily analyze and document the culture of the area as well as the natural environment, such as topography, wind and rain elements, soil details, the patterns of people’s movements, their daily activities, the local material, culture which dictated rituals. If we didn’t respond in any way to this analysis, our lecturers called our designs “floating designs,” that they could literally be put anywhere in the world and you wouldn’t be able to tell where they came from or who they are. So our designs—and as I try with my writing—has to be rooted to place, one way or another and if you’re ignoring it, it should be for a good reason.

So I try to explore that in some of my writing because that is how I was taught to process ideas and develop them. You have to ask yourself, what is this place that this character lives in? What is their background, their motive, and their conflict? What issues exist that prevail them from reaching their goal. How did they grow up, how is their culture and rituals like? What would happen if you fused this traditional element of this place with technology? What would become of it and the people and would it change them for the better or worse? A person’s belief system also influences how they behave. So you have to understand what is the character’s belief system, and most often it can be tied to the land, the plants, the trees, etc. Also nature is free all around us. For example, a passive-designed building, depending on its material use, can use its environment for cooling (reducing heating and cooling costs), can use deciduous trees to block the summer sun and let in the winter sun, to redirect winds, etc. We either use them or ignore them. And so I could see nature as either a passive or active character in a story. Earth as a character that we abuse or loved, which also inspired the story “Eclipse Our Sins.”

Mary: Can you explain more for our readers what “Eclipse Our Sins” is doing and what motivated you to write it?

Tlotlo: It was an amalgamation of many things: climate change, crimes, fear, pain. It came from a suffocating cooker-pressure moment of being inundated with scorching news reports of police shootings of black men, of gender-based violence, of black women being murdered horrendously, the pollution, the deforestation, the toxic buildings we throw people in just for budget cuts, corruption for wealth, the raping of the environment for wealth, the oil spills, the racism, the killings, the xenophobia, the poor animals—it’s too much. I saw Mother Earth as a very wounded but angry soul, finally empowered to avenge her pain, which the future younger generations unfortunately have to bear. So it was a deconstruction of how our current pleasures (peoples’ greed for wealth and power and materialism) sacrifices the future generation; the main character laments in one scene: “Mmê Earth, You used to be so healthy for us . . . until we destroyed You. I understand now why You want to purge us from Your womb. But it is unfair. How come we are the ones to suffer for the before-generation’s desires that smoked our future? I hate them. I hate them all.”

Much like my short story, “Murders Fell From Our Wombs”—which explored curses in a village setting as well as the stereotypical representation of women—the environment is an antagonist. In “Eclipse Our Sins”, the environment is also an antagonist and a somewhat savior as it’s retaliating for the abuse it underwent. I wrote “Eclipse Our Sins” out of sheer experimentation for how we abuse the Earth and people similarly. I’m quite a fan of true crime, and it’s devastating to hear how people go missing or are murdered and found in horrid, random places; in addition, I am a Black woman—you can imagine the layering of abuse black women go through, so I was fed up and this was my catharsis. In “Eclipse Our Sins,” at least you are safe from the evil acts of people because Mother Earth enacts punishment instantly and the question becomes: is that to create a utopian world? But everyone’s definition of utopia varies. I also meditated on the fact the that the ground, the trees, the air, the natural environment see everything of say a horrid crime, so I wondered what would happen if the elements had the voice and power to stop something like that from horribly happening. And if these elements have power, then there is power in an illness. Depending on what you believe in, you’ll have a group of people who believe that the root cause of a disease or illness goes further than the physical symptom, and that the mind is a very powerful organ. So in this story, characters’ sins manifest as illnesses in their bodies; what you do can destroy you.

Mary: I love how the story delves into climate change along with other pollutions. I love this line:

“Warning! Pollutants rife in the air, in the city: carbon emission, racism, oil spills, sexism, deforestation, misogynism, xenophobia, murder…” How important do you think it is for writers to recognize our natural world in terms of human experience, and how have you done this in other writing, such as “Eco-Humans”?

Tlotlo: Eco-Humans was actually the point in time I learned that you can design every detail of a building to respond to sustainability, weather, or the sun, whilst managing the costs to build and run it. So I wondered what if humans were just like buildings. What if the environment became so toxic, that every part of them had to be tempered in order for them to survive? What if all the elements that used to be free—air, sunlight—could no longer be easily absorbed into their bodies? Of course, you’d have companies trying to profit from this, and the poor communities, how would they even survive? What if you could control how much air they could breathe, and what if it became too expensive to do that? If you manipulated them biologically as you did buildings to be eco-friendly, what would that world be like?

I believe studying architecture has forced me to consider the natural environment, because it influences our lives. It becomes saturated with everything around it, culture, our actions, etc. Without it we are quite nothing. The actions we impose on it are as similar as actions we impose on other people, hence why the line above carries parallelisms between pollution and say for example racism; we abuse earth and now it’s retaliating as I suppose some people would. I believe writers are just like architects, designing and creating worlds. In class, we were taught to design our buildings that respond to its situated environment and climate—that response could either be conforming or opposing–but one should have a valid reason for their design’s response. So writers, I see them the same way, creating and designing written works, situated in different parts of the world, perhaps always responding to something.

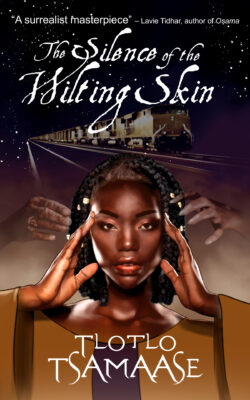

Mary: You have a new novel out, The Silence of the Wilting Skin (Pink Narcissus Press, May 2020). The cover and title alone are intriguing. Can you describe this novel as well? I imagine that Covid-19 changed the way you were able to participate in readings and signings?

Mary: You have a new novel out, The Silence of the Wilting Skin (Pink Narcissus Press, May 2020). The cover and title alone are intriguing. Can you describe this novel as well? I imagine that Covid-19 changed the way you were able to participate in readings and signings?

Tlotlo: The Silence of the Wilting Skin is about a young woman trapped in an oppressive city that’s erasing every part of their identity. In the African city, the nameless young woman living in the wards slowly begins to lose her identity: her skin color is peeling off, people are becoming invisible, and the city plans to destroy the train where they bury their dead. After the narrator is given a warning by her grandmother’s dreamskin, things begin to fall apart. Struggling to hold onto a fluctuating reality, she prescribes herself insomnia in a desperate attempt to save her family. It explores personal identity and the various ways we experience loss.

Here’s a beautiful summary from Publishers Weekly: “Through magnetic prose, dream logic, and lush imagery, Tsamaase delivers a fierce political message. Suffused with both love and righteous anger, this atmospheric anticolonialist battle cry is a tour de force.”

Yes, Covid-19 definitely changed things. Everything honestly was done virtually and is still being done virtually so, really, bless the internet!

Mary: Does this story happen in a specific place?

Tlotlo: The story doesn’t take place in a specific place, but it does take place in Africa on a fusion of ideas and inspirations; although, parts of the setting were based on our city’s urban planning issue. For example, the train tracks that divide the two cities in the novella were based on the train tracks that in a way divide our city, which has led to traffic congestion and lack of ease of movement between both sides for pedestrians and vehicles, especially the CBD where they pass. Of course people can move in and out of these sites; it’s just that certain things could be accommodated to make it easier for both parties. So that’s the train you see on the cover. Secondly, some beliefs in the story are based on myths we heard as kids. For instance, we were told that when dreaming and we see someone dead in a train calling us, don’t get on; otherwise, you will never wake up. Hence the dreamskin people and the dead people on the train and the ancestral realm that speaks to the spirituality and beliefs of some African cultures. Thirdly, some of the structures that were described relied on either traditional architecture in Africa or western architecture; hence why you see two cities on either side of the train.

Mary: Anything else you would like to add?

Tlotlo: Well thank you for this lovely interview!

I have a couple of forthcoming projects, so the only way to find out is to head over to my website and subscribe to my newsletter or join my Patreon, which is where I provide sneak peaks of upcoming works, releases and post details of my work and process. Either way, you can contact me to say hello, tell me how your day has been, or send in questions.

Mary: Thanks to you too! I enjoyed getting to know your writing and you a little better.

About the Author

Tlotlo Tsamaase is a Motswana writer of fiction, poetry, and architectural articles. Her work has appeared in Terraform, Apex Magazine, Strange Horizons, Wasafiri, The Fog Horn magazine, and other publications. Her poem “I Will Be Your Grave” was a 2017 Rhysling Award nominee. Her short story, “Virtual Snapshots” was longlisted for the 2017 Nommo Awards. Her novella The Silence of the Wilting Skin was published in May 2020 from Pink Narcisuss Press.

You can find her on twitter at @tlotlotsamaase, on Patreon, and at tlotlotsamaase.com.