Click here to return to the world eco-fiction series

About the Book

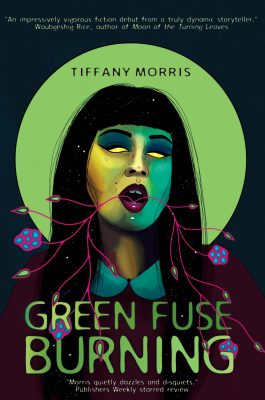

Green Fuse Burning (Stelliform Press, 2023) is “a transformative Indigenous eco-horror novella from Mi’kmaw writer Tiffany Morris.”

- “Green Fuse Burning is an impressively vigorous fiction debut from a truly dynamic storyteller. Tiffany Morris has laid out a concise and creepy tale that mesmerizes as it weaves through several realms, from the tangible to the spiritual. I was captivated by the looming mystery and the striking imagery that carried me like a current to the story’s monumental resolution. This book is a must-read in new speculative fiction!” -Waubgeshig Rice, author of Moon of the Turning Leaves

- “Morris quietly dazzles and disquiets in this weird horror novella … Poetic and grotesque imagery drives the novella’s horror, with fluid narration fostering a sense of disconnect and dread … This is a subtle and refreshing twist on the cabin in the woods trope.” –Publishers Weekly starred review

- “A verdant alienation seeps through every page as Morris reimagines the possibilities of decay, a desperate isolation scouring the mind to reveal a torrid, seething strangeness beneath, the inevitable reckoning gathering its strength below the calm surface of the pond.” -Andrew F. Sullivan, author of The Marigold and The Handyman Method

- “In this Indigenous swampcore novella, Tiffany Morris … masterfully reclaims cosmic horror from its white tradition, and that’s so important because the genre has big problems™ with its philosophy, not just its heritage. I’m in such awe of her execution and the quietness and humbleness of the story, how she spins it all into something meaningful and new. Green Fuse Burning is an astonishing work that processes personal and planetary grief, and leads the reader through a viscerally healing experience.” -Joe Koch, author of The Wingspan of Severed Hands

- “Lush and innovative. You can tell from the start that you’re in for something different. Green Fuse Burning digs its fingers through fertile layers of ecology, grief, and twin apocalypses to explore transformative death with a beauty both isolating and unsettling.” -Hailey Piper, Bram Stoker Award-winning author of Queen of Teeth

- “This book is strongly recommended for anyone looking for a layered narrative of dark fantasy, ecological awareness, queer and indigenous politics, in an inventive hybrid form.” -Joshua Gage, for Cemetery Dance Magazine

Chat with the Author

Mary: Your poetry and fiction often fall into the category of ecological horror, which is fascinating. What got you started down that path?

Tiffany: Thank you so much! I never really intended to write ecological horror, but I think that this moment we’re living in demanded it of me. My poetry and fiction are always a function of me working through things that are on my mind, and as the reality of climate change becomes manifest in increasingly undeniable ways, there must be an outlet and an alarm—a processing of the grief and horror that corresponds with a global sense of doomed uncertainty.

Mary: We’ll primarily talk about your latest fiction, Green Fuse Burning, but another novel from 2022, Elegies of Rotting Stars, also seems to mix ecology with horror. And you have plenty of short stories, some free to read online, including “Night in the Chrysalis”, which was recently published in the Indigenous dark fiction anthology Never Whistle at Night. I’ve read the book, and the stories seem to be, in part, transformation stories that bring in the natural world as well as the horror of the human world. What are your thoughts on that, and how does horror fit in?

Tiffany: I think that Indigenous cultures have long memories, and with those long memories comes an understanding of the transformations present in everything—good, bad, and indifferent. The Mi’kmaw language is verb-based, and our word for Creator describes the act of creating; the world is always in a state of flux. There is a continuity and cyclicality to time that accounts for change that the terminal and linear thinking of settler-colonial and capitalist temporality does not—and that’s where horror so often emerges.

Mary: Never Whistle at Night, edited by Shane Hawk and Theodore C. Van Alst Jr., follows the premise of many Indigenous peoples’ beliefs that one should never whistle at night: “it can cause evil spirits to appear—and even follow you home”. What was that experience like, working on such an anthology with several other authors?

Tiffany: It’s been wonderful! I loved every story in Never Whistle at Night and feel so honoured to share space with these writers. Shane and Theodore are very thoughtful editors, and they did a lot of great work pulling together diverse writing styles, themes, and Nations in forming the anthology. I discovered writers whose work I hadn’t been familiar with, and now have a very long reading list for the foreseeable future.

Mary: Green Fuse Burning is about a Mi’kmaw artist, Rita, whose girlfriend—without Rita’s knowledge—wins her a residency at a cabin for a week. Because Rita’s father died and she regrets not learning more from him about the Mi’kmaq language and culture, she is struggling with feelings of grief and decides to go ahead and spend the week at the cabin. The cabin is a spooky place with strange noises and dark visions emanating from nature around her, which propel her creativity. What do you want readers to get from this story?

Tiffany: I want readers to see how interconnected grief, trauma, and alienation can be—especially the different forms that branch out from the deep subjectivity of the personal into the world around us. When I’m in the wetlands, the interconnectiveness—a world used by Mi’kmaw Elder Murdena Marshall to bring that sense of inherent interconnectivity into an active space—becomes undeniable. Rita had to be there to come face to face with herself and her grief. It can be hard to meet ourselves deeply, to meet the world deeply, when we’re reeling from major shifts and losses. This challenge also extends to climate change and the accelerating collapse of late-stage capitalism: we’re being encouraged to numb ourselves rather than confront the situation even as it worsens. If we orient ourselves to the darkness we can see more of reality. Darkness can also be the embrace of the swamp—the chirping night where frogs sing, where things can be alive around us.

Mary: I love the idea of interconnectiveness. What kept jumping out at me throughout the novella was transformation and the idea that the horror of death is just the beginning of a new life. It reminded me of some eco-weird fiction I’ve read where charnel grounds, or even like the rot in Andrew F. Sullivan’s The Marigold, where rot and decay abounded, seeping into everything. When I interviewed him, he said, “But I think there is room in the ruins for life. Rot is not pure entropy, it’s a repurposing and a rebuilding, in newer shapes we may not recognize beyond a foul smell.” This trope is often evident in weird and horror stories where the ecology takes part in the transformation. Yours brings Indigenous backgrounds to yours and my landscape (Nova Scotia), the grief of colonization, and the generational trauma that caused. Can you shed light on this?

Tiffany: I loved The Marigold; it was such an interesting exploration of those themes in an urban space. My own L’nu perspective is that our land knowledge needs to be kept continuous—that ability to change alongside it that is part of that greater embrace of change I mentioned earlier. When I’m connecting to land, it can be a grief experience, knowing that intrusions on it made by exploitative and extractive industries have changed how the land looks and operates. But I have great faith in nature’s healing abilities, and the resilience of the Earth and in the enduring survival of Indigenous epistemologies, even when I am grieving.

Mary: Names and descriptions of Rita’s six pieces of art created at the cabin begin some chapters. Rita’s own changes are reflected in her artwork, which is less muted than previously and more experimental and inclusive of the forest, pond, and swamp around the cabin. Have you created art like this? How did you get some of these ideas?

Tiffany: I have not! I wish I was as talented an artist as Rita, but my work tends to just be for fun or as an outlet for the same themes that haunt me when I need a break from writing. I wanted Rita’s creative journey to reflect her increasing understanding of the alliance we make with nature and death in exchange for our limited and sacred time on this planet. Plus I thought they were art pieces I would want to see; some of my favorite artists that Rita draws inspiration from are Rita Letendre, Isaac Levitan, and Kim Dorland.

Mary: Is there anything you would like to add about this book that you want readers to know?

Tiffany: Please read the content warnings and take your time with it if need be! I deeply appreciate people taking a chance on my weird little book.

Mary: I’m dying to know what’s next!

Tiffany: I have a few secret projects on the go—one from Nictitating Books, that will drop later this year! In the meantime, I have a coastal horror, climate collapse story in The Off-Season: An Anthology of Coastal New Weird coming out this fall.

Mary: Wow, okay, I’m going to look for that. Sounds amazing. Thanks so much, Tiff! I really appreciate your time.

About the Author

Tiffany Morris is an L’nu’skw (Mi’kmaw) writer from Nova Scotia. She is the author of the swampcore horror novella Green Fuse Burning (Stelliform Press, 2023) and the Elgin Award-winning horror poetry collection Elegies of Rotting Stars (Nictitating Books, 2022). Her work has appeared in the Indigenous horror anthology Never Whistle At Night, as well as in Nightmare Magazine, Uncanny Magazine, and Apex Magazine, among others.