This review may contain spoilers.

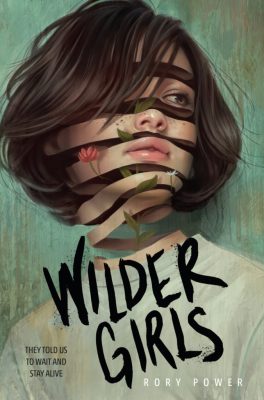

Wilder Girls (Penguin Random House, July 9, 2019) helps to usher in a type of wild fiction that deals with ecological collapse. In the story, teenagers at the Raxter School for Girls are quarantined on an island off the coast of Maine. They’ve been sequestered for a year and a half as a disease called the Tox has spread rampantly throughout the island, manifesting differently in women, men, animals, and plants. The crumbling school on the island is fenced off beyond a strange and frightening forest. The girls have permission to access only the house, a nearby barn, and a portion of the beach, so the story also represents a psychological haunting due to the small living space–a habitat that is being broken down day by day. Finite resources mean that the occupants have to use furniture and other building parts for making fires to stay warm. Other supplies, such as medicine, blankets, and food, are flown in monthly. Resources are sparse and in severe competition.

The main characters take shape early on, particularly the three friends Byatt, Hetty, and Reese. Others, such as Headmistress and a young teacher named Ms. Welch, imitate a sense of authority, though their control becomes questionable and corrupt as the Tox takes hold, kills many, weakens others, and creates a mystery that is suspended at a finger-snap pace throughout the story.

Byatt, Hetty, and Reese seem ordinary at first: vulnerable, curious, competitive, emotionally charged. As the story evolves, they develop an uncanny strength and determination in order to survive, and more importantly, take care of each other. The love here is real; Hetty and Byatt are best friends, like sisters, and Hetty and Reese find passion and become closer friends than previously. But love has a deeper sort of meaning in the story too: doing whatever it takes, when feeling like utter shit, to survive together during ecological and societal collapse. These resilient characters offer a sort of hope I don’t find often when reading fiction, especially horror fiction.

When the girls get the Tox, it manifests differently among them but can include extra spines, bruises, bleeding, vomiting, and a number of physical deformities, like an eyelid that fuses together. Animals and men experience different symptoms. The island has beautifully colored mutated crabs and irises, along with the forest beyond the fence where bears, deer, and other animals prowl and have grown strangely large and weird. Trees in the dark forest seem preternatural. There’s a small scene that reminded me of the genuflecting plants in Michael Berananos’s “The Other Side of the Mountain”. Trees have become taller and thicker and have taken on eerie forms, similar to those in Algernon Blackwood’s “The Willows”. And in the forest are strange metamorphoses, where life and death forms exhibit traits of both animals and plants, similar to those in Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation. These (perhaps non-intentional) allusions to the weird injected an amazing jolt to the story, as literary studies have shown that when bringing the biological/ecological to life in fiction, it often lifts nature up as other or alien to provide the tension that makes a story brilliant and its exploration of the wild profound.

Though elements of the story appear preternatural, there’s still an explanation for it all. So the story kind of hangs you upside-down before entertaining the idea that this might be what we’re in for in our climate-changing world. Prescient clues to climate change exist in the novel all along, too, though, like with many great climate-themed stories, it’s rarely mentioned head-on, rather is hinted at here and there, like with the weirder weather, rising waters, warming temperatures, and species that cannot adapt well in a period of fast ecological change. There’s also one scene that reminisces about how the older generation leaves behind a mess for others to inherit and be responsible for, just like how the teenagers in the story have to figure out what to do next.

Wilder Girls shows what happens when we forget the wild in us, turn a blind eye to our ecologically changing world, and leave our destruction to the next generations. Of course, on the surface it’s a well-paced YA horror queer novel. It rises above though; it’ll open your eyes, folks. Highly recommended!

About the Author

Rory Power grew up in New England, where she lives and works as a crime fiction editor and story consultant for TV adaptation. She received a Masters in Prose Fiction from the University of East Anglia, and thinks fondly of her time there, partially because she learned a lot but mostly because there were a ton of bunnies on campus.

Wilder Girls is her first novel, published with Delacorte Press on July 9, 2019. She is represented by Daisy Parente at Lutyens & Rubinstein, and Kim Witherspoon at InkWell Management.