Click here to return to the series

The global novel exists, not as a genre separated from and opposed to other kinds of fiction, but as a perspective that governs the interpretation of experience. In this way, it is faithful to the way the global is actually lived–not through the abolition of place, but as a theme by which place is mediated. Life lived here is experienced in its profound and often unsettling connections with life lived elsewhere, and everywhere. The local gains dignity, and significance, insofar as it can be seen as a part of a worldwide phenomenon.

-Adam Kirsch, The Global Novel: Writing the World in the 21st Century

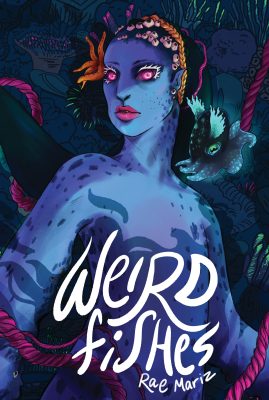

About the Book

Weird Fishes (Stelliform Press, 2022) takes place in various areas in the North and West Pacific Ocean, most particularly in “The Center of the Sea” near the Mariana Trench around Guam and the Mariana Islands as well as the Pacific gyre between Hawaii and California and various marine migration routes. Another inspiration is drawn from the coral off the eastern coast of Moloka’i. The story has two sea creatures navigating a complex relationship and heartbreak in a beautiful, weird, and sometimes brutal adventure. Weird Fishes explores depths unknown and imaginary waves of life lived in an ever-changing sea due to climate change.

Chat with the Author

Mary: Thanks for this beautiful story about seafolk and their fight for survival as well as magical beauty and song. It seems that you have an incredible knowledge of marine biology as well as a storyteller’s imagination to bring it to a story. I love to ask writers about what informed their stories and about what stories they loved when growing up. What are yours?

Rae: Thank you! My stories usually find their sources in real-world inspirations, or I have an easier time pointing to those influences. A lot of the world-building in Weird Fishes—and the unique biology of its characters—was inspired by imperfectly remembered science facts from documentaries, podcasts, and research articles I happened to click on. I don’t have a background in science, so I do rely heavily on storyteller’s imagination to make connections and fill in the gaps, but I’m fascinated by ecosystems and relationships in the natural world and am kind of obsessed with trying to develop a narrative structure to tell this tangled story of a living world in a way our human brains can appreciate. I seem to keep trying to investigate the nature of stories, even in my stories, so it all gets inadvertently meta sometimes.

In Weird Fishes, I described Iliokai’s creative process as transcribing all the sensations she experiences—the refraction of light, chemicals in the water—into sound and song. I liked this idea of an artist or storyteller being a giant whale mouth just gulping down everything and filtering it through some kind of creative baleen, just letting all those influences combine in a mysterious process inside a body and see what comes pouring out.

So it’s weird that I haven’t really thought back on my own early story influences…almost afraid to do a deep dive and explore the junk and wreckage of what my unhinged whale-jaw swallowed as a kid. I thought it’d be a bunch of plastics and crap—but the truth is so much worse! Young Rae had terrifyingly precocious reading tastes. I read everything by Jeanette Winterson, Lorrie Moore, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Milan Kundera…who else? I went through a Will Self phase. I’m not really sure what a sixteen/seventeen-year-old got out of all that. But looking at the list now, I’m like, “Ohhh… It all makes sense.” They’re not really speculative fiction writers—who I enjoy reading and am inspired by now—but I guess there is something weird and fabulist and allegorical about some of their works. And I can see how my irreverence to genre conventions probably has some tangled roots feeding off of those early interests.

Oh, I read Daniel Quinn’s Ishmael when I was like sixteen—because of course I did—and I’m not sure what I’d think about the story now in my big age, but at the time, hearing the history of humanity told through the eyes of a non-human apparently had a huge effect on how I perceive the world. I often imagine what things might look like from the perspective of a parasite, or a tree. And that particular book exposed me to the idea that Western culture is made up of a series of stories it tells about itself—the myths about human nature and how we assume the cobbled together contraption that we call civilization is working because, look, we haven’t crashed yet! Yep, I can see how that might’ve been a formative work of fiction for me.

Mary: Oh, I love creative baleen, and your reading background is so similar to mine! Can you explain this novel in a nutshell, without spoiling it?

Rae: I’m terrible at explaining what this thing is. I usually mumble something about it being a story that “plays with perspectives” and then sort of trail off. However, my publisher introduced Weird Fishes at the book launch in a way where I felt for the first time, that’s it! That’s my book! and I’m so grateful and still a little in awe that she was able to sum it all up so generously.

“On the surface this is an undersea adventure, but it’s also cheeky, it’s bewildering… sharp as glass in its critique of past and ongoing colonial aggression and its effects on the ocean and its creatures.”

Thank you, Selena Middleton, for the nutshell.

Mary: What genres do you explore in Weird Fishes?

Rae: I started out thinking of Weird Fishes as a “first contact” science fiction story: Deep-sea citizens isolated on the ocean floor become aware of an “alien threat” from above. And something I love most about that genre is the theory that contact with alien intelligence assumes there will a dramatic shift in how humanity conceives of itself—when we finally realize we’re not alone in the universe, etc.

There are usually a bunch of colonialist assumptions inherent in that “first contact” narrative that I wasn’t interested in repeating, so I had a fun time flipping and twisting and looking at things from an unexpected angle—and in that dismantling process, I guess it gets difficult to notice its “first contact” sci-fi genre beginnings? It got weird. But I still wanted to get at that people-banding-together-in-the-face-of-global-threat feeling without relying on us-vs-them alien invasion framing—to tell a story that inspires a change in our conception of “what it means to be human” once we realize we’re not alone in the universe, but get there from a different route than colonizing-other-worlds metaphors.

So Weird Fishes is all about those existential tickles of discovering sentient intelligent life, but finding it already exists on this planet—and humans aren’t the ones making that discovery, an ancient deep-sea squid civilization has to wrestle with “what it all means” to find out they’re not the supreme intelligent beings in their world. It’s a little eco-fable about how that perception shift could open up new ways of addressing the climate crisis and ecological collapse. The end.

Mary: Ceph and Illiokai are the main characters, one from the deep sea and the other a closer to surface whale rider. Each is fascinating and well-written. How did you come up with them?

Rae: Ceph is a scientist from that aforementioned deep-sea squid civilization. I think of her as Ellie Arroway from Carl Sagan’s Contact. A character we’re primed to root for with her relatable struggles and a perspective most readers have learned to easily inhabit—cares and concerns focused primarily on her career and well-being of herself and immediate family. Prime protagonist material. Super-smart but oddly clueless about the world outside her sphere. Familiar, despite having eight arms, nine minds, and ability to communicate with colorful skin patterns and chemical secretions. Her kind enjoys a privileged position on the seafloor, no other creature threatens them, which makes them oddly vulnerable when they’re later faced with an existential climate threat. They’ve never had direct contact with humans from above—her culture’s common sense science barely allows for the possibility of life existing where they can’t flourish—but any human encountering her species would just assume she’s a cute octopus with no inner life.

Iliokai looks like a seal, but has features that are distinctly not-seal—a blowhole, disproportionately longer pawfins and a jaw that unhinges wide like a whale’s. She’s a marine mammal who’s had maybe too much contact with humans, and a lot of her characteristics are twists on mermaid traits common in folklore across various sea-faring cultures— ethereal voice, shape-shifting ability, dangerous seductress, etc.—and how those human stories are misinterpretations and caricatures of these living seal-people. She lives on that line between ocean and sky—a perspective that influences her role as storyteller, journalist, activist, truth-teller, artist. She’s experienced loss and cruelty and disrespect, but is still open to all the beauty and hurt in the ocean. I like her a lot.

I like them both a lot. And the two characters both took shape probably from my own heart-weary observations of political divisiveness and interpersonal miscommunications and wondering what would it take for characters from seemingly entirely different worlds to realize they’re a part of the same world, because that’s what’s required for them to save it. So I worked on making their perspectives as different from each other’s as possible: One is inadvertently selfish, the other instinctively altruistic. One expresses herself through songs that can travel through time, the other doesn’t make a sound, etc. Their points-of-view are entirely understandable through what they’ve experienced and been exposed to, and then the story shows the not-always-comfortable process of expanding their understandings of each other and their place in the world.

Mary: Reading this tale brought me closer to the ocean, something I’ve been mesmerized by all my life. Reading this does immerse the reader into the magic, depth, and mysteries of ocean life. Descriptions are often song-like and poetic. I think after reading, I just wanted to go for a swim in a place where I could find a fabulist treasure! But there are also some concerns the characters have, mostly about how climate change is affecting seas around the world. What are some of these issues? How did you research them?

Rae: I didn’t really have to research any of the climate issues affecting the oceans to write this. Rising temperatures, disrupted ocean currents, overfishing, and microplastic pollution. It’s all stuff everyone already knows—and it’s all there in the background as part of the setting like climate disasters are in the background of our lives now (if we’re lucky)—but I think what I wanted to get at with the story was how to get all this information we already know to mean something. I was going to say to make people feel it, but I think most people already do? Say “ocean acidification” and people shut down, not because they don’t care, but because it hurts! It does hurt. It’s a wince and a protective response. I feel like even people super engaged in climate issues and devoted to finding solutions tend to shy away from the enormity of the threats to the ocean. Kind of like, “oh yeah, but the ocean? That’s doomed.” And it can’t be. It’s the world’s largest ecosystem. It can’t be written off as a lost cause.

So I guess my feeling is that “climate communication” problem isn’t trying to get people to care about the climate anymore, I think people care a lot but that most people are really bad at processing grief and painful emotions. Myself included. I am most people. Anger is an easier emotion for me and I’ve embraced climate anger to keep me focused and active, but I know I’ve only got a thin calcified shell keeping me from feeling all of it, and once the CO2 saturation levels eats through that shell, it’s donezoes for me. See, I’m joking it off. Trying to keep it over there. But for me this story was a way to make it possible, to let things sink in. To process what we all already know about the ocean.

So the climate threat that the characters have to deal with is more metaphorical. It has a lot of the big, overwhelming qualities of our less-metaphorical climate threats, and a lot of the same causes… but hopefully looking at the problem removed a few steps will help us see the big spiraling pattern shapes. That it’s not just a technical band-aid for this and this and this thing that we need to come up with. It’s, yeah, probably a shift in worldview? And I know it’s a common platitude to say that the hardest thing to do is change someone’s mind, or go against “human nature,” or enact cultural change. But I don’t believe that. Culture changes all the time. The current way of life certain people in power are whining about being impossible to live without didn’t even exist thirty years ago. So aside from being more specific about the problem—like altering the perception from “man-made climate change” to “industry-driven climate collapse” for example—I hope that opportunities to get a wider view of what we’re facing through thought experiments like Weird Fishes will help get us past that overwhelming, suffocating feeling enough to work the problem.

Mary: Some content warnings precede the story. Do you want to talk about these?

Rae: Sure. One element of the story describes Ceph’s discomfort when she leaves her home environment where nothing threatens her, she experiences a physical discomfort of being out of her depths and exposed to things her position in the deep protected her from.

When I wrote the Author’s Note in the review copy, the audience I had in mind were people who have already lost a lot due to colonial aggression and ecosystem collapse. Kind of “if you were vulnerable to this before, warning, you’ll see it happening here in the story”. But some reviewers who hadn’t had previous experience with sensitive material were finding themselves upset by some content they didn’t usually have a problem with. And I had a hard time knowing how to address that. Part of me was like…good? A strong emotional reaction to something terrible is not a bad thing? Reports of readers consuming the violence numbly would’ve been more disturbing to me. But I’ve changed the Author’s Note in the final version to also address those concerns because I didn’t intend for the inclusion of a certain scene to overshadow the true ending of the story.

I can address it more clearly without spoiling too much: There’s a difficult scene near the end where “the state” retaliates against Ceph’s climate activism in a way that violates her bodily autonomy. It’s not graphic or gratuitous, but there are terrible consequences for the character, so, yes, it’s intense. The scene was included to show how the comforts of Ceph’s society must be consistently maintained by violence. It’s not the first instance where that relationship is shown in the story, but it might be the first time some readers notice it—probably because it affected a character they relate to, maybe the first time they experienced that power dynamic happening to them. Those readers who are already aware of police forces and governments attacking water protectors or killing Indigenous peoples of the Amazon maybe weren’t as surprised to see where the story was going, but some readers felt like it came out of nowhere or was unrelated to the plot, and I have to admit that I didn’t anticipate that it would come as such a shock since I thought there were indications throughout the narrative giving clues where we were headed.

It’s interesting because there is a narrative theme about avoiding painful emotions, and not recognizing “the water” all around us. I’m proud of the readers who experienced a strong emotional reaction—at any point in the story—that they let themselves get deep enough into the story and character to feel something. I get that readers may initially be upset with me for making them feel a way—blaming me as the storyteller and the narrative choices I’ve made for the uncomfortable emotions they’re experiencing—but ideally, I’d like for those readers to be able to focus that feeling of betrayal on what that scene in particular was meant to describe. The “invisible” violence that maintains a cultural dominance. I’ve called this story an extreme exercise in empathy. Sometimes it stings. Sometimes it aches when a muscle gets a work out. I know I’m asking readers to lift some heavy shit, but I promise your compassion muscles are going to get absolutely ripped!

Mary: I wholeheartedly agree! What are some of your own favorite experiences around oceans?

Rae: I grew up in Santa Cruz constantly being cautioned not to play in the undertow—and my memories of the beach are overcast mists obscuring the horizon and the sensation of the tide grabbing the sand out from under my feet, trying to pull me in. Ominous.

Weird Fishes is a love letter to the Pacific Ocean, but I don’t have particularly romantic feelings about the sea. It’s a sense of respect that kinda borders on fear. I’m not afraid of what could be lurking in its depths or whatever, but the pure pounding power of it? No thanks. I’ll stay on the shore barely making eye contact with the waves. I don’t like putting my head underwater and feel an expansive panic at the thought of being on a boat in the open ocean with no land in sight. Yikes. Tsunamis are probably my greatest irrational fear since that’s like… the ocean coming to get me when I’m all the way over here. Even when I’ve stayed a respectful distance away. No escaping its embrace.

I do have a feel-good ocean experience though. When my daughter saw the Pacific Ocean for the first time. She was five or six and had never experienced the sight or sound of intense, crashing waves. I remember holding onto her as we stood in the surf, watching the waves break one after the other, and feeling a jolt of electricity through her body. Just pure muscle-tensing excitement. She laughed louder than the ocean roar. I can still feel her squirming in my arms while I tried to hold her back from running right into the water. That’s my favorite ocean memory. The exhilaration that I got to experience from seeing the ocean through her eyes.

Mary: I love the picture you sent of that moment! Are you working on anything else right now?

Rae: Yes! Right now, I’m finalizing a short story with the team at Khōréō magazine for their March 2023 issue. It’s called The Field Guide for Next Time—a solar-punkish, Indigenous Futurismy, eco-anarchist guidebook for how to live in a speculative future. I’m really proud of all the things I was able to weave into that story—the scope of it in so few words. I’m really really excited that this one will be available for people to read soon.

I’ve also started story research for a project that incorporates those time gyres introduced in Weird Fishes. Kind of a time-travel, sea-faring adventure inspired by the Portuguese side of my family who migrated by boat to work on plantations in Hawaii. I’m thinking it’ll have a Becky Chambers-ish spaceship ragtag crew-family vibe. Space opera on the sea, with characters navigating through time to sabotage “conservation” expeditions in attempts to save island species from extinction. Explore the roots of capitalism in the clear-cutting of Madeira, the harvesting of koa wood in Hawaii, the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. And whaling, venture capitalism was invented to finance risky and expensive whaling expeditions. Difficultly level is set high for me on this one since I’m much more comfortable writing about futures than the past. And boats, ugh. But I can see the finished shape of novel and it’s really fun so I’m going to have to go through the drudgery of writing it. I don’t think this will be one that flies through my fingertips.

Mary: I’m just now reading Becky Chambers’ Monk and Robot books and love it. Your new projects sound wonderful. Let’s definitely keep in touch, and thanks so much for your fascinating new novel and time spent talking with me.

About the Author

Rae Mariz is a Portuguese-Hawaiian speculative fiction storyteller, artist, translator, and cultural critic. Her writing inhabits the ecotone between science fiction and fantasy, often featuring Diasporic Futurisms that draw on her connections to the Big Island, the Bay Area, and the Pacific Northwest. She is the author of the YA sci-fi The Unidentified (2010), the climate fantasy Weird Fishes (2022), and many works of narrative non-fiction in between. She lives in Stockholm, Sweden with her long-term collaborator and their best collaboration yet. Find her work at raemariz.com and on Twitter @raemariz.

Rae Mariz is a Portuguese-Hawaiian speculative fiction storyteller, artist, translator, and cultural critic. Her writing inhabits the ecotone between science fiction and fantasy, often featuring Diasporic Futurisms that draw on her connections to the Big Island, the Bay Area, and the Pacific Northwest. She is the author of the YA sci-fi The Unidentified (2010), the climate fantasy Weird Fishes (2022), and many works of narrative non-fiction in between. She lives in Stockholm, Sweden with her long-term collaborator and their best collaboration yet. Find her work at raemariz.com and on Twitter @raemariz.