Click here to return to the world eco-fiction series

About the Book

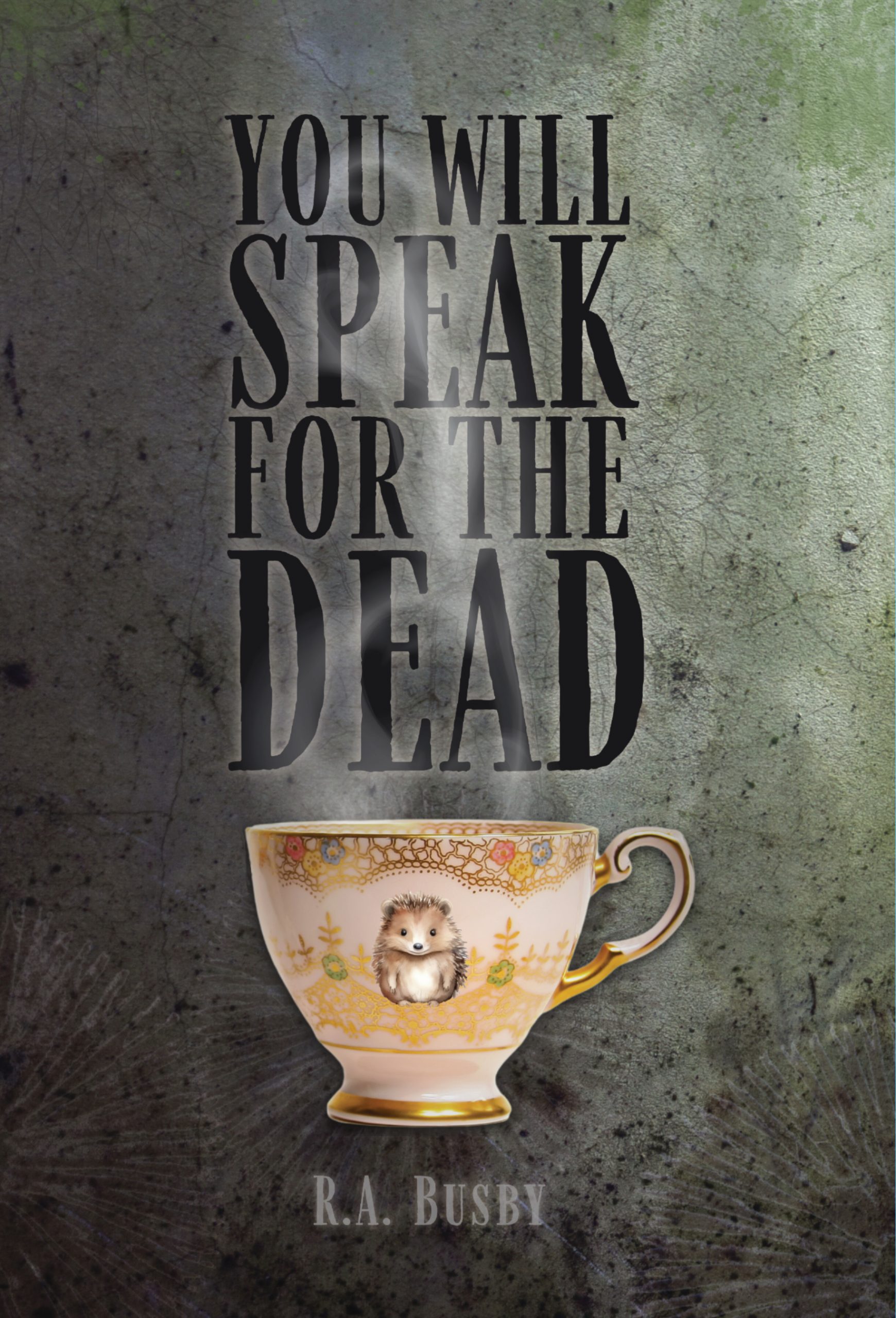

You Will Speak for the Dead (Stelliform Press, 2024), is a transformative body horror novella from Shirley Jackson Award winning author R.A. Busby. Paul Simard’s life is a mess. When his mother dies, and his boyfriend moves out, the only thing Paul has left is his hoarder house cleaning business, and that’s not exactly a recipe for dating success. But after Paul gets a call to clean out the home of some elderly biologist, nothing will ever be the same. You see, 928 Avirosa isn’t just your normal cleanout. Something in the house is…alive. It’s not just the fungal carpet or the mushrooms growing over every surface, or even the disturbing smell. It’s the woman’s voice he hears inside his head. The creeping sense he’s been invaded. The powerful connections to memories and people he’s never seen. Yes. Something in that house is alive. And it wants to speak to him. Before long, Paul understands the house hoards more than just secrets—and Paul’s life depends upon uncovering its answers.

Chat with the Author

Mary: I’m curious about how you began writing this beautiful story and if anything surprised you along the way?

RA: A lot of times, a story will begin for me as an image or a voice, and in this case it began with both. I was walking my dog and thinking about the houses I’d lived in, all of which haunt me in one way or another, especially my mother’s house. When she died, my brother and I had to clean it out—a wrenching experience always, because no matter what, you’re confronted with memories. That’s when I flashed on an image of a basement, a dark place crammed to the ceiling with belongings or dirt or maybe both, and out of that darkness, a dead woman’s hand reaching out. The fingers, I thought, would feel dry and brittle—and then would circle around yours.

Who the woman was, why she was there, I didn’t know. What surprised me was this: Though initially I’d thought of that image as ghastly, the more I wrote the story it became evident that it might be horrifying—but it was also a moment of connection. Of linking. After that, the story fell into place because I knew it was going to drive to that moment of horror and union. Around then, I started thinking about who would go down there into that basement and why, and that’s when I started to “hear” Paul talking about his housecleaning business.

Mary: Had you read fungi fiction before, and did it inspire you?

RA: No, but I love the term “fungi fiction” as well as “sporror.”

Mary: The main character Paul just went through a breakup with his boyfriend, and his mother has died as well, so Paul’s headspace isn’t the greatest. But he begins to transform physically and emotionally. I have to say some of that transformation was in the vein of horror, but some was quite funny. Have you done comedic writing before?

RA: Not specifically, but when I’ve experienced emotionally fraught or horrifying moments, some part of me is almost always sitting back and thinking about the mundane practicalities of the situation, and that contrast usually ends up being pretty funny. I’m thinking of the time my water broke in the hallway of the maternity ward, spilling out in a flood onto the tile, and my first thought was, “Oh, shit! CLEANUP ON AISLE FOUR.” I’m sure that’s a defense mechanism, a way to puncture the Pennywise balloon if you will, but at the end of the day, whatever horrible or traumatic events happen to us, we have to deal with them practically. Someone (and thank you, whoever you were) had to wheel a yellow mop bucket down the hall and swab up spilt amniotic fluid, probably muttering, “Christ, not this again.” (And hey, we need to pay those folks more. Just saying.)

So when I was writing about Paul’s Terrible, Horrible, No-Good, Very Bad Morning when he discovers the extent to which he’s really transforming, part of me was imagining the genuine horror of that moment, and part of me was thinking there’d definitely be an aisle four cleanup involved.

Mary: Paul and his team have a job of cleaning out the house of a hoarder whose owner is presumed missing or just gone. One thing I liked was that the book mentioned that hoarded things seemed chaotic to anyone but the hoarder, who might use the mundane to orient themselves in space. I loved that, and the analogy to places is nature orienting us was a plus. Can you talk about that more?

RA: I think it has a great deal to do with loss and memory. I think we all are deeply hit by loss. We usually think in terms of losing a loved one, but there are deeper, sub-surface losses we don’t talk about as much. The loss of a place. The loss of a time to which we can never return. The loss of the person we once were. Those are irretrievable except in memory—or in mementos, icons of the real thing. If you’re hit by loss often enough, or it hits you hard enough, you want to hold on to what you have, to those things that orient you not just in space but in time.

We often forget important things–pin numbers, passwords, birthdays—but our memory of places is astonishingly strong. Decades later we can recall the layout of a house we’ve visited only once, and a memory trick stretching back to ancient Greece involves mentally “placing” things along a well-known route. (It’s how I recall the elements of the periodic table or what I need to get at the supermarket.) The best guess for why we’re great at this is simple survival: we’re descendants of folks who recalled where those acorn-bearing oaks in the forest grew, which arroyo led to the agaves with good starchy roots. Part of remembering who we are is knowing where we are, and I think that’s why many people moved into assistive care often experience a significant cognitive downturn—they’re uprooted and transplanted from an environment they’ve lived in their whole lives. They can’t find their stuff because it’s not in the right place, and as a result, it’s harder to orient themselves in the world…or to themselves.

That’s why it was easy for me to understand the fundamental emotional appeal of hoarding: Everything is there. Everything is where it’s always been, and nothing is lost. Not even you.

Mary: That’s some beautiful stuff right there. Speaking of nature, our connection with it in and outside of fiction is why Dragonfly.eco exists. These connections are interesting, especially in fungi fiction, sometimes called sporror, because fungi itself is amazing and we don’t know everything about its true biodiversity. What got you into including fungi and spores into this novel?

RA: The short answer is Thoreau and a burger.

As I wrote this novella I was thinking, not surprisingly, of decomposition. How it happens, how the stuff of which we’re made breaks down, oozes out, disaggregates into its separate atoms with nothing to hold it together anymore. All the while, I kept recalling that beautiful passage from Henry David Thoreau’s Leaves of Grass in which a child brings the speaker a handful of grass and asks what it is, and one of the his answers is that it is “the beautiful uncut hair of graves.” Then he asks,

What do you think has become of the young and old men?

And what do you think has become of the women and children?

They are alive and well somewhere.

The smallest sprout shows there really is no death,

And if ever there was it led forward life, and does not wait at the end to arrest it,

And ceased the moment life appear’d.

All goes onward and outward, nothing collapses,

And to die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier.

Then that practical part of me piped up and said, “Well, but not on the moon.” Because the moon’s environment is essentially sterile, you could theoretically put a Quarter Pounder next to the plaque commemorating Edwin Aldrin and Neil Armstrong and come back a couple thousand years later to find it blissfully unrotted.

So that’s when I started wondering more about why we decompose at all, or why we become the beautiful uncut hair of graves instead of eternal Quarter Pounders, and that’s when I started finding out about the crucial role of fungi in bacterial decomposition. Without them, we’d be buried in biomass, just like the Earth was after 75% of all animals and plants on it were killed by an asteroid at the end of the Cretaceous Period and for about two years, photosynthesis wasn’t…a thing.

In short, it was a great moment to be a fungus.

And the more I learned about fungi, the more impressed I was at the complexities of the mycelial networks it develops, the possibility that it was itself an intelligent organism that could make deliberate choices, could link its network to the other organisms around it, could pass on information and nutrients like a well-connected neighbor with a casserole. Could learn. Could remember. Could even live forever, provided it had food. You know. Big dinosaurs. Quarter Pounders. Us.

That’s when it became clear what kind of biologist Martha had been—and why that dead hand reaching out became less a moment of horror and more a moment of connection.

Mary: I love that so much. Is there any other fiction that strongly relates to nature that you have read and liked?

RA: Less fiction than nonfiction—Paul Stamets, of course, and Merlin Sheldrake’s Entangled Life, but also Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild and Into Thin Air. And though it’s problematic in several respects, Jean Auel’s The Clan of the Cave Bear was a book I read over and over in my teens because I was fascinated by the characters’ absolutely crucial need to understand and work within the natural world—how to forage for safe food, how to preserve it, how to use plants and fungi for medicinal and culinary purposes, all of which were crucial to our survival as a species.

Mostly, though, it was nature itself that taught me. Growing up in the desert, I didn’t see much fungi unless it was on a plate, so the first time I section-hiked the Appalachian Trail was a mind-blower. Fungus that looked like horse hooves, dead men’s fingers, perfect white parasols, soft sulfur pillows. Astonishing.

Mary: Maybe we’re sisters from another life because, though Entangled Life is on my read list for next year, Krakauer’s and Auel’s books that you mentioned left a mark on me too.

The ending of your novel was epic, and I have to admit I got a little teary at one point but also the finality offered hope and a sort of grand awareness of time and life. Thanks for that great reading experience, truly. Without spoiling, can you tell us why you wanted a positive ending in the space of a lot of dystopian outcomes these days?

RA: I think it again comes down to loss. When one of the pillars of your world is abruptly removed, it’s more than an absence. It’s an un-making. You have to reorient yourself around that loss, recalibrate your world around the void. And even if you wish you could coat the past in amber and preserve it forever, you can’t—and of course, you’re left with the cleanup. You have to go through their things, throw out belongings, scatter the sticks of the fire. In short, you become a kind of fungus. A decomposer.

But what is also true is that nothing is really lost. Nothing. Not one atom. It’s in different forms, different configurations, but all of it is still there. And I find that profoundly hopeful. Thoreau said it best: All goes onward and outward, nothing collapses, And to die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier.

Mary: That’s a good way to say it. Thanks so much, RA. You Will Speak for the Dead was easily my top read of 2024 and up there of my all-time favorite books.

About the Author

Top three writing credits:

- Corporate Body (Cemetery Gates Media / My Dark Library)

- Words Made of Flesh (Cemetery Gates Media)

- You Will Speak for the Dead (Stelliform Press)

Bio: Author of three novellas and winner of the Shirley Jackson Award, R.A. Busby spends her spare time running in the desert with her dog and finding weird things to write about.

Links to Social Media: