Click here to return to the world eco-fiction series

About the Book

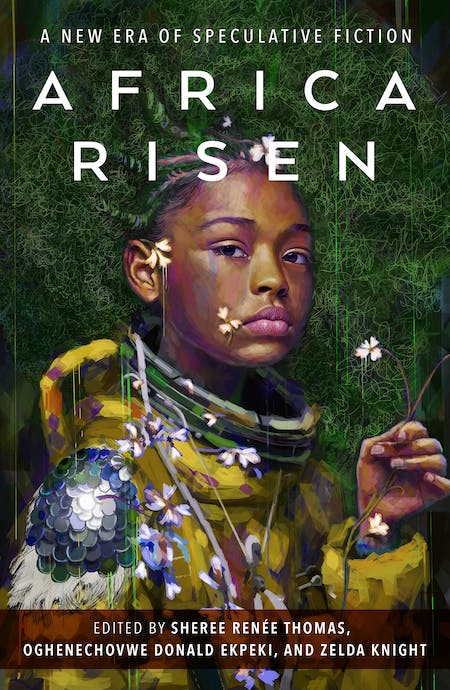

From award-winning editorial team Sheree Renée Thomas, Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki, and Zelda Knight comes an anthology of 32 original stories showcasing the breadth of fantasy and science fiction from Africa and the African diaspora: Africa Risen: A New Era of Speculative Fiction (Tordotcom, November 2022). This month we talk with Sheree, Oghenechovwe, and Zelda about their experiences working together to create this anthology as well as their seminal work to help raise Black speculative fiction voices and stories. Created in the legacy of the award-winning anthology series Dark Matter, Africa Risen celebrates the vibrancy, diversity, and reach of African and Afro-Diasporic SFF and reaffirms that Africa is not rising—it’s already here.

From award-winning editorial team Sheree Renée Thomas, Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki, and Zelda Knight comes an anthology of 32 original stories showcasing the breadth of fantasy and science fiction from Africa and the African diaspora: Africa Risen: A New Era of Speculative Fiction (Tordotcom, November 2022). This month we talk with Sheree, Oghenechovwe, and Zelda about their experiences working together to create this anthology as well as their seminal work to help raise Black speculative fiction voices and stories. Created in the legacy of the award-winning anthology series Dark Matter, Africa Risen celebrates the vibrancy, diversity, and reach of African and Afro-Diasporic SFF and reaffirms that Africa is not rising—it’s already here.

In the book’s introduction, we’re told: “As the origin of humanity and home to the world’s oldest civilizations, Africa is the origin story of storytelling.” For anyone into reading stories set around the world, this is such a powerful statement and propelled me to read more (as if the beautiful cover alone hadn’t already impressed me to discover the stories inside the book). I wanted to find out more about how Africanfuturism, Africanjujuism, and Afrofuturism stories had evolved from the beginning to now. And I wanted to particularly explore with the authors how climate and ecological concerns are addressed in this anthology.

Short story authors: Dilman Dila, WC Dunlap, Steven Barnes, Joshua Uchenna Omenga, Russell Nichols, Nuzo Onoh, Franka Zeph, Yvette Lisa Ndlovu, Wole Talabi, Sandra Jackson-Opoku, Aline-Mwezi Niyonsenga, Alex Jennings, Mirette Bahgat, Timi Odueso, Maurice Broaddus, Tlotlo Tsamaase, Tobias S. Buckell, Somto Ihezue Onyedikachi, Tananarive Due, Ytasha Womack, Oyedotum Damilola Muees, Alexis Brooks de Vita, Tobi Ogundiran, Moustapha Mbacké Diop, Akua Lezli Hope, Mame Bougouma Diene, Woppa Diallo, Shingai Njeri Kagunda, Ada Nnadi, Ivana Akotowaa Ofori, Chinelo Onwualu, Danian Darrell Jerry, Dare Segun Falowo

Chat with the Editors

Mary: Tell us about yourself and the writing you’ve done.

Oghenechovwe: I am an African speculative fiction writer, editor and publisher. I recently completed the first draft of my novel, and it’s still in the editing phase. I do however have short stories out. My latest, Destiny Delayed was published in Asimov’s and reprinted in Galaxy’s Edge and Apex. It’s being translated to Chinese, to appear in Science Fiction World. Destiny Delayed, amongst other things, is a metaphor for climate change and how we mortgage the destinies of children and future ones for profit today. You can read it, and listen to it here.

Zelda: Hello, I’m Zelda Knight. I’m a USA Today bestselling author of steamy romance, British Fantasy Award-winning, and NAACP Image Award-nominated editor as well as a diverse bookseller. I write romance across the spectrum, both sexual orientation-wise and genre.

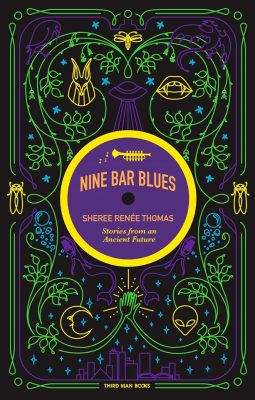

Sheree: My work, particularly the collections Nine Bar Blues: Stories from an Ancient Future, Sleeping Under the Tree of Life, and Shotgun Lullabies, is inspired by myth and folklore, music, natural science, and the genius of the Mississippi Delta culture and conjure. I write in all genres, but my imagination is most often drawn to speculative fiction—stories that walk the blurred lines of fantasy and science fiction and horror. Earth magic and folklore, natural science and music, all of those interwoven threads come from observation, faith, and practice. From being a witness to the magic of the world, the power of words, and the way our stories—even the oldest ones—still linger with us and impact our psychology. I come from a spiritual people of deep faith and a lot of dark humor. That’s how we survived the traumas and a nightmarish history in this world. But there was always light. Sometimes that was expressed in the church, and sometimes that was expressed elsewhere, in the world and in the art, and just in living. That’s how we are surviving them today. I’m a native Memphian, so the city, its many tongues and histories, are part of that tradition and that creative spark. I am intentional in calling upon those layers of culture, because I think so often, particularly in publishing, there is a tendency to try to flatten what it means to be Black, how it sounds, and who gets to be the heroes in their own journeys. I want some of those people who don’t often get to see themselves represented in literature to be seen and heard. Representation is not just about the future, but it is about recognizing the magic and the complexity of life as we know it now.

Sheree: My work, particularly the collections Nine Bar Blues: Stories from an Ancient Future, Sleeping Under the Tree of Life, and Shotgun Lullabies, is inspired by myth and folklore, music, natural science, and the genius of the Mississippi Delta culture and conjure. I write in all genres, but my imagination is most often drawn to speculative fiction—stories that walk the blurred lines of fantasy and science fiction and horror. Earth magic and folklore, natural science and music, all of those interwoven threads come from observation, faith, and practice. From being a witness to the magic of the world, the power of words, and the way our stories—even the oldest ones—still linger with us and impact our psychology. I come from a spiritual people of deep faith and a lot of dark humor. That’s how we survived the traumas and a nightmarish history in this world. But there was always light. Sometimes that was expressed in the church, and sometimes that was expressed elsewhere, in the world and in the art, and just in living. That’s how we are surviving them today. I’m a native Memphian, so the city, its many tongues and histories, are part of that tradition and that creative spark. I am intentional in calling upon those layers of culture, because I think so often, particularly in publishing, there is a tendency to try to flatten what it means to be Black, how it sounds, and who gets to be the heroes in their own journeys. I want some of those people who don’t often get to see themselves represented in literature to be seen and heard. Representation is not just about the future, but it is about recognizing the magic and the complexity of life as we know it now.

And in that magic, there’s a sense of greater things, definitely more powerful than we as a species may ever truly understand, but the mystery won’t stop us from trying to do so. It’s that mystery and magic, that weirdness that makes me curious, and it’s something I lean into and explore when it feels right. Backsliders and Scripture-quoters, the let-it-be-what-it’s-gon’-be folks, all of those ways of seeing and being are important in recreating or reimagining the world on the page. There’s something powerful and frightening in all of it, in the old haints and too-horrible-but-it’s-true tales that my grandfather and his friends and neighbors would share. I think it’s no coincidence that the Black horror we are seeing today explores how the very act of us existing is often the source of the horror. We are both hypervisible and invisible at the same time. Blackness in these films and series is the catalyst, the motivating force and that’s been true in more ways than we like to tell, but that’s the real scary stuff. Beacons in the journey included Zora and Walker, Morrison and Jones, Dumas, Reed, Baraka and Bradbury, Garcia and Rushdie, and more recently, the films of Jordan Peele, so many writers whose writing transported me, and continue to spark my imagination.

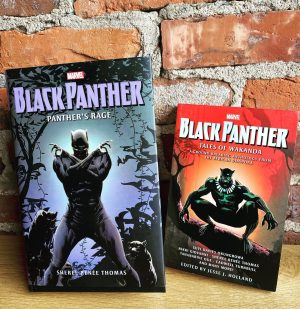

Adapting the legendary Black Panther comics from the original Don McGregor, Rich Buckler, and Billy Graham series was quite an honor and a challenge. Black Panther: Panther’s Rage was my first novel, and I was asked to cover the Panther’s Rage arc, roughly thirteen separate issues that introduced not only the iconic Killmonger character but so many of the Black Panther’s villains. Because of Christopher Priest and Reginald Hudlin’s wonderful creations of Shuri and the Dora Milaje, there was an incredibly rich world for me to explore. My first goal with the novel was to honor the original work. As a fan of the comics, I know that McGregor’s writing is foundational, and there are certain things that those who are versed in the comics will expect and be looking for. Some of those key moments were adapted in the first Marvel Cinematic Universe movie, which has its own, different storyline, but there were changes to some core characters in the movie and that just isn’t the case for the comics canon. For example, Monica Lynne, the only other African American character in the arc, besides Killmonger, was not featured in the movie, and Nakia, who is a villain in the comics, was changed in the movies to become T’Challa’s love interest. As a novelist, my goal was to reimagine Monica as a character and to update the work so that it speaks to a 21st century audience. Wakanda is far more visible and technologically advanced, and T’Challa is more than a chief of a smallish village; he’s the political and symbolic head of a self-reliant empire. I wanted to create a space for those who may know very little about the Black Panther comics and for those who entered the fandom through the films. It was an interesting challenge to adapt some of the beautiful, amazing art and bring its spirit into prose. A novel is not a comic book, and neither of those mediums are movies. They are their own separate forms with their own aesthetics. I had a great time writing the novel, which required me to reread the comics and much of the ancillary works, and I hope readers enjoy getting a sense of T’Challa as more than just a figurehead in an amazing costume. He’s not just a superhero, and he’s not an infallible god. He’s a grown man, an Oxford-trained physicist, who is grieving and trying to build a life and make sense of himself after having quite clearly abandoned his post as the leader of Wakanda. His choice to fight with the Avengers left space for new enemies to emerge and wreak havoc in his homeland. Of course, if T’Challa was perfect and could foresee so much, we wouldn’t have a story or any of the comics, because he would have already known not to trust N’Jadaka aka Killmonger. But T’Challa is mortal, a human, and even everyday humans have egos, hubris, and flaws. Both Killmonger and T’Challa are arrogant men who feel like they can back it up. T’Challa has to recognize his own shortcomings before he is able to fight this world-changing battle that threatens Wakanda and everyone he knows and loves. Monica Lynne, his team, and in fact, the citizens of Wakanda help him achieve that.

Adapting the legendary Black Panther comics from the original Don McGregor, Rich Buckler, and Billy Graham series was quite an honor and a challenge. Black Panther: Panther’s Rage was my first novel, and I was asked to cover the Panther’s Rage arc, roughly thirteen separate issues that introduced not only the iconic Killmonger character but so many of the Black Panther’s villains. Because of Christopher Priest and Reginald Hudlin’s wonderful creations of Shuri and the Dora Milaje, there was an incredibly rich world for me to explore. My first goal with the novel was to honor the original work. As a fan of the comics, I know that McGregor’s writing is foundational, and there are certain things that those who are versed in the comics will expect and be looking for. Some of those key moments were adapted in the first Marvel Cinematic Universe movie, which has its own, different storyline, but there were changes to some core characters in the movie and that just isn’t the case for the comics canon. For example, Monica Lynne, the only other African American character in the arc, besides Killmonger, was not featured in the movie, and Nakia, who is a villain in the comics, was changed in the movies to become T’Challa’s love interest. As a novelist, my goal was to reimagine Monica as a character and to update the work so that it speaks to a 21st century audience. Wakanda is far more visible and technologically advanced, and T’Challa is more than a chief of a smallish village; he’s the political and symbolic head of a self-reliant empire. I wanted to create a space for those who may know very little about the Black Panther comics and for those who entered the fandom through the films. It was an interesting challenge to adapt some of the beautiful, amazing art and bring its spirit into prose. A novel is not a comic book, and neither of those mediums are movies. They are their own separate forms with their own aesthetics. I had a great time writing the novel, which required me to reread the comics and much of the ancillary works, and I hope readers enjoy getting a sense of T’Challa as more than just a figurehead in an amazing costume. He’s not just a superhero, and he’s not an infallible god. He’s a grown man, an Oxford-trained physicist, who is grieving and trying to build a life and make sense of himself after having quite clearly abandoned his post as the leader of Wakanda. His choice to fight with the Avengers left space for new enemies to emerge and wreak havoc in his homeland. Of course, if T’Challa was perfect and could foresee so much, we wouldn’t have a story or any of the comics, because he would have already known not to trust N’Jadaka aka Killmonger. But T’Challa is mortal, a human, and even everyday humans have egos, hubris, and flaws. Both Killmonger and T’Challa are arrogant men who feel like they can back it up. T’Challa has to recognize his own shortcomings before he is able to fight this world-changing battle that threatens Wakanda and everyone he knows and loves. Monica Lynne, his team, and in fact, the citizens of Wakanda help him achieve that.

Mary: From the get-go I just loved the introduction and the first story, “The Blue House”, but really, this anthology did not have just one-hit wonder. It was an album of greatest hits, with a stunning cover to boot. So congrats on that. It seems like the range of speculative fiction in this anthology is diverse and deals with everything from hard sci-fi, fantasy, diaspora, mythology, climate change, alternative history, and even some solarpunk thrown in. As a reader interested in fiction from around the world, and about our current ecological demise, I’ve found the experience of reading African stories engaging and something to learn from. I also liked what the introduction says about Africa being the first place that “humanity first sought to make sense of our world, the cosmos above, the natural flora and fauna below”.

What do you think readers will learn from Africa Risen? How did you get involved with Africa Risen, and what was it like working with the other editors?

Oghenechovwe: I think readers will learn about the far ranging and wide scope of African speculative fiction and writers. Also the strength of our literature. That it is not rising, but already here. Hopefully, they will also take advantage of the wealth of new writers introduced there and seek them out, to immerse themselves further, in their expansive worlds.

I am one of Africa Risen‘s co-editors and came together with Sheree Renée Thomas and Zelda Knight to edit the anthology and give it the wide berth and perspective it has. Working with Zelda and Sheree was interesting because they have different backgrounds, preferences, and tastes. Blackness as you know, is not monolithic. This lends itself, after we learn to trust those differences, to a body of work that is diverse and far ranging, showcasing a depth and breath we wouldn’t have accomplished otherwise.

Zelda: All that you wrote and so much more! I think one thing that comes with diversifying your shelf is a more globalized understanding of how our world came to be. And, even in the most depressing read, how we can still overcome and create a more equitable and just future. By showcasing a broad range of storytelling, readers will come away with more thought-provoking questions. And that’s why I think it’s so important for genre anthologies not to print stories that almost read like carbon copies of the “theme” or of each other. Some stories are in conversation, on purpose. But my hope is that no reader comes away feeling the same way.

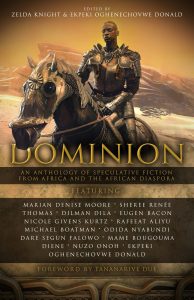

Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki approached me to join as a co-editor around the time the anthology concept was pitched to Tordotcom. We had worked together before on Dominion, so I was excited about another opportunity to work with African authors and authors in the diaspora. And, of course, the wonderful Sheree Renée Thomas! It was truly an amazing and sometimes stressful opportunity! Co-editing with Oghenechovwe was a brand new experience as I’ve always solo-edited before. And then balancing the likes, dislikes, wants, and needs of two more co-editors at the same time kind of compounded the good and the bad. But there was much more good than bad, I would say, and Africa Risen really shines because we all collaborated together. Similarly, wrangling 33 authors through revisions, audiobook pronunciation guides, etc., was a challenge, but overall it was a fulfilling adventure I’ll never forget.

Sheree: The response to Africa Risen: A New Era of Speculative Fiction has been so exciting! We were fortunate to receive story submissions from throughout Africa and her diaspora, and as a reader combing through those stories, it was a full, sensory experience entering so many different imaginary worlds told in ways that weren’t all traditionally Western-centered. I think that is the sense of discovery that readers are going to take away with them after they finish the anthology, that and the fun of being introduced to new writers that they’ll hopefully continue to read and support in the years to come.

Oghenechovwe and I talked about the controversies around the concept of “Africa rising”, as if original, exciting, and worthwhile art wasn’t already being created, so my old title changed from Africa Rising to Africa Risen, and we all set about thinking how we might create a new space for original stories by writers in Africa and her diaspora to be collected. Zelda is so impressive, in that Dominion came out of her heart and her work as an independent publisher with a considerable list of authors. Oghenechovwe understood how historic this work could be and as one of the few writers who lives in Africa and publishes in the genre, he knows how vital this opportunity can be for emerging voices. Having a shared vision is so important, and that has served us well in editing this volume and beating the collective drum to get the word out. I’m so glad you enjoyed the introduction, because we recognized that for linear readers (and those who don’t skip intros), it would be the first opportunity for us to create a larger context for these original stories and to highlight some of the good work in multiple mediums that has been going on for years.

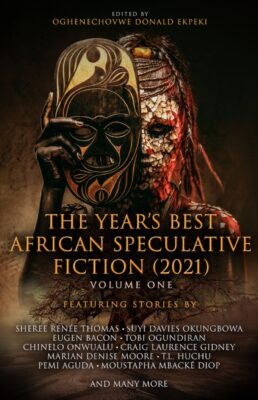

I had the opportunity to review Oghenechovwe and Zelda’s first anthology, Dominion, for Asimov’s, and while I wasn’t able to discuss all of the stories I loved, I was able to highlight a few of my favorites. Besides the exciting cover art, the anthology featured so many writers whose work was new to me and it reminded me of the excitement I felt when I first began editing Dark Matter all those years ago. OG and I talked a lot, from the Obsidian Voices virtual gatherings and on, and one thing we talked about was how my original wish for the first volume of Dark Matter was to include more African writers, and how difficult it was to just have the SFF community even be aware that more than two or three Black writers actually read and wrote in the genre at all. Originally I wanted the third volume of Dark Matter to include a lot of African writers and its working title was Africa Rising in the call for submissions, but I stopped working on it when I began seeing more books and anthologies being published by Africans themselves, so to me, it seemed like that moment had passed and the work was being done.

Mary: Oghenechovwe and Zelda, can you tell us more about Dominion? How do these projects compare?

Oghenechovwe: With more editors, and the experienced hand of Sheree Renée Thomas guiding it, the wings of the Dark Matter anthology covering it, I’d say it’s a more expansive and immersive body of work. A full realization of the potential the Dominion anthology promised.

Zelda: So, Dominion was a concept I came up with shortly after a house fire and around the time of the 1619 memorials here in the United States. I asked Oghenechovwe to co-edit as I had published one of his short stories, really liked his writing, and thought it fitting that an editor on the continent and in the diaspora work on Dominion. You’ll see a lot of the same themes in Dominion echoed in Africa Risen for various reasons, but I think Africa Risen is more expansive. On one hand, it’s just a girthy book! But, on the other hand, I think Africa Risen does an even better job showcasing the breadth and depth of Black storytelling traditions.

Mary: Sheree, Can you talk more about Dark Matter?

Sheree: With Bram Stoker Award and Pulitzer Prize winners, National Book Award finalists, and too many other honors to name, Dark Matter’s contributors have gone on to make history in so many ways, and it has been a joy to see, as many weren’t well-known voices in the field at the time of publication on July 1, 2000. I was just thinking about how contributor Pam Noles impacted the creation of Lovecraft Country or how others in the book have gone on to inspire so many writers we love today.

It’s been twenty-five years since I started the research that would become Dark Matter. And while the Dark Matter anthologies weren’t my first publishing experiences—I’d already published Anansi: Fiction of the African Diaspora, in 1999, a literary journal in trade paperback—to say I foresaw any of the significant changes that have now become part of our field would be disingenuous. I knew that the work of excavation was vital and that the stories and writers were there, but I did not know how it would be received or what communities would spring up from the space we created.

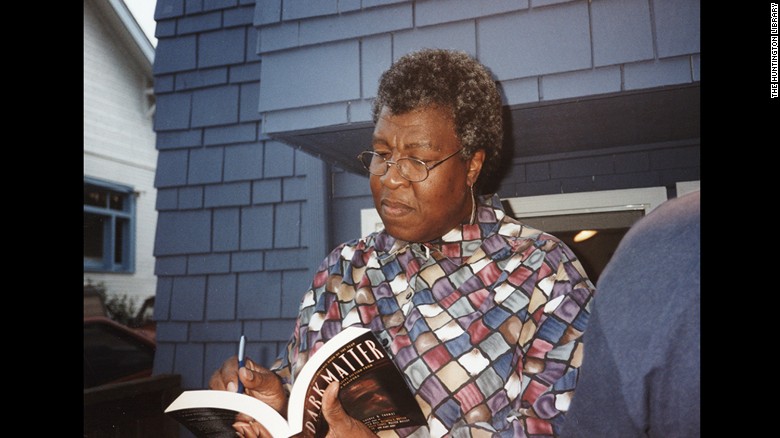

Like many of the writers in the anthologies—Samuel R. Delany, Ishmael Reed, Walter Mosley, Steven Barnes and Tananarive Due, Kalamu ya Salaam, and the late Amiri Baraka, Wanda Coleman, and Charles R. Saunders—Octavia E. Butler was very supportive of the anthologies and the contributors to both volumes, Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction from the African Diaspora and Dark Matter: Reading the Bones. We’d met several times before I pitched the then unnamed anthology to her and before I would study with her at Clarion West in ’99. I’d interviewed her at a standing-room-only gathering at Yari Yari. She’d told me that she and Martin Greenberg had tried to publish an anthology, but were told by publishers that “no one wanted to read a book about race.” We’d talked about how the very act of creating stories with Black characters as protagonists, the heroes in their own adventures and journeys, was perceived as being inherently political, making the entire work for some readers—and publishers—”about race.”

It was a frustration that Butler, of course, handled graciously, by continuing to write kick-ass novels and stories that quieted that noise. The work was the work, and she did it masterfully. Knowing she still chose to people her stories and the worlds she created with not only Black women characters, resilient, caring, and sensible like the women in her family, but with diverse communities who faced extraordinary challenges, was important to see, and it made me appreciate the possibilities that a collection like Dark Matter could open up for everyone.

I was thrilled and not surprised to see other communities beginning to publish their work as well. Several volumes came out in addition to the delicious litany of Dark books. I think on these shores, Black people are used to opening doors that are closed to them, by symbolic force and sheer necessity—we’re trying to live and prosper as well, you know—and when we break down those doors, everyone and their mama comes through right with us. Has it ever been different?

So here we are. Now everyone discusses W. E. B. Du Bois’s work as science fiction—first introduced in the Dark Matter anthologies. And there isn’t this assumption that Black writers don’t exist in the field beyond the two or three people could name at the time. We have long been here, and if you actually thought about it, you could have easily named many other fine writers and added them to the lists of those who create speculative fiction.

It’s a thrilling contribution that never stops feeling new to me, because I remember the blank stares and the dismissiveness that came when people learned I was interested in science fiction, and in those early days, sometimes, even more so coming from someone non-white. Some things have changed wonderfully, and some things remain the same. It’s cyclical, but with each round of negotiations and innovations, we get a little closer to being able to experience this field and the publishing industry the way other writers do.

It’s always been about perception—who is perceived as being ‘universal’ or ‘present’ (thank goodness we no longer have to debate about mere existence, as in, “do Black people read and write science fiction? I dunno!”). It’s always been about who is ‘valued’ and what stories are worth supporting, worth being told. We didn’t have a Fiyah Magazine then—so if your stories were perceived as too Black or too extra or whatever, you were ass out, ha ha! We didn’t have the kind of social media we live and breathe today. So, community-building and even visualizing a possible critical mass was really hard. People weren’t yet fully comfortable with reading and publishing short fiction online. Digital books weren’t even part of the publishing boilerplate back then. Strange Horizons was first published two months after the first volume of Dark Matter appeared in hardcover. It was an exciting time full of possibility. None of us knew what the future might hold, but we were hopeful, and it feels like we are in the midst of that kind of change again.

Mary: In speculative fiction, have you read a lot of environmental subject matter, including anything from biodiversity and mythology based upon the natural world and contemporary issues such as climate change? And, do you see a rise in this fiction from Black writers?

Oghenechovwe: I do indeed see a rise in fiction about biodiversity and the environment, as more African writers find the avenues to address these topics, which they have been concerned about for a while. Several of the works in the Africa Risen anthology address that. From “Mami Wataworks” to “Cloud Mine” and others.

Zelda: Yes, I have for some time. When I was still running the quarterlies Helios and Selene (which will soon be online for free over at azkstudios.com), I received a decent amount of submissions that fell under what was starting to be called “climate fiction.” Now SFF writers have been writing climate fiction for some time; Ursula K. Le Guin comes to mind. But there started to be this movement towards branding it and also writing more positive futurism like solarpunk. Ecologist Nina Munteanu did a guest blog post on my website back in 2019 on the topic entitled “Investing in The Future by Embracing (Climate) Change.”

I personally wouldn’t say there’s a rise in this type of fiction from Black writers, but the broader genre has just been present and not explicitly named. Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler is an example I think many would point to as a foremother. Sherri L. Smith’s Orleans is another I can think of off the top of my head tackling environmental racism when it comes to hurricanes in a speculative setting. Of course, I’ve also published/edited a few pieces I would call Black CliFi (to an extent). In Dominion, “The Satellite Charmer” by Mame Bougouma Diene and “Ife-Iyoku, the Tale of Imadeyunuagbon” by Oghenechovwe would fall under climate-conscious fiction (both stories wrestling with the ecological fall out of geopolitical machinations). And, in Africa Risen, I would definitely include “Mami Wataworks” by Russell Nichols and “Cloud Mine” by Timi Odueso, tackling drought (among other things).

But, yeah, a long-winded way of saying I don’t really see a rise, more so a claiming of disparate titles under the CliFi banner. It’s been there for quite some time. Now we have better language to classify speculative fiction dealing with, or rooted in, environmental subjects.

Sheree: For the past two years I’ve had the honor to help co-judge the Grist Imagine 2200 Climate Fiction contest. It’s a wonderful speculative fiction contest—no fee required—that invites writers to imagine the next seven generations of healing and community-based climate solutions featuring diverse characters. Winners win cash and publication. Last year’s prompt was “Fiction for Future Ancestors,” and we got a chance to discuss the winning works and the larger themes at the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence. We’re trying to inspire an uprising of the imagination, subverting the traditional tales that treat dystopias as inevitable. Perhaps it’s not an easy challenge when all around us predicts doom and gloom. Getting into a different head space is the perfect prompt for speculative fiction writers who are always working to push the boundaries of what is possible, expanding our ideas of what we can do together as people and good stewards of the Earth. Black communities around the world are some of the ones that are hit the most by climate change. I wrote about this in “Imagination Will Help Find Solutions to Climate Change,” one of my essays for the New York Times on the topic. My story, “Ancestries” from Nine Bar Blues, which appeared in The Year’s Best Dark Fantasy & Horror, and The Year’s Best African Speculative Fiction, is set in a society created in a climate-devastated future. “The Grassdreaming Tree” that appeared in Sleeping Under the Tree of Life, So Long Been Dreaming: Postcolonial Science Fiction & Fantasy, and The Big Book of Modern Fantasy, 1945-2010, featured a planet of Black colonizers who fled climate disasters (and racism). In addition to classic work by Octavia E. Butler and Walter Mosley’s eco-fiction, writers such as Andrea Hairston, N.K. Jemisin, Imbolo Mbue, Tochi Onyebuchi, Tade Thompson, and others are creating works that speak to these concerns while exploring new mythology and ways to examine the environment and biodiversity.

Sheree: For the past two years I’ve had the honor to help co-judge the Grist Imagine 2200 Climate Fiction contest. It’s a wonderful speculative fiction contest—no fee required—that invites writers to imagine the next seven generations of healing and community-based climate solutions featuring diverse characters. Winners win cash and publication. Last year’s prompt was “Fiction for Future Ancestors,” and we got a chance to discuss the winning works and the larger themes at the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence. We’re trying to inspire an uprising of the imagination, subverting the traditional tales that treat dystopias as inevitable. Perhaps it’s not an easy challenge when all around us predicts doom and gloom. Getting into a different head space is the perfect prompt for speculative fiction writers who are always working to push the boundaries of what is possible, expanding our ideas of what we can do together as people and good stewards of the Earth. Black communities around the world are some of the ones that are hit the most by climate change. I wrote about this in “Imagination Will Help Find Solutions to Climate Change,” one of my essays for the New York Times on the topic. My story, “Ancestries” from Nine Bar Blues, which appeared in The Year’s Best Dark Fantasy & Horror, and The Year’s Best African Speculative Fiction, is set in a society created in a climate-devastated future. “The Grassdreaming Tree” that appeared in Sleeping Under the Tree of Life, So Long Been Dreaming: Postcolonial Science Fiction & Fantasy, and The Big Book of Modern Fantasy, 1945-2010, featured a planet of Black colonizers who fled climate disasters (and racism). In addition to classic work by Octavia E. Butler and Walter Mosley’s eco-fiction, writers such as Andrea Hairston, N.K. Jemisin, Imbolo Mbue, Tochi Onyebuchi, Tade Thompson, and others are creating works that speak to these concerns while exploring new mythology and ways to examine the environment and biodiversity.

Mary: What other projects are you working on now?

Oghenechovwe: I have a collection coming soon, a graphic novel, novelettes, anthologies, and my novel I just finished. And a bunch else you’ll just have to wait to see. *smiles*

Zelda: If you’re into romance, especially speculative romance, I’m always working on a new project that you can find on my website authorzknight.com. Editing-wise, I have three anthologies planned for this year: From the Ashes: An Anthology of Elemental Urban Fantasy, FABLE: An Anthology of Sci-Fi, Horror & the Supernatural, and Sovereign: An Anthology of Black Fantasy Fiction. Be sure to support by buying, reviewing, and/or spreading the word for free!

Sheree: I’m entering my third year as the editor of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, founded in 1949, and I’ve had the pleasure of reading a tremendous amount of great work and the honor of publishing some of it in the pages of the magazine. F&SF is that rare print magazine, and we also offer digital editions of each of our six annual issues. For me, it’s like editing six 258-page books each year, and I’m excited that it offers so many different things in addition to the stories and poetry. There’s art and wonderful book reviews and columns that cover TV, film, poetry, industry news and data analysis, and Curiosities. I am also the associate editor of the multiple award-winning Obsidian, founded in 1975 during the Black Arts Movement, and we are so thrilled to publish some of the finest Black writers around the world. This year we were honored with grants from the NEA, the Poetry Foundation, and was named a Firecracker Award honoree.

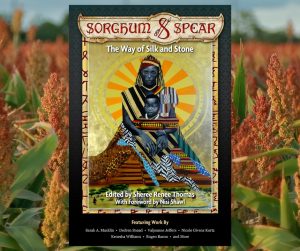

I edited Dedren Snead’s Sorghum & Spear: The Way of Silk and Stone, including work by some fine writers—such as the late Valjeanne Jeffers—with a foreword by Nisi Shawl. I also co-edited Trouble the Waters: Tales from the Deep Blue, with Pan Morigan and Troy L. Wiggins, and have new stories forthcoming in some great soon-to-be-announced books that I can’t wait for you to read. Last year never really felt like it ended, so this year has started off fast to say the least. I just finished teaching a speculative fiction writing workshop for Under the Volcano’s 20th Anniversary in beautiful Tepoztlán, Mexico, with some great writers whose work you will read soon, and I’m presenting a talk on Afrofuturism at the University of Paris, Saint Denis. In March, I will be celebrating in New York City at the National Black Writers Biennial Conference held at Medgar Evers College, where I will be honored with the 2023 Octavia E. Butler Award with one of my favorite authors, Jewell Parker Rhodes. Look for the trade paperback editions of the New York Times-bestseller, The Memory Librarian and Other Stories of Dirty Computer by Janelle Monáe, Alaya Dawn Johnson, Eve L. Ewing, Danny Lore, Yohanca Delgado, and me, featuring the novelette I co-wrote with Monáe, “Timebox Altar(ed)” and Black Panther: Tales of Wakanda, edited by Jesse J. Holland featuring a novelette by me, “Heart of a Panther,” and works by Tananarive Due, Nikki Giovanni, Linda D. Addison, Maurice Broaddus, Christopher Chambers, Danian Darrell Jerry, Milton J. Davis, Kyoko M, Alex Simmons, Temi Oh, Glenn Parris, Cadwell Turnball, Harlan James, L.L. McKinney, Troy L. Wiggins, and Suyi Davies Okungbowa.

I edited Dedren Snead’s Sorghum & Spear: The Way of Silk and Stone, including work by some fine writers—such as the late Valjeanne Jeffers—with a foreword by Nisi Shawl. I also co-edited Trouble the Waters: Tales from the Deep Blue, with Pan Morigan and Troy L. Wiggins, and have new stories forthcoming in some great soon-to-be-announced books that I can’t wait for you to read. Last year never really felt like it ended, so this year has started off fast to say the least. I just finished teaching a speculative fiction writing workshop for Under the Volcano’s 20th Anniversary in beautiful Tepoztlán, Mexico, with some great writers whose work you will read soon, and I’m presenting a talk on Afrofuturism at the University of Paris, Saint Denis. In March, I will be celebrating in New York City at the National Black Writers Biennial Conference held at Medgar Evers College, where I will be honored with the 2023 Octavia E. Butler Award with one of my favorite authors, Jewell Parker Rhodes. Look for the trade paperback editions of the New York Times-bestseller, The Memory Librarian and Other Stories of Dirty Computer by Janelle Monáe, Alaya Dawn Johnson, Eve L. Ewing, Danny Lore, Yohanca Delgado, and me, featuring the novelette I co-wrote with Monáe, “Timebox Altar(ed)” and Black Panther: Tales of Wakanda, edited by Jesse J. Holland featuring a novelette by me, “Heart of a Panther,” and works by Tananarive Due, Nikki Giovanni, Linda D. Addison, Maurice Broaddus, Christopher Chambers, Danian Darrell Jerry, Milton J. Davis, Kyoko M, Alex Simmons, Temi Oh, Glenn Parris, Cadwell Turnball, Harlan James, L.L. McKinney, Troy L. Wiggins, and Suyi Davies Okungbowa.

Mary: Can’t wait to see what’s in store for the future. Thanks to all of you for your time in talking with me, as I know your schedules are so busy. Most of all, thanks for your great passion and the significant roles you’ve played in impelling humanity’s first stories, rising and risen stories, and future stories, into the world.

Bios

Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki is an African speculative fiction writer and editor in Nigeria. He won the Nebula award and is a multiple Hugo finalist. He also won the Otherwise, Nommo, BFA and is a finalist in the WFA, Locus, BSFA, & Sturgeon awards. His fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Strange Horizons, Galaxy’s Edge, Apex, Asimov’s, Tor.com, and more. He edited and published the Bridging Worlds anthology, the first ever Year’s Best African Speculative Fiction anthology, and co-edited the Dominion and Africa Risen anthologies. He founded Jembefola Press and the Emeka Walter Dinjos Memorial Award For Disability In Speculative Fiction. He’s a 2022 Can*Con guest of honour and 2023 ICFA guest of honour.

Zelda Knight is a USA Today bestselling author of steamy romance, British Fantasy Award-winning and NAACP Image Award-nominated editor, as well as a diverse bookseller. She’s also the publisher and editor-in-chief of Aurelia Leo, an independent Nebula Award-nominated press. Zelda co-edited Dominion: An Anthology of Speculative Fiction from Africa and the African Diaspora (Aurelia Leo, 2020), which has received critical acclaim, and Africa Risen: A New Era of Speculative Fiction (Tordotcom, 2022). Keep in touch on social media @AuthorZKnight. Or, visit her website: authorzknight.com. You can also email z@authorzknight.com.

Sheree Renée Thomas is a New York Times bestselling, two-time World Fantasy Award-winning author and editor. A 2022 Hugo Award Finalist, she is the author of Nine Bar Blues: Stories from an Ancient Future, a Locus, Ignyte, and World Fantasy Finalist, Marvel’s Black Panther: Panther’s Rage novel, an adaptation of the legendary comics, and she collaborated with Janelle Monáe on the story, “Timebox Altar(ed)” in The Memory Librarian and Other Stories of Dirty Computer. She co-edited Africa Risen: A New Era of Speculative Fiction, a NAACP Image Award nominee, and is the Editor of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, founded in 1949 and the Associate Editor of Obsidian, founded in 1975 during the Black Arts Movement. Sheree lives in her hometown, Memphis, Tennessee, near a mighty river and a pyramid. Visit Sheree’s website.