This is the 600th book post made in the years I’ve run Dragonfly, and I wanted to make it special on this fifth anniversary. Perhaps this should have been my first post ever, but it took me a long time to come up with a standard for any sort of series, much less a universe of books. My favorite childhood book, The Hobbit, was published 18 days before my avid reader of a father was born. So, unsurprisingly, the book was still very relevant in our house many years later–I can still picture my sweet dad sitting next to a softly lit brick fireplace reading. At first an English major, then a math major, and then with a masters in civil engineering, he was always reading–poetry and fiction his first loves–and the older he got, he’d have to shove the glasses down his nose–refusing to get bifocals. It’s no wonder I developed my love of reading as well as my need for being outdoors, another love of life, encouraged early on and throughout childhood and teen years by both my parents.

I grew up reading books and watching movies from the Middle Earth Universe, but can I post an entire universe within one sitting? Probably not, but I can’t not include it here either. At this site I use metadata under “type” of book–such as novel, series, graphic novel, anthology, ominbus, and so on. For this post I made a new data field: legendarium. I will scratch the surface on the research about how eco-fiction fits Tolkien’s plethora, but don’t expect this post to do much justice to the large, voluminous work from one of my favorite authors nor to the many other papers, blog posts, and news articles written about the essentiality of nature and environmental issues found within Tolkien’s works. Here are a few:

- From the Tolkien Estate: The natural world in Middle-earth is central to Tolkien’s imaginal world. It is not the only thing that matters in that world, of course, but it is an essential part of it…Tolkien’s own love of nature cannot be doubted. His profound feeling for natural place, variety and detail permeates The Lord of the Rings especially, and is an important part of the reasons why it is so convincing. The story takes in geology, ecosystems and bioregions, flora and fauna, seasons and the weather, and the Sun, Moon, planets and stars. Nor – and this is another key point – are these merely a passive backdrop for the human (and quasi-human) drama. Far from it. Middle-earth is an actor, a character, itself, and so are all its important places and parts. Tolkien’s work is not anthropocentric (human-centred).

- From The Trumpeter: In J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, the interrelationships between the natural world and the “Free Folk” (I 367) displays a philosophy similar to those of the person-planetary paradigm and Taoism. Thus, landscape surpasses its traditional role as setting and becomes both the medium and the message of the tale. Because Tolkien’s fiction reflects an environmental philosophy, which is a reflection of his own personal philosophy, The Lord of the Rings is, therefore, an environmental work which addresses the problems of our ever-increasing technocratic society of this, the Fourth Age of Middle Earth.

- Ents, Elves, and Eriador: The Environmental Vision of J.R.R. Tolkien: This is an access-only academic paper via Jstor, written by Matthew Dickerson and Jonathan Evans, published in 2006 by the University Press of Kentucky.

- The Evolution of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Portrayal of Nature: Foreshadowing Anti-speciesism: Another academic paper, this one by Eleanor R. Simpson, published by the West Virginia University Press (2017) via Muse Online. “Some recent scholarship on the work of J.R.R. Tolkien has focused on his attitudes towards the natural world. The memorable character Treebeard and the peaceful pastoral hobbit culture in the Shire are given much attention in establishing Tolkien as an eco-writer. Scholarly interest in environmental themes within his works is justified by Tolkien’s declared intention to “take the part of trees as against all their enemies” (Letters 419). Tolkien’s appreciation of trees permeated his writing and his daily life. He lamented the effects of industry, and proudly offered that he was ‘(obviously) much in love with plants and above all trees’ and found ‘human maltreatment of them as hard to bear as some find ill-treatment of animals’ (Letters 220). “

- J.R.R. Tolkien, ecology, and education: Free access (PDF download). Written by Thad A. Burkhart. Directed by Dr. Glenn M. Hudak, 2015. 205 pp.: This dissertation will prove that the study of Bombadil is a boon to ecological education in the forms of autodidacticism, ecopedagogy, and ecoliteracy by showing readers how the Earth should be treated and with regard to changing our current anthropocentric mindset to one that embraces a respect and reverence for nature; that is, biophilia.

- The Culture of Nature in Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings: Written by Allison Kerley, 2015, Scripps. A thesis paper with free access: I will be analysing two cultures from The Lord of the Rings, by J.R.R. Tolkien: The Ents of Fangorn Forest and the Elves of Lothlórien. Not only do they see nature distinctly from one another, but their relationship to nature isn’t even fathomable within our (Earthly) perspective. Tolkien’s language can give us a sense of how these two cultures of his creation relate and respond to the natural world, but even his reliable narrator is an outside source.

- Representations of Nature in Middle-earth: List of papers/abstracts from Walking Tree Publishers, edited by Martin Simonson (Cormarë Series No. 34), 2015–links to buy books are available at site: All in all, nature in Middle-earth plays a crucial role not only in the creation of atmospheres and settings that enhance the realism as well as the emotional appeal of the secondary world; it also acts as an active agent of change within the setting and the story. This collection of essays explores Middle-earth as an ecological entity, a scene for metaphysical speculation, an arboreal depository of cultural memory and a reflection of real-world natural and imperialistic processes.

From Tolkien, I got not only many enjoyable hours of reading and imagining but also my personal favorite motto: “Not all those who wander are lost.” And references in music–like reading–are so important to me. Led Zeppelin’s classic hit “Stairway to Heaven” nods to the wander line above but also “All that is gold does not glitter”–from The Fellowship of the Ring. From Tolkien I also followed the spirit of journeys to mountains and rivers. The beauty of leaving nature as is, as much as possible. The art of giving to your community and fighting together against the bad guys. Thank goodness for early literary loves that expand throughout a lifetime, so that magic and awe never go away after childhood. This is really important to me. Even now, reminiscing on J.R.R.’s work, I feel as if I’m under some sort of spell.

For all his major works, look no further than to Goodreads, and see the newest work (August 2018), The Fall of Gondolin, below.

In the tale of The Fall of Gondolin are two of the greatest powers in the world. There is Morgoth of the uttermost evil, unseen in this story but ruling over a vast military power from his fortress of Angband. Deeply opposed to Morgoth is Ulmo, second in might only to Manwë, chief of the Valar: he is called the Lord of Waters, of all seas, lakes, and rivers under the sky. But he works in secret in Middle-earth to support the Noldor, the kindred of the Elves among whom were numbered Húrin and Túrin Turambar…Following his presentation of Beren and Lúthien Christopher Tolkien has used the same ‘history in sequence’ mode in the writing of this edition of The Fall of Gondolin. In the words of J.R.R. Tolkien, it was ‘the first real story of this imaginary world’ and, together with Beren and Lúthien and The Children of Húrin, he regarded it as one of the three ‘Great Tales’ of the Elder Days.

Goodreads Reviews

4.1 rating based on 18,266 ratings (all editions)

ISBN-10: 1328613046

ISBN-13: 9781328613042

Goodreads: 39798828

Author(s): Publisher: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Published: //

Pad Gondolina posljednja je Tolkienova knjiga o Međuzemlju. Između dva sukobljena moćna boga – zlog Morgotha, koji vlada nad vojnom silom u tvrđavi Angbandu, i vladara mora Ulma – nalazi se divni grad Gondolin. Sagradili su ga Noldori, vilenjaci koji su nekad živjeli u božanskom Valinoru, ali su se pobunili i pobjegli u Međuzemlje. Morgoth mrzi Gondolin i njegova vladara Turgona, ali uzalud traži taj skriveni grad. Za to vrijeme bogovi u Valinoru ne žele se miješati usprkos Ulmovu nagovoru.

Prolaze stoljeća. Za ostvarenje svojih nauma Ulmo bira Túrinova rođaka Tuora i u jednom od najveličanstvenijih trenutaka u povijesti Međuzemlja Tuor gleda kako se morski bog diže iz olujna oceana. Tuor pođe u Gondolin, postane glasovit i oženi se Turgonovom kćeri Idril. Ulmo već zna da će njihov sin Eärendel imati ključnu ulogu u budućnosti.

Međutim, grad je izdan i Morgoth šalje vojsku balroga, zmajeva i orka. Nakon detaljno opisane bitke za Gondolin, iz uništenoga grada bježe Túrin i Idril s malim Eärendelom. Trebali su otputovati u Priču o Eärendelu, koju Tolkien nije napisao, ali iz raznih njegovih izvora ona je rekonstruirana u ovoj knjizi.

Pad Gondolina »možda najživlje prikazuje svijet Međuzemlja od svih Tolkienovih djela, a k tome najdublje izražava njegove filozofske teme« (Kane). Knjiga okuplja građu koja je već objavljivana, ali je uspješno zaokružuje, i podastire dojmljivu priču o Gondolinu s minimalnim uredničkim intervencijama. Od tri »velike priče« Drugoga doba Pad Gondolina je napisan prvi, a objavljen posljednji, nakon Húrinove djece i Berena i Lúthien. Čitatelja vodi natrag sve do početne točke cijelog Tolkienova »legendarija« – priče o Eärendelu.

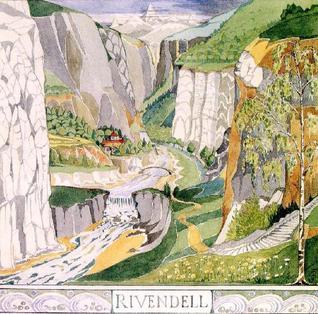

I’ll end this with the thought of Bilbo Baggins singing “I Sit by the Fire and Think” at Rivendell, in The Fellowship of the Ring, the night before the big quest:

I sit beside the fire and think

of all that I have seen

of meadow-flowers and butterflies

in summers that have been;

Of yellow leaves and gossamer

in autumns that there were,

with morning mist and silver sun

and wind upon my hair.

I sit beside the fire and think

of how the world will be

when winter comes without a spring

that I shall ever see.[3]

For still there are so many things

that I have never seen:

in every wood in every spring

there is a different green.

I sit beside the fire and think

of people long ago

and people who will see a world

that I shall never know.

But all the while I sit and think

of times there were before,

I listen for returning feet

and voices at the door.

(from Tolkien Gateway)