Novel by Ohio University emeritus prof asks hard questions.

Plot set in familiar-seeming college town.

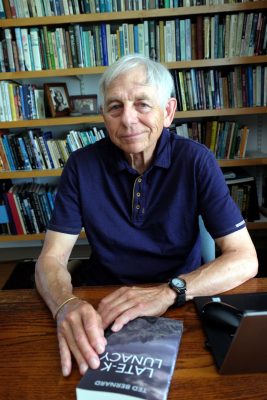

© Jim Phillips, Athens News, Athens, Ohio, USA (June 6, 2018), p. 15

Ted Bernard’s novel Late-K Lunacy opens in a small college town in the foothills of Appalachian Ohio, on the banks of the fictional Shawnee River.

Years ago the university in this town was deeded title to the state’s biggest tract of old-growth forest, in return for a pledge to preserve it. Mineral rights under the forest, however, are owned by an energy company, and now the firm’s owner plans to “frack” the woods for oil and gas. A group of green-minded students launches a campaign to block the drilling, and pressure the administration into switching to renewable energy.

If you’ve been around these parts for 15 or 20 years and this all sounds familiar, it’s no accident. The author makes little effort to disguise the identity of his real-life models; at times he seems almost determined to quash any doubts. His town of Argolis, for example, is famed for its uptown Halloween party, while his Gilligan University of Ohio is nicknamed “Swarthmore on the Shawnee.”

It’s also clear, however, that Late-K Lunacy is after bigger quarry than the gossipy pleasures of a college-town roman a clef. It’s a warning about the fragility of this computerized, fossil-fueled world we humans have built, and how soon it could all begin ripping apart at the seams.

Consider its source, and the warning seems even more dire. Bernard – a professor emeritus of geography and environmental studies from Ohio University’s Voinovich School of Leadership and Public Affairs – has spent years studying the prospects for sustainability. And if he’s worried enough to write a book like this one, maybe we should be worrying, too.

The Late-K of the title refers to a theory called “panarchy,” which explains how complex adaptive systems – ecosystems, economies, societies – can grow so interconnected and short on flexibility that a seemingly tiny shock can send them into a death spin from which recovery is hard or impossible. The concepts of panarchy are presented in excerpts from a book by novel character Katja Nickleby – a scholar who before her death was mentor to one of Late-K Lunacy’s main characters, young, Rumi-quoting professor Stefan Friemanis. The theory has a real-world basis, though, in the work of writers such as Lance H. Gunderson, C. S. Holling and Thomas Homer-Dixon.

Without going into the novel’s depth of technical explanation, the K stage of an adaptive cycle is one in which, to quote from Nickleby’s “Over the Cliff”:

As connectedness tightens, the system becomes more and more rigid, less and less resilient, and increasingly vulnerable to disturbance. To the untrained eye, the system appears to be stable, but this is an illusion. It is only stable within a decreasing range of conditions. Should these conditions shift, everything can quickly collapse. Such is the vulnerability of the Late-K arena.

She adds:

This is arguably the stage where we now find ourselves.

In Bernard’s novel, Stefan’s students, a diverse and articulate bunch, find these ideas mind-blowing and more than a little scary. They start to view the world through a panarchic lens, and to ponder how, for example, climate change might be the trigger to catapult our planet from Late-K into the “omega event” that signals full systemic breakdown, complete with pandemics, chaos, war and starvation. So when obnoxious energy baron Jasper Morse sets his sights on Blackwood Forest, they spring into action to investigate and monkey-wrench his plans.

This kicks off a no-holds-barred thriller plot that includes, but is not limited to, espionage, sabotage, covert surveillance, computer hacking, blackmail, arson, corrupt government officials, shadowy international business combines, secret offshore bank accounts, Cleveland mobsters, sexual bondage games and a fake séance. It might stretch readers’ credulity a bit at some points, but should keep them turning pages. Meanwhile the protest grows into a campus occupation and tensions mount, reaching crescendo in a perfect storm of coinciding crises – including, aptly enough, a monster derecho. To say more might spoil the ending, which is also a beginning.

As a wordsmith Bernard shows a deft hand with phrase and image, especially those drawn from the natural world; when Stefan flirts with a woman, for example, he senses “her coquetry, hovering over my desk like a swallowtail.” The author also has a local’s feel for the nuance of Athens/Argolis culture; he catches nicely the ambience of bar, coffee shop and farmers market, and in a charming grace note, invents an inept but spirited local rock band called “Hot Buttered Blowfish.”

While there’s humor and warmth in this story, as a whole it’s unsettling – not least because its author has penned two books on sustainability, both of whose titles include the word “hope.” Late-K Lunacy is hardly devoid of hope, but it suggests, at least implicitly, that communities working to become islands of sustainability may not be enough to save us; that they’ll be pulled down with the rest when the bigger system, inevitably, crashes. Perhaps, the book hints, now might be the time to think hard, not about how to stave off omega, but how to rebuild a better world in its wake.

Late-K Lunacy is available from various online sites including petrabooks.ca, Amazon and Googlebooks.

Late-K Lunacy. Emeritus professor Ted Bernard (geography and environmental studies at Ohio University) takes a frightening journey into the future.

Complex adaptive systems science informs this novel set in a fictitious university in a small southern Ohio college town; apocalyptic events lead to the 2030s as climate change, the breakdown of systems, and a global pandemic grip the world. The story unfolds with convincing authenticity and concludes with rays of hope as a diminished world builds anew.

Late-K Lunacy, by Ted Bernard. 5.5″ x 8.5″ / 426 pages

Softcover 9781927032831 ($20 USD). Hardcover 9781927032848 ($30 USD)

Petra Books 2018. Distributed by Ingram.

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring opens with a dystopian portrait of a fictitious town dying from pesticides. Mocked by corporate agribusiness, her non-fiction best-seller became the generative force for the modern environmental movement. Late-K Lunacy follows in this tradition with fiction, this time the threat to human and ecological life being a climate change-induced pandemic. It will frighten the complacent and arm climate justice advocates. Ted Bernard has an engaging and imaginative gift for ecology-based fiction.

-H. Patricia Hynes, author of The Recurring Silent Spring (Pergamon)

A devastatingly truthful work of ecology-based fiction and a gripping story of the coming-of-age of a group of post-carbon Millennials. Much more than an ecological dystopia, Late-K Lunacy is a splendid evocation of the world going into – and eventually coming out of – an ecological crisis, as Holling’s ecological cycles are characterized by both collapse and recovery, like a never-ending Möbius strip.

-Fikret Berkes, author of Sacred Ecology (Routledge)