Click here to return to the series

The global novel exists, not as a genre separated from and opposed to other kinds of fiction, but as a perspective that governs the interpretation of experience. In this way, it is faithful to the way the global is actually lived–not through the abolition of place, but as a theme by which place is mediated. Life lived here is experienced in its profound and often unsettling connections with life lived elsewhere, and everywhere. The local gains dignity, and significance, insofar as it can be seen as a part of a worldwide phenomenon.

-Adam Kirsch, The Global Novel: Writing the World in the 21st Century

Thanks to vacation and subsequent long-ish Covid in October, my previously planned research and spotlight for November is delayed until next year. So this month I’m rebooting one of my earliest spotlights from years ago and adding some extra content. Virtually travel with me to Australia and beyond to revisit some of James Bradley’s novels.

Ghost Species

Ghost Species (2020) takes place in the near future in Tasmania. Climate catastrophes by then are rampant, much like they are becoming in our world today. A wealthy man named Davis funds the design of genetically modified plants to combat climate change. Another branch of Davis’s foundation modifies extinct megafauna and also plans to engineer a human-like species from the past. A scientist named Kate Larkin aids in the creation of baby Eve, a Neanderthal child, but Kate questions the ethics of the experiment and she leaves with child, raising her. Davis ensures that they are kept under surveillance, but returning the woman and child to the facility would make him look bad. The novel questions our humanity. Who and what is natural, and what is artificial? Are we becoming extinct?

I’ve often thought of weird fiction when it comes to imagining a haunted world, and many classic stories of the uncanny are figuratively imagined, with tropes like charnel grounds, human species morphed with various aspects of flora or fauna, genuflecting trees, and a great rewilding wherein the idea of human is Other or missing altogether—and is extinct. Ghost Species takes a more literal look at our haunted world and seems more pragmatic in a what-if scenario. Billionaires do often make bad decisions. Combating climate change might have morally challenging tactics, when we could have prevented the worst of its effects rather than scrambling to fix it later. Having followed James’ novels and essays for years, I have found him to be a wildly empathetic and talented writer, compassionate about our natural world.

The Silent Invasion, The Buried Ark, and Clade

I first spoke with James Bradley in September 2017 after reading his novel Clade. We also talked about Silent Invasion, the first book in his young adult trilogy titled Change. He told me:

I first spoke with James Bradley in September 2017 after reading his novel Clade. We also talked about Silent Invasion, the first book in his young adult trilogy titled Change. He told me:

The trilogy is set a decade or so from now in a world altered by the arrival of alien spores, which have begun absorbing Earth’s biology into a kind of hive mind, and although they deliberately play with a series of tropes from classic science fiction – alien invasion, replication, the uncanny – they’re also very much about using those tropes to explore the psychic and environmental disturbance of climate change, by suggesting a situation in which the landscape has become quite literally alien. So while the three books that make up the series are much more explicitly science fictional than Clade they’re also an extension of it in some ways, because they grapple with many of the same questions, albeit in a series of books that have been written with younger readers in mind.

The second in the series, The Buried Ark (May 2018) has also been published. The trilogy begins in 2027, and the human race is dying. Plants, animals, and humans have been infected by spores from space and become part of a vast alien intelligence. When 16-year-old Callie discovers her little sister Gracie has been infected, she flees with Gracie to the Zone to avoid termination by the ruthless officers of Quarantine. What Callie finds in the Zone will alter her irrevocably, and send her on a journey to the stars and beyond. In The Buried Ark, Callie is deep in the Zone—exposed, broken, and alone. Without her little sister Gracie. Without Matt, the boy she loves. But when she stumbles upon a secret—hidden deep within herself—she realizes that she holds the key to defeating the Change. But the Change knows this too, and they will stop at nothing to capture her. Fleeing from the officers of Quarantine, and the pervasive Change, Callie finds refuge in the unlikeliest of places. Only to find that she is in more danger than ever before.

In James’ article “Why I decided to write a novel for teenagers about catastrophic climate change” in The Guardian, he stated:

The Silent Invasion is set in the age of environmental apocalypse, where even the landscape is frightening. But writing about climate change matters–most of all for those who will inherit the world…I also realised I was writing a kind of book I hadn’t written before, one aimed as much at younger readers as at adults. The notion that I might write something for teenagers had been at the back of my mind for a while, partly because having kids of my own had led me back to the books I loved when growing up.

What inspires his writing seems to be the haunting realization that climate change invades our reality and unsettles our cultural and physical norms, like an alien, a common trope in ecological weird fiction. That he builds that into the Change trilogy may help us become more aware of the kinds of large changes that our world is seeing and will see. The trilogy brings to light weird biology and also is full of beauty in the natural world that’s eerie and mysterious. I talked some with James about this, particularly in reference to his novel Clade, a multi-generational story that includes teens and young adults as well. He said:

I think the idea of haunting is a really powerful one. One of the great ironies of contemporary Western culture is that many—if not most—of us exist in a state of constant denial about the human and environmental cost of our lifestyle. That sense of simultaneous awareness and willed ignorance emerges in different ways, but describing our sense that things are not right, that the weather is weird and wrong, that things are out of control as a sort of haunting is a good way of getting at how it feels, and has quite a lot to do with the thread of the apocalyptic and the disordered that runs through so much of contemporary culture. Robert Macfarlane argues something similar in his fantastic essay about the rise of the eerie in contemporary English fiction, but really, it’s everywhere.

So in that sense, I suppose Clade is a kind of ghost story, because it’s a book that’s quite consciously shadowed by a profound grief about what’s happening around us. In places that grief is expressed through the characters and their lives, and through the steady sense of diminution the characters live through, but it’s also addressed more explicitly, through a dialogue with the actual physical effects of climate change.

That’s partly deliberate, but it’s also inescapable, because you can’t write about climate change without writing about loss, whether of species or abundance or simply of possibility. That loss was very much on my mind when I wrote the book, because I have young children, and I’m acutely aware that the world they will live in will be a poorer—and probably less pleasant—world than I’ve known, a world without coral reefs, with less diversity, fewer birds, fewer animals, and probably more conflict and violence. As a parent that makes me terribly sad, but as a human being it makes me incredibly angry, because it’s really a form of theft—our generation and the generation before us have stolen them and the planet’s future.

But while the book is very much about those things, I also wanted it to do a couple of other things. As I’ve already said, I wanted to give people an affective sense of what it might be like to live through the next century or so. But I also wanted to create space for people to think about the possibility of change. Frederic Jameson famously said that it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism, a notion the late Mark Fisher picked up on when he described capitalism as filling every horizon and blotting out all alternatives. But once I started thinking seriously about time, and deep time in particular, I found myself reminded of the degree to which a consideration of both reminds us that the future isn’t set; it’s contingent, which means it can be changed. So, although the book doesn’t set out to offer alternatives, it quite deliberately makes the space for them, both by setting the events of the book against the immensity of geological time, so we’re reminded that our lives, our economy, our politics, are really little more than blips, and by emphasising the way history keeps happening, even after what appears to be the end.

In Strange Horizons, Octavia Cade explores the slow apocalypse and how it can be handled in fiction, opposed to a catastrophe that has a notable start and perhaps end, one that may even be able to be resolved with technology (such as the scientists in Ghost Species want to do). Climate change, like the invasion in The Silent Invasion, is “…so massive, so widespread, that vast amounts of the globe—and of the country—has been abandoned.” The long, slow invasion is spread by invisible spores—much like climate change, a hyperobject so massive and unseeable to the eye as a thing in and of itself. Certainly, its byproducts are measurable and frightening, but when dealing with it, on its own, as either a hyperobject or a topic in literature, I think James’ idea of silent invasion is fitting and helpful to audiences grappling with the global warming.

When talking about climate change in fiction, and how to deal with hyperobjects in storytelling, James said:

Anxiety about the climate and the environment is everywhere in contemporary culture, so that’s not surprising. Just personally I’m not keen on the idea climate fiction is a new genre, or a kind of sub-genre of science fiction. That’s partly because of the heterogeneity you mention and the fact so much of the work deliberately transcends traditional genre categories, as well as the fact describing it that way means we end up thinking about the whole phenomenon in such a literal way, when in fact the anxieties and experiences it explores intrude into so many things in more tangential and metaphorical ways. But it’s also because I think those experiences and anxieties are now so inescapable that it’s more accurate to think of them as a tangible condition, in the same way modernism was, and any work that genuinely seeks to engage with the contemporary world is necessarily shaped by our sense of environmental crisis, and the immense challenges it poses to us not just as writers and artists, but as a society.

As we move forward into the age of the tangible condition of climate crisis, and will continue to engage with this condition in art and literature, I think we’ll have no shortage of creative and unique storytelling for all audiences, young and old. Boundary-less genres and alien subjects appeal to me, for they allow writers and readers to enter into a new world of storytelling that “blows our minds with wild words and worlds” (the motto of this site). The Change trilogy does just this while also exposing its readers to the wilderness of Australia and the off-the-beaten-track world that seems forgotten in our modern world of screens and walls. And what better way to give teens and young adults a slice of hope than with a natural leader like Callie doing what it takes not just to survive but to care for those she loves? So, for younger readers who like mystery and want to explore climate change within fiction, discover more about our beautiful and often eerie natural world, get to know a natural heroine like Callie, and get wrapped up in a great trilogy, I would recommend The Change.

For readers wanting to learn more about weird ecology in fiction, see my series at SFFWorld.com: Part I, II, and III.

About the Author

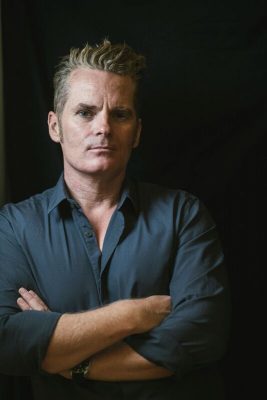

James Bradley is an Australian novelist and critic. His books include the novels Wrack, The Deep Field , The Resurrectionist, Clade, Ghost Species, a poetry book Paper Nautilus, and The Penguin Book of the Ocean, as well as The Change Trilogy for young adults, the first two books of which, The Silent Invasion and The Buried Ark, are published by Pan Macmillan Australia. James has written for numerous Australian and international publications, including The Times Literary Supplement, The Guardian, The Washington Post, The Australian Literary Review, Australian Book Review, The Monthly, Locus, The New York Review of Science Fiction, Griffith Review, Meanjin, Heat, The Weekend Australian, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age. In 2012 he was awarded the Pascall Prize for Criticism. James is currently working on a nonfiction book.

James Bradley is an Australian novelist and critic. His books include the novels Wrack, The Deep Field , The Resurrectionist, Clade, Ghost Species, a poetry book Paper Nautilus, and The Penguin Book of the Ocean, as well as The Change Trilogy for young adults, the first two books of which, The Silent Invasion and The Buried Ark, are published by Pan Macmillan Australia. James has written for numerous Australian and international publications, including The Times Literary Supplement, The Guardian, The Washington Post, The Australian Literary Review, Australian Book Review, The Monthly, Locus, The New York Review of Science Fiction, Griffith Review, Meanjin, Heat, The Weekend Australian, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age. In 2012 he was awarded the Pascall Prize for Criticism. James is currently working on a nonfiction book.

James lives in Sydney, Australia, with his partner, the novelist Mardi McConnochie, and his daughters, Annabelle and Lila. If you’d like to know more about the author, this interview in the Sydney Review of Books isn’t a bad place to begin. Also of note is a talk that James had with Iain McCalman, professor and co-director of the Sydney Environment Institute, covering “Storytelling in the Anthropocene.”