Part XIII. Women Working in Nature and the Arts

An Officer of the Order of Canada, Lorna Crozier has been acknowledged for her contributions to Canadian literature, her teaching and her mentoring with five honourary doctorates, most recently from McGill and Simon Fraser Universities. Her books have received numerous national awards, including the Governor-General’s Award for Poetry. The Globe and Mail declared The Book of Marvels: A Compendium of Everyday Things one of its Top 100 Books of the Year, and Amazon chose her memoir as one of the 100 books you should read in your lifetime. A Professor Emerita at the University of Victoria, she has performed for Queen Elizabeth II and has read her poetry, which has been translated into several languages, on every continent except Antarctica. Her latest books are The Wrong Cat and The Wild in You, a collaboration with photographer Ian McAllister. She lives on Vancouver Island with writer Patrick Lane and two cats who love to garden.

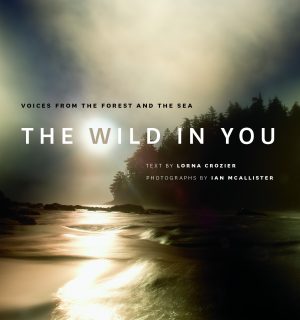

I was very happy to get in touch with Lorna, whose book The Wild in You I read (by solar lamp) on Earth Hour this year. Having been to various areas within the Great Bear Rainforest, and living just south of that area, I have often been by mesmerized by the great trees, the old-growth forest floors, the lichen and birds and salmon and other wildlife abundant in the area. I wish to thank Lorna for her time and for revealing to Eco-fiction.com her thoughts about the forest and The Wild in You.

Mary: Your book of poetry reminds us that we are wild within, and you remark in the introduction that as you grow older, you grow lonelier. Part of it is that as we age we begin watching friends and family pass away. But your loneliness is also born of saying good bye to the wilderness left on the Earth. “It’s the loneliness that comes from wiping out of songbirds, salmon runs, and old-growth forests. It comes from trophy bear hunting…” and you go on to name our losses. I understand this feeling, but not all do. How does one truly find their own connection with nature in a world of congestion, buzzing around, concrete, traffic jams? I think your words, and Ian McAllister’s photography, can help with that. How important is writing about nature to you? Have you taught nature writing before?

Lorna: Though The Wild in You is the only book I’ve published that focuses entirely on the natural world, I’ve written about it all of my life. In my 2002 collection, Apocrypha of Light, I dove into Genesis and tried to tell those old stories through a feminist and pagan perspective. What if God is not the grandfatherly, white-haired man that has become the standard Biblical image? What if God doesn’t resemble a human being at all but instead lives in the form of a horse or a cat? What if the force that brought the world into being is nothing more or less than snow? In one poem, it’s God’s wife that does the creating of the animals because he’s been distracted by making light, not only on the first day but also on the second, the third, the fourth. In the opening poem in The Wild in You I imagine that the progenitor of the world is a female grizzly. Given that, what would the days of creation look like? Well, on the first day, she’d definitely create salmon, five kinds. I’ve taken on these religious stories and tried to reshape them because I want to shatter the idea that humans, particularly men, are at the top of the hierarchy and that all other creatures are there only to serve. A snake is holy, a gopher is holy, a wolf is holy, a crow is holy, a woman is holy. Ian’s photographs make me feel the sacredness of other living things, including trees. I want my words to insist on that too. As we destroy one species after another we become smaller, lesser, more alone. I bet there’s now a psychological term for that. We’ve been de-natured out of ourselves, we’ve been severed from ancient connections that our senses once knew—the smell of a predator in the air, the feeling of wind created by wings, the tremble of the earth felt in our legs and feet when a huge grazing herd passed near. In order to be fully what we are we must allow other creatures room to thrive. Even though our lives are busy, even though most of us live in cities. All my writing, in one way or another, is nature writing. It’s a strange human thing that we think we are outside of it, that we are not an integral part of nature. We are its most terrible predator, its most noxious species. Perhaps if we consider ourselves separate, if we forget our kinship with birds and trees and otters and cougars, it allows us to destroy.

Mary: I agree that when we feel separate, we might act against. When you went about the writing process for this book, how did you form your poetry? For instance, the first poem “Water” is next to Ian’s photograph of deep red and translucent pink starfish cuddling a rock while kelp and green water bubbles above to a bright hole of a sky beyond the surface of the sea. Did you look at a photo and build a poem around it, or was it the other way around, with Ian matching photos to your words?

Lorna: When Ian and I first discussed the possibility of this book, we were both wary. I can’t write poems to order; nor do his photographs work that way. But because we liked each other, we trusted each other, he suggested that he’d send me some photographs and we’d see what happened. No promises. I was thrilled by what arrived. Some of what I wrote grew out of the pictures he sent me; other poems came from the time I spent in the rainforest in the drenching rain seeing my first grizzly calmly eating berries just across the estuary from where I stood. How could I not be inspired by placing my feet in the path the bears had followed for hundreds of years? Or from looking down the gullet of a humpback whale as she bubble-netted, her calf at her side? I also couldn’t stop thinking of what it meant to be the one behind the camera, to have spent so many hours among the animals that they accepted you as kin. Many of the poems came out of my experience and my contemplations, and Ian found photographs for them. It was a true partnership.

Mary: And it worked so very well! These poems are inspired by the temperate rainforest in British Columbia, a portion of which is called the Great Bear Rainforest, a place of secrets, myths, and butting heads with industry (oil, LnG, logging, mining, hydro, etc.). I heard Ian McAllister give a presentation years ago in Burnaby. He and Andrew Nikiforuk talked about the oil sands, the tar-like oil that is so thick it needs to be mined and diluted and injected and piped. One of the proposed pipelines has been the Northern Gateway, but it has so much opposition, not just from local peoples but from environmentalists and even celebrities world-wide. Such expansion of marginal “dirty oil,” as Nikiforuk called it, would contribute substantially–ground to wheel–to climate change, so it is a global problem. Not only that, but the Northern Gateway pipes would cross the rainforest and foul the coast with ships and potential spills and leaks (your poem about it calls this potential a song we don’t want to hear). Yet, when you come here to the rainforest–as I have journeyed to myself–there is a kind of great silence there. It awes you. How could anyone be shooting bears or wolves, or piping oil through, or building ocean net pens for invasive salmon to be farmed, or fishing all the wild salmon away? What were your thoughts when you visited and saw it first-hand?

Lorna: Perhaps one of the greatest gifts of trees, particularly old trees draped with moss, is the silence they give to those who move quietly among them. That silence comes from the ocean, too, when humans are not roaring across the waters. One of the things that governments aren’t addressing is the destruction of that silence if tankers are allowed to use the rain coast as highways for the shipment of oil. Even if there isn’t a spill, acoustically tankers will destroy this pristine place. Fish aren’t deaf, whales need quiet to hear each other’s songs. Can this place not be a sanctuary of quiet for the creatures that call it home? Somehow Ian’s photographs capture the silence of this place he calls home. Among the images that his camera finds you sense a bodiless lack of noise. To try to find words to create a poem seems almost a sacrilege. Yet I think of what the writer Gary Snyder insisted: “some things can only be said in poetry.” If you’re a poet, you must say them. That’s what I’m after. What can my small voice do to protect this vulnerable unique wilderness? When I was there, I thought I’d lay my old body down in front of any tanker that came near. My words, too. I lay them down.

Mary: Thank you for that. Your poems in this book reflect all that is wild in the rainforest–wolves, bears, salmon, sea lions, birds, jellyfish, water, rain, seasons, whales. And you include the person in the forest as wild too–at least the person who is not there to destroy but protect. The wild is mirrored in the photographer’s eyes; it is reflected in the hare’s eyes staring back at the photographer. Alluding to Thoreau you say, “A walk changes the walker…A rainforest changes the man, it changes the woman.” At that point in my reading, I teared up. I run, a lot. My preference for where to run is in a pocket of urban rainforest near where I live, which is often quiet and a place to be changed. So I kept reading that poem, recognizing how I have changed just from running trails. Have you heard from others that get what you’re saying? Or who are inspired to want to walk in the rainforest? To feel the wild within?

Lorna: A First Nations’ Elder once said that we get wisdom from places. In order to receive that, we must know all its seasons. We must pay attention to its vegetation, its sounds, the tenor and characteristics of the light. We must keep our eyes and heart open for the other creatures who live there. We must remember that the water we drink comes not just from reservoirs designed by city planners, but from the streams, aquifers, and rain clouds within a certain radius of where we turn on the taps. When we drink, we are drinking the particulars of a place. If we lived on farms as my parents did, we’d know those particulars in our muscles as we pumped water from a well into a bucket and carried it to the house. One well, even on the same property, tasted different from another. What we drink—the salts and other minerals from the earth— keeps us alive, it revives us. It feeds our blood and bones.

A clump of dirt from the floor of the rainforest is sui generis. So is one from my back yard. The soil that grows my vegetables is different from my neighbour’s. One of my friends claims she knows the taste of potatoes grown on her childhood farm. It’s distinguishable from any other. Somehow we’ve lost this sensibility, this awareness. If we’re not open to weather, to geology, to foliage, we’ve shut ourselves up in suits of steel. Think of what we miss. The land speaks to us if we’d only listen. Trees speak to us. The wind speaks to us. I hope these poems and Ian’s photos light up the desire to see and listen to the richness of the rainforest and, by extension, the richness of the desert, the prairies, the tundra, the boulevards and parks and trails that offer, in their own way, sips of wisdom.

If we’re lucky enough to get into the wilderness, our bodies and our spirits crackle with life. Our legs on a trail feel stronger. They become animal again. Our sense of smell is honed. Raven speaks to us in one of the 200 dialects ornithologists have been able to measure. When a grizzly inhales my scent, I live for a moment inside his body, inside his mind. How can I not be changed? To get inside myself in a deep and meaningful way, where I might, if I’m lucky, find words to say what can’t be said, I have to get outside. I have to be larger than myself. Rain-drenched, I have to breathe in the wolf, the grizzly, breathe in the wild beauty of the world. And I have to figure out what to do to protect it—to stop all those human things that are causing such harm. The most optimistic part of me hopes the poems are one small way to do that.

Mary: I believe your poems are a strong way to counteract our destructive selves and get more in tune with our reconstructive possibilities as we become in the wild. In “Winter,” you point out that winter knows before we do that it is coming. It’s alive. It’s a conscious entity. I feel that nature knows us better than we know ourselves. Your book is both a plaintive tale of caution, and a wondrous one of reflection of nature, so thank you very much for letting readers know that we can connect strongly to the wild and not feel separate from it. That we can be it–with a lot of respect and honor. Circulating back to saying good bye to wilderness, do you have any hope that art and literature can help change people’s minds; that we can be the dripping water that hollows out stone, not through force but through persistence [Ovid]? Do you see the world changing for the better any time soon in the off chance maybe we can start saying hello instead?

Lorna: I once heard the poet Ted Kooser say that every poem, in one way or another says, “We loved the earth but we could not stay.” He couldn’t remember the source of that quotation, but it speaks so clearly to me. I hope that’s where my words take a reader. The Earth is our beloved. The sparrows, the herring that silver the ocean in the spring, the mother cedars, the crabs that scuttle sideways to go forward. My poems pay attention to them now because my time here is short. I must be fully awake because my little life is “rounded with a sleep.” I hope the poems help open another’s eyes, too, so the light of the wild can enter.

Mary: Lorna, thank you so much, both to you and Ian, for this lovely book of photographs, poetry, and inspiration. Even as one whose eyes I would like to think are open, it is possible to open wider after reading The Wild in You.

The poem you quite is from Loren Eiseley. He was a poet and well-regarded anthropologist from the University of Pennsylvania where I went to college. He died in 1977. The quote is also on his tombstone at West Laurel Hill Cemetery. -Chris Robbins