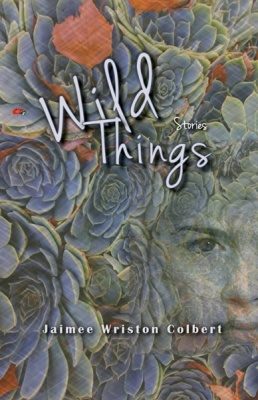

Jaimee Wriston Colbert is the author of Wild Things, a new linked story collection from BkMk Press, 2016; Shark Girls, from Livingston Press in November, 2009; a linked stories collection, Dream Lives of Butterflies, which won the gold medal in the 2008 Independent Publisher Awards; a novel in stories, Climbing the God Tree, winner of the Willa Cather Fiction Prize; and the story collection Sex, Salvation, and the Automobile, winner of the Zephyr Publishing Prize.Her stories have appeared in numerous journals, including The Gettysburg Review, TriQuarterly, Prairie Schooner, Tampa Review, Connecticut Review and New Letters, broadcast on “Selected Shorts,” archived in “New Letters on the Air,” and anthologized. Three recent stories won the Jane’s Stories National Short Story Award; the Isotope Editors’ Fiction Prize; and the Ian MacMillan Fiction Prize.

Mary: Thanks so much, Jaimee, for taking the time to talk about your newest book, Wild Things, a collection of rural noir stories. These interconnected stories are about the wild, the endangered, the extinct. The novel comes out today (October 15, 2016), so I’m very happy about the timeliness of this chat.

I liked reviewer Pam Houston’s take, who said, “Jaimee Wriston Colbert has written a book of deeply affecting elegies to the scattered remnants of wilderness, the some few wild things we still live among: blackbird, brown trout, reef shark, teenage girl.” I thought this statement was clever and right-on. What made you so inspired to create such an intricate web of stories about our world?

Jaimee: The decade after 9/11, 2001 seemed such a perilous, disturbing time, leading up to the 2008 recession and its after-effects, with increasing exposure to the looming disasters of climate change, and pernicious income inequality–great wealth for a few and so many others suffering. I live in a rural area not unlike the one I describe in Wild Things, and it was heartbreaking to watch the decline due to jobs downsized, companies closing, manufacturing disappearing. Along with all of this, the frequent reports about all the amazing and beloved species that are becoming endangered due to human greed—elephants, whales, rhinos, honeybees, the list would take up too many pages! I think many of us felt helpless, bombarded, even threatened, and not sure what to do about any of it. On top of these universals I also suffered some personal losses, and after a few years of deep depression over all of the above, I emerged the way a writer must—with stories to create. Not that I set out deliberately to write about any of these things, but as the stories unfolded, it was clear that the environment, both universal and personal, was greatly affecting what I wrote, which is a good thing. I believe writers and artists should indeed be chroniclers of our times.

Mary: I am sorry that you also had to go through personal losses, and I know writing can be one way to deal with it all. Your writing style is humorous, raw, and very real. This kind of storytelling can help the reader cope with horrors around us too, I think. And I couldn’t put the book down once I picked it up. I was so drawn to your stories because they don’t ignore our real habitat, and they remark on how humans deal with the conflicted natural world that is threatened now by climate change and other environmental issues. We sure are complicated animals, aren’t we?

The characters in your stories are related to characters in other short stories in the collection. The reader may not notice right away, but then it is evident finally. And the characters are downtrodden, yet there are hints of hope and reminders of the strength of humans, who, no matter how hurting, still dream and look up. How do we keep finding hope in our world–especially when we live such desperate lives? How do we live within the elegy?

Jaimee: What a beautiful and intriguing question: how do we live within the elegy! We are indeed complicated animals, and perhaps an answer lies within what you pointed out, that the characters in Wild Things are connected to one another, and to each other’s stories, however obliquely. Though I am personally at my happiest when I am alone in nature, I don’t kid myself that “saving” this nature is anything I’d have a shot at alone; our world’s sustenance depends on communities (and countries!) of hopefully like-minded people who work together to find solutions. So too in Wild Things, there is a community—in fact originally I called the book a “story community” instead of a collection. The area is mostly poor, and the inhabitants (my characters) are very much affected by the loss of manufacturing jobs, on top of the great recession in 2008, but they push on and find hope in each other. Janis picking wildflowers for a depressed Ruth, curled up on their bed. Even Jones, who in his own misguided innocence, believes he is rescuing Loulie from greater harm when he abducts her. And then there is Loulie’s mother Annalee, who never gives up hope that her daughter will be found. The girl’s hoodie that appears in various stories after it’s discovered in the woods, was meant to represent how in a community, when something happens to one person, it becomes a part of everyone’s story, in the ways people in our real-life communities are also connected by events, both celebratory and destructive. The flood in “Aftermath,” an environmental act that devastates the community, shows people helping each other, working at the shelter, or even TJ and his pals playing poker to contribute to United Way. This flood was based on an actual flood that happened in the area I live in, and it was heartening to see how disparate people in the community came together for each other.

Mary: This community-minded spirit to do right in the world seems to be a great way to explore the several recurring tropes, or perhaps themes, in Wild Things: extinction, wildness, meth users, glaciers disappearing. How do you think connecting with nature is important in literature?

Jaimee: I think I’ve always been a “nature” writer, in that place, whether a particular country, region, town, etc. for me is as significant as character. In much of my work, place is character, and characters are developed and made complex within their relationship to where and how they live. My previous novel, Shark Girls, was mostly set in Hawai’i (where I’m originally from), and it depicted island life, how deeply island culture is affected by the ocean surrounding it. A young girl loses her leg in a shark attack and changes in profound, mysterious ways, which delves into both Hawaiian mythology and the Catholic concept of the “victim soul.” I did a huge amount of research into shark biology, and the ocean eco-system sharks are a part of, in the same way I researched and wrote about the disappearing prairies in my book Dream Lives of Butterflies, set in St. Louis. Because my characters are a part of these environments, their lives and consciousness are affected in much the same ways we humans are affected by where we live—both in the immediate, our towns, cities, and on the larger-scale, our planet. I can’t imagine writing a book that doesn’t connect with nature, anymore than we can divorce our human fates from nature. And given how endangered “nature” is becoming on our planet—we have recently passed the carbon tipping point, I see it as an imperative to feature some of these themes, at least in my own fiction. As for meth, well, alas, in the rural areas of the U.S. this has become big business. It destroys lives, families, and going back to one of your previous questions for a moment: it is an act of hope that Teeny in “Suicide Birds” is able to get herself off it and even rescue, at least for the moment, her friend Andrea. Women helping women while her husband builds his “robot wife” in their garage!

Mary: This is what I love: main characters rising above themselves no matter how hard–redeeming themselves.

Having traveled to Oahu a few times and staying in run-down cottages by the North Shore oceanside–constantly mesmerized by that surf and sea, and spending hours and hours in the water, letting the waves take me, and even talking with local fishermen–I now want to read Shark Girls!

If you ever read Arcadian or pastoral type literature, or just the old precursors of contemporary eco-novels, it seems that culture and the literature surrounding it used to be greatly nurtured, inspired, and defined by the physical environment. Now it seems to be different; life and our stories/interests (not mine, but many) seem to be defined by how much money can be made on resources from nature rather than the simple pleasures of being not only surrounded by wild things but immersed in their presence. So I get where you are coming from. Have you been inspired by other authors who write what has been termed “eco-fiction,” a branch of literature that connects humanity with the natural world around us? And who might those authors be?

Jaimee: Non-fiction “nature” writers originally inspired me: Wendell Berry, Annie Dillard, and Rachel Carson. I have a quote from Wendell Berry’s “The Peace of Wild Things,” one of the most moving poems ever written (in my opinion!) at the beginning of my own Wild Things. I poured over Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, reveling in the beauty of her prose, the complexity of thought mirroring the wonders in nature, and Silent Spring, oh my, it left me speechless—and eternally grateful for what Carson exposed about DDT. Whenever I see pelicans I think of her. As for eco-fiction, Ship Fever by Andrea Barrett was a favorite—how she was able to weave history and science into a collection of stories was fascinating. I’m also a huge Margaret Atwood and Barbara Kingsolver fan. I was absolutely blown away by Flight Behavior; it brought me to my knees in places. I have loved Monarch butterflies since I was a little girl (in fact they appear in almost all my books, including Wild Things), and that they are becoming threatened, along with honeybees, by our pesticides, logging, our human greed and careless behaviors makes me want to weep.

Mary: It’s funny that you mentioned Barbara Kingsolver. I will bring that up again in a moment.

Along with these ideas, connecting to the wild in stories is a morally inspirational goal, but the stories themselves have to be worthy to begin with for readers to approve–which yours are. How does one write this fiction without being preachy, then?

Jaimee: Well, I did say I felt an “imperative” to expose these things in my fiction, and after I wrote that I thought, gee, I hope that doesn’t sound didactic! Because of course story is about stories—people read fiction to be immersed in story—John Gardner’s the “vivid and continuous dream,” and no one likes to be lectured. I am first and foremost a storywriter, meaning it’s all about character, and trouble, and how my characters deal with the trouble they are dealt. In Wild Things they have their personal struggles, and many of these struggles are made more complex, even poignant, by parallels of the environmental destruction going on around them. Sadie in “We Are All In Pieces” is grappling with human loss: the disappearance of her heroin-addicted brother; her mother forcing her to have an abortion she isn’t sure she wants—while at the same time she is reading “nature books” and learning facts about the rapidly escalating species extinctions from our world. Nora in “Erosion” is coming to terms with her infertility, what was once known as barrenness, while around her the rising ocean is literally swallowing the land, houses, wildlife forced to scrounge for diminishing food sources.

Mary: Wild Things isn’t didactic at all, which is a huge advantage for the savvy reader. Great authors can do that, which brings me back to Kingsolver, who wrote Flight Behavior, one of the greatest climate change novels ever–which tells the global warming story in a heartwarming way. The first thing I thought when I began reading Wild Things is that your writing reminded me of Barbara Kingsolver’s because of the kind of prose that makes the reader laugh and cry and be able to relate most intimately to characters—and the ties to rural America, too. There’s no superficial qualities in your characters. In this way, the stories alone captured my heart (so thank you), but I had to admit to grinning largely when you interspersed scenes with ideas of birds and freedom, the wild in and out.

Jaimee: Oh, wow, yes, I am a huge lover of birds! And thanks for the Kingsolver comparison; I’m honored! When Wild Things was going through the revision process with my press, BkMk, sending it out to readers for review, one of them said: there are birds in every story! As in, how can this be? Janis speaks for me in “The Man Who Jumped,” when she reflects on what kind of world we would have, if we didn’t wake up to bird song! They are absolutely a symbol of freedom for me, but also its opposite, threat, wings clipped, song stopped. The numbers of birds that have gone extinct in our world is chilling. In Hawai’i alone, the decimation of the native honeycreepers is heartbreaking. I recently learned Hawai’i is being called the “extinction capital of the world!” So the bird that appears in the “Wild Things – Migrants” story, that Jones speculates looks like the critically endangered Hawaiian Palila, or wonders if it’s a new species, this is meant as a symbol of hope. The bird appears again in “Finding the Body,” and in the epilogue, “The Hoodie’s Tale.” Of course the Palila, an endemic Hawaiian honeycreeper, can’t survive anywhere other than on the slopes of Mauna Kea, where there are the Mamane trees it needs (and drought, fire, pigs, etc. are destroying these trees!), but nonetheless a brilliant little bird that looks like a Palila appears in these stories: is it a new species? Magic? Jones, who feels a calling to both live amongst and rescue nature, takes it on.

Mary: Tales of extinction are really sobering, for sure. It’s like one of those realities that’s easy to try not to think about because it is hard to conceptualize. That’s why I think great stories like yours really help the reader to come to a place—like you mentioned earlier—that says, yes, things (flora, fauna, glaciers, etc.) are going away, permanently. It’s not just evolution, either. It’s largely human-impacted. So to be able to live with the concern for all other living things, and, again, to recognize this at a communal level, and do something about it, is key. Any storytelling that can bring us there has succeeded in helping to make the world a better place—helping us to become better people. Redemption in fiction helps us absolve past mistakes, too, I think. Fiction just adds so much to our cultural narrative and has that emotional rope to hang onto.

Also, for readers enjoying this interview, “The Man Who Jumped” is available as a free-to-read sample at our Green Reads site.

Do you have anything else that you are working on at the moment–or other thoughts?

Jaimee: I have completed a new novel, Vanishing Acts, which is set in the Volcano area of the Big Island (Hawai’i), and features an active volcano, the rain forest succumbing to a massive drought, and a big-wave surfer who believes he can surf himself into invisibility (an amalgamation of magical realism and a physics formula!). I’m also very excited about my new novel project. It’s a departure for me, in that it is in part historical, taking place in the 1800s on the Isle of Skye during The Clearances, along with an emigration ship wrecked off the coast of Nova Scotia, paralleled with a present-day story set on the Massachusetts coast, where climate change with beach erosion is threatening several towns. It’s tentatively called Drowning, a title that reflects what happens literally to two characters, along with the sea swallowing the land, due to rising sea levels. It also explores Celtic mythology—which is challenging, integrating all these elements. It will keep me busy for a while!

Mary: It’s funny because my next novel is set in a futuristic Ireland, where something similar is happening (it’s hard to try to imagine the Cliffs of Moher after sea level rise)–though it’s more of a fantasy–an ecological one, maybe a “new weird” type of novel. It also explores some mythology but most of it is from old Norse, and some newer Germanic, mythology. So I am really interested in Drowning (or whatever you decide to call it).

I am putting both of your upcoming books on my to-read list and would love to talk again after the publication of these new novels. Thanks again, Jaimee. I hope we can keep in touch!