Part XV. Women Working in Nature and the Arts

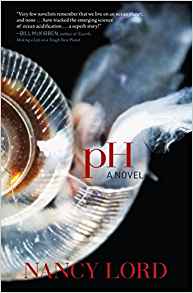

Nancy Lord, who lives in Homer, Alaska, is passionate about place, history, and the natural environment. From her many years of commercial salmon fishing and, later, work as a naturalist and historian on adventure cruise ships, she’s explored in both fiction and nonfiction the myths and realities of life in the north. Among her published books are three collections of short stories and five works of literary nonfiction, including the memoir Fishcamp, the cautionary Beluga Days, and the front-lines story of climate change, Early Warming. She most recently (2016) edited the anthology Made of Salmon: Alaska Stories From The Salmon Project. Her (first!) novel, pH, was recently published by Graphic Arts/Alaska Northwest Books. Nancy was honored as Alaska Writer Laureate for 2008-10, a term during which she traveled throughout the state to promote Alaska writers, writing, and libraries. Nancy is also actively engaged in conservation and community-building causes. She recently completed ten years as a trustee of the Alaska Conservation Foundation and, before that, she chaired Homer’s successful New Library campaign.

Mary: Hi, Nancy, and thanks so much for the chat! You live in Homer, Alaska and have spent years in conservation efforts, particularly via fiction and nonfiction but also in teaching and as a trustee of Alaska Conservation Foundation. What are some of the most memorable experiences in your career?

Nancy: I’ve lived in Homer all my adult life, but I have yet to say that I have a career. I write and teach and have done various other things for work, and I’ve also always been involved in conservation and civic causes. I fished commercially for salmon for many years and am now transitioning to sport fishing. I’ve managed to travel through most of Alaska while researching writing projects and also for a few years as a naturalist and historian on adventure cruise ships. I’ve just returned from two weeks in the Aleutian Islands to do some writing for the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge; it was absolutely amazing to travel by boat to the far end of the Aleutians, to the islands of Kiska and Attu, where World War II battles took place.

Mary: Coming from British Columbia, I see that wild salmon here are dwindling in numbers and I have also volunteered time for raising awareness of them, including a couple paddles on the Fraser River. What’s going on with salmon up where you live, and how do you think warming waters are affecting the fish?

Nancy: Alaska, so far, has managed its salmon well—and hasn’t destroyed the freshwater habitat salmon depend on. Last year I edited an anthology Made of Salmon: Alaska Stories From the Salmon Project, which brought together voices from throughout the state to describe their relationships to salmon—for food, livelihood, and culture. Alaskans very much value salmon and come together to fight for their protection– for example in opposing a large-scale mine in the headwaters of Bristol Bay, home to Alaska’s largest sockeye salmon run. The near-record run there as of late July was 59 million fish. However, in much of the state we’re seeing problems with excessively warm waters and low oxygen in salmon streams, that can affect future runs. The largest threat likely will come with ocean acidification, the result of the ocean absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. This change in chemistry is already affecting marine organisms that build shells, making it harder for them to do that. Tiny pteropods (marine snails) are a significant food for salmon.

Mary: It’s great to hear that Alaskan wild salmon are (so far) faring better than British Columbia’s, but the news about warming waters and acidification is sobering. I’m really impressed with your nonfiction books about life in Alaska, salmon and other fish, whales, the Exxon-Valdez spill, and indigenous life and culture, as well as how global warming affects local communities in Alaska. I marveled at the number of projects you have taken on as well as your commitment to caring about our planet. Could you summarize your five top concerns from these books?

Nancy: It’s true that I’m passionate about the north and especially Alaska, which is what I know best, especially coastal Alaska and environmental issues. Through writing, I’m able to indulge my curiosity about many things and to be an advocate for environmental protection. In my first nonfiction book (Fishcamp) I wrote about the human and natural history around the place where I fished from the beach for many years. Right after that I wrote in Green Alaska about the Harriman Expedition of 1899, contrasting their experiences with my own a hundred years later (and learning that some conservation concerns were more serious then than now.) I wrote Beluga Days when I noticed that the whales in my area were disappearing and set out to find out why. Early Warming captures my efforts to add something to the discussion of climate change, by looking at how northerners are coping and adapting. And the book I edited, Made of Salmon, celebrates relationships between Alaskans and salmon and speaks to the need to safeguard salmon and their habitat.

Mary: It seems your work is vast and very much needed. What are some of your most exciting experiences being outdoors in your great state?

Nancy: I like hiking and kayaking, but my ambition pales compared to other Alaskans I admire. For so many years I spent my summers fishing from a skiff and got to know quite intimately a certain section of beach and the surrounding area. It’s a satisfying way to live. Certainly my most exciting experience was my first Alaska one—at the age of nineteen, spending five weeks hiking, climbing, and rafting in Alaska’s Brooks Range. That was probably the most formative experience of my life, sealing my commitment to living in Alaska and caring for its wild places. I’ve been fortunate since then to visit many other remote parts of Alaska, including Bering Sea and Aleutian islands.

Mary: I did something similar as a teenager–rafting, repelling, and hiking though northern Wisconsin–and yes, I can see how such times cemented my care and advocacy for wild places as well. Your newest work of fiction, the novel pH, involves marine scientists working in Alaska on ocean warming and acidification. Can you tell us something about the novel? How much of your real-life experiences inspired this novel?

Nancy: After writing mainly nonfiction in recent years, I decided to tackle ocean issues in what might be a more interesting and compelling way for readers. pH is a comic novel, with characters in conflict and a plot surrounding institutional corruption. I hope that it has some resonance right now, since it addresses ways of knowing, the manipulation of facts, and ethical choices. The science behind it is all real—the oceans are being affected by warming and acidification. The first section takes place on an oceanographic cruise; I spent a week on one in 2010, which provided the basis for what I describe as work on the ship. It’s hard to pick out, otherwise, what personal experience fed into my imagined world and the lives of my characters.

Mary: Who were your favorite authors growing up, and can you share how their writers particularly affected you?

Nancy: Growing up, I was drawn to stories that took me far from my own home in New Hampshire and encouraged a sense of adventure. The Laura Ingalls Wilder books, Heidi, Peter Pan. I’ve written about the influence of Peter Pan and Siddhartha on me, in two essays in my book Rock Water Wild. Later, when I was becoming a writer, I admired southern writers like Flannery O’Connor and Eudora Welty and essayists like E. B. White and Edward Hoagland. Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek found me at a propitious time and influenced how I paid attention to the world.

Mary: Related to the two questions above, how can environmental literature appeal to readers these days, especially with the glut of global narratives coming at us in every direction–many of them having valid appeals for us to be concerned about so many issues?

Nancy: I think that environmental fiction can have great appeal these days because it can tell compelling stories without being heavy-handed with message. Readers are suffering from “bad news syndrome” right now—inclined to turn away from reading (or hearing) about every new disaster and every thing that we’d doing to damage the Earth and its creatures. Fictions that can tell humorous or inspiring stories seem much more palatable—and can still inform readers about serious issues. Some novels in this line that I admire are Ian McEwan’s Solar, Ann Pancake’s Strange As This Weather Has Been, Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior, and T. C. Boyle’s When the Killing’s Done. Of course, there’s still room for every kind of environmental literature, including reporting; I just think that fiction is having its day.

Mary: I think you’re spot-on with this thinking, that we need to move from the hopeless “bad news syndrome” to understanding what’s happening and the idea that we can do something about it–that we get inspired rather than paralyzed with fear. Thanks so very much, Nancy, and the best of luck with pH!

The featured image is credited to photographer Stacy Studebaker.