Guest interview: Sheryl Johnston (from All Things Literary) chats with Melissa Fraterrigo, author of the new novel Glory Days.

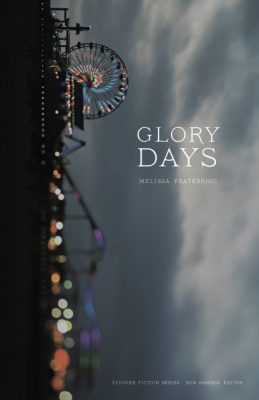

Glory Days by Melissa Fraterrigo Pub Date: September 1, 2017. UK November 1, 2017 Imprint: Nebraska. 175 pages; 5 1/2 x 8 1/2 inches ISBN-13: 978-1-4962-0132-4; Price $19.95

Melissa Fraterrigo is the author of the novel Glory Days (Sept. 2017, University of Nebraska Press) and the short story collection The Longest Pregnancy (Livingston Press). Her fiction and non-fiction have appeared in more than forty literary journals and anthologies from Shenandoah and The Massachusetts Review to storySouth, Notre Dame Review, and Prairie Schooner. She has been a finalist for awards from Glimmer Train on multiple occasions, twice nominated for Pushcart Awards, and was the winner of the Sam Adams/Zoetrope: All Story Short Fiction Contest. She is founder and executive director of the Lafayette Writers Studio, in Lafayette, IN, where she also teaches classes on the art and craft of writing. To learn more, visit melissafraterrigo.com.

Melissa Fraterrigo is the author of the novel Glory Days (Sept. 2017, University of Nebraska Press) and the short story collection The Longest Pregnancy (Livingston Press). Her fiction and non-fiction have appeared in more than forty literary journals and anthologies from Shenandoah and The Massachusetts Review to storySouth, Notre Dame Review, and Prairie Schooner. She has been a finalist for awards from Glimmer Train on multiple occasions, twice nominated for Pushcart Awards, and was the winner of the Sam Adams/Zoetrope: All Story Short Fiction Contest. She is founder and executive director of the Lafayette Writers Studio, in Lafayette, IN, where she also teaches classes on the art and craft of writing. To learn more, visit melissafraterrigo.com.

The small plains town of Ingleside, Nebraska, is populated by down-on-their-luck ranchers and new money, ghosts and seers, drugs and greed, the haves and the have-nots. Lives ripple through each other to surprising effect, though the connections fluctuate between divisive gulfs and the most intimate closeness. At the center of this novel is the story of Teensy and his daughter, Luann, who face the loss of their land even as they mourn the death of Luann’s mother. On the other end of the spectrum, some townspeople find enormous wealth when developers begin buying up acreages. When Glory Days—an amusement park—is erected, past and present collide, the attachment to the land is fully severed, and the invading culture ushers in even darker times.

In Glory Days Melissa Fraterrigo combines gritty realism with magical elements to paint an arrestingly stark portrait of the painful transitions of twenty-first century, small town America. She interweaves a slate of gripping characters to reveal deeper truths about our times and how the new landscape of one culture can be the ruin of another.

Sheryl: Glory Days is a stunning, intricate novel that explores losses of all kinds–loss of loved ones, relationships, farm animals, land, jobs, while it also presents the devastating effects of climate change and human greed. What was the seed of inspiration for your novel, and what came to you first–the characters or their situation?

Melissa: Glory Days is the result of some dark days. In the winter of 2011, a few months after moving to Indiana, someone very dear to me was diagnosed with cancer. Writing had always been a means for me to make sense of the world and now I was unable to read a paragraph much less write one.

I slept poorly and rather than tossing and turning, got out of bed during the wee hours of the morning to read poetry. I found myself captured by the images these poets were using to describe characters and place. It is during times of change when we feel most alone, and in this time of uncertainty, descriptions of the natural world felt like a comfort. I read a lot of Sharon Olds and Gabrielle Calvocoressi and Diane Gilliam Fisher, and while I didn’t have the constitution at that time to write, I felt like I was learning something new about how certain images held tangible weight that extended beyond the page and could even reflect a character’s emotional state.

So as I was becoming more conscious of details on the page, I was also becoming more aware of Indiana and the place where I now lived. One day the parking lot attendant of our local library told me he’d just come back to town, that he’d been south burying both his mother and sister. I don’t know whether it was the look on his face or something else, but I heard a line: “Gardner hears dogs scrambling up the trees after a squirrel or a neighbor’s cat, he tells himself, eager to be calmed.” This became the first line to “Teensy’s Daughter” and that was it. I was back to writing stories, only now creating a place and accurately portraying its landscape felt as vital to me as the development of characters and their situations.

Sheryl: Some of the chapters in your novel have been published as short stories in various literary journals, and you are also author of the award-winning story collection The Longest Pregnancy. How did you decide to make Glory Days a novel, rather than a short story collection? Which is easier to write?

Sheryl: Some of the chapters in your novel have been published as short stories in various literary journals, and you are also author of the award-winning story collection The Longest Pregnancy. How did you decide to make Glory Days a novel, rather than a short story collection? Which is easier to write?

Melissa: Well, I imagine some readers will say that Glory Days is a story collection, as many chapters were initially published as stand-alone stories. But unlike The Longest Pregnancy, these characters haunted me. The book became a puzzle of sorts in that I needed to figure out not only how they were related but also what those relationships meant to the larger arc of the novel. As mentioned earlier, the first story I wrote was “Teensy’s Daughter,” which is now located towards the end of the book. Once I finished it, I needed to figure out how Gardner finds himself on house arrest and why he’s afraid of Teensy and why the ghost of Luann will not leave him alone.

I was reading a lot of novels-in-stories at that time—Cathy Day’s Circus in Winter, Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, and Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteridge—and I became intrigued in the varying amount of “space” inherent in this form. Some of these novels-in-stories were very closely aligned to the novel, where various elements in the narrative fit together to create a very succinct whole, whereas other translations of the form included more ambiguity, with greater leaps of time and situations. In the latter, I discovered a sort of space where I felt the author acknowledge that some gaps remained in the narrative—and I felt welcome to fill in these gaps. With Glory Days, it became a challenge to connect the pieces between these characters and their somewhat tragic situations, while also leaving some space for readers to bring their own impressions to the book, making it theirs.

Sheryl: In its 5-star review of Glory Days, Foreword critic Paige Van De Winkle wrote: “Each chapter is poignant, with moments that are eerie, playful, haunting, and mournful.” She also comments on your ability to weave magical realism and the supernatural into your writing. Why did you decide to incorporate these elements into this haunting tale about a small ranching town in Nebraska?

Melissa: I really don’t have a simple answer. I wanted to write a novel set in a small hardscrabble town populated by folks living during hard times. The characters in Glory Days find themselves in situations they did not plan for, yet all still yearn for the basics—to work, to be loved, to feel as if they belong. The tragic history of these characters and the invading culture of “progress” creates a stark portrait of a time and place in America, and with the weight of these struggles, magical realism felt like an appropriate response to provide further insight into these characters and the community of Ingleside.

Sheryl: Your novel begins with a quote from award-winning poet and essayist Jane Hirshfield, which seems a fitting introduction for the character struggles that lie ahead. Can you tell us why you chose this particular quote to set the stage for your new book?

Melissa: I love Hirshfield’s poetry, especially “Happiness,” where these first few lines originate. I think that no matter how different we are or how unusual our circumstances, we must always try to find some common ground. We must work harder than ever to see beyond the desperate histories and lives so many endure. To me, animals and their connection to the land can teach us many of the lessons we know but repeatedly forget.

Sheryl: Glory Days could be categorized as Gothic or as rural noir, spiced with magical elements. The names of a few authors came to mind while reading Glory Days–Flannery O’Connor, William Faulkner, Ann Pancake, Cormac McCarthy, Aimee Bender, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Would you say, these or any other writers have inspired or influenced your work?

Melissa: All of them! And I’ll add some more—Stuart O’Nan, Michelle Hoover, Breece D’J Pancake, Bonnie Jo Campbell, Daniel Woodrell and Kent Haruf, and the poets Gabrielle Calvocoressi and Diane Gilliam Fisher, to name a few.

Sheryl: You were born in Indiana, grew up in and lived in the Chicago suburb of Evergreen Park. You also attended universities in Ohio and Iowa, and your work as an editor or teacher transported you to colleges in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Utah, Illinois and Indiana. At any point, did you live on a farm, and if not, how were you able to so accurately portray the challenges of farming and raising cattle in today’s world?

Melissa: My babysitter and her husband raise beef cattle and were kind enough to entertain my fascination with these slow-moving creatures. They welcomed me onto their farm and have patiently answered all my unsophisticated questions. While I didn’t grow up on a farm, I do feel most interested in the towns that reside between pastures. To paraphrase Toni Morrison, you have to write the book you want to read. Glory Days is my attempt to do just that.

Sheryl: You write about Ingleside as if it were another character. What would you say is responsible for your strong sense of place?

Melissa: I started the novel soon after returning to the Midwest after living for a year in Philadelphia. During that time my connection to nature was limited to the postage-stamp sized bits of grass where I would walk my dog. While I’ve spent most of my life in the Midwest, it wasn’t until we moved to Indiana that I felt a certain kinship with the fields of corn and beans. Landscape held a new allure. I don’t know if it was because I’d been without wide-open spaces for some time. I do believe there is mystery and a sense of possibility in the back roads and hard-to-get-to places in “flyover country” and these are places that appeal most to my imagination. Thank you for what you said about Ingleside feeling as if it were another character. I can’t think of a greater compliment!

Sheryl: In Glory Days, there’s a striking correlation between the destruction of nature and human suffering. You’ve captured the struggles of a broken Plains town with little word sketches of a much larger, complicated portrait, for example: “Outside Daddy’s boots broke dirt clots, the little land we had left went on unplowed, just stubs of corn, old mud ruts now dry” or “Dust whorls. We sweat. Vultures spoon the sky.” Comparing how the town was before and how it is now, you write: “Smallmouth bass used to leap into a net extended from Red Arrow Bridge, but now they are pale and scrawny things that barely ribbon the water.” How did you manage to communicate so much information with so few words?

Melissa: John Gardner talks about the importance of creating a fictional dream for readers and says that you can use language to bring readers to another place and time and create a sort of dreamlike state for readers. I wanted to make the town of Ingleside real to readers, especially since I thought that some of these characters are not the most emotionally available. So by writing about this place, using some of the same tools I might use to describe a character, I was able to develop a mood and resonance the characters seemed to rebuke.

Sheryl: You are Founder of the Lafayette Writers’ Studio in Lafayette, IN where you teach classes on the craft of writing. You’ve also taught writing at several universities over the years. How would you say teaching informs your work as a writer and vice versa?

Melissa: I truly love teaching. I know without a doubt I have the best gig in the world. There is nothing better than being in the classroom, talking about literature and really listening to students and how their lives inform their readings and in turn their writing. It is an honor and privilege to teach, especially something as intimate as writing. There is an ongoing debate about teaching and its influence on a writer’s productivity. In my situation, teaching fuels me. No matter how much I am struggling with my own work, the questions my students bring to me compel me to think harder, to read deeper, and remain open to a piece and whatever direction it may take. Many of my current students come to writing from a range of circumstances and experiences. Some of them are retired, others are in high school, while still others are working on low-residency MFA degrees—yet each shares an interest in exploring the craft of writing. I owe my students everything for trusting me with their work.

Sheryl: When did you know you wanted to become a writer, and how did you arrive at this place?

Melissa: I always felt a kinship with words and stories and in many ways, I think I was destined to work with stories in some fashion; only it took me a long time to get to where I am. Despite that, I’ve got to say I have the best job in the world.

I taught high school and junior high English for three years after earning my bachelor’s degree. My first job out of college was teaching high school English in a small town in downstate Illinois where the job prospects were few and many of my students were from families that were struggling both financially and emotionally. I really liked my students and loved talking to them about literature, but during that year my grandmother passed and I did some hard thinking about how I wanted to spend my own days. I hadn’t forgotten the desire to be a writer, only I didn’t know how to be a writer and also pay bills.

Somewhere during that first year I told myself to just start writing—just a little bit. I found the more I wrote, the more I enjoyed it. That summer I took at class at the University of Illinois at Chicago—my first fiction class—and met two other women who were also interested in fiction and poetry. For three years we met on a monthly basis to share work with one another and offer each other feedback. I have no doubt that without their support I would not be where I am today. Writers need other writers, and these two friends provided the support and encouragement I so desperately desired.

I love my parents with all my heart, but they were children of parents who survived the Depression. Working toward a degree that would get you a job, which in turn would pay a solid salary mattered more than doing work that fulfilled. Fortunately I listened to my gut and kept writing, following the thrum of excitement I felt each time I drafted a new story or had an idea for a piece.

I attended Bowling Green State University and met a fantastic cohort of writers and instructors of writing—most of whom I’m in contact with today. This community of writers was essential for building the “literary family” that I craved—folks who were also driven to create worlds from their imaginations. We encouraged each other and continue to do so.

After graduate school I taught at various colleges as a visiting professor—Penn State Altoona, Southern Utah University, Penn State Erie—all the while working on fine-tuning my short story collection. This is probably the hardest part about teaching writing—you spend so much time grading papers, planning for classes, yet you also need to devote consistent time to your own creative projects.

University-level teaching demands publications and I found this pressure daunting. I segued into editing and worked as a senior editor at Saint Xavier University in Chicago. My first book, The Longest Pregnancy, was published in 2006. About one-third of the book was written as part of my graduate thesis at BGSU. As time has gone on and my family situation has changed, I shifted into freelance writing for different universities. However, I still missed teaching and three years ago established the Lafayette Writers’ Studio to combine my love for teaching with my desire to help others tell their stories. I started Glory Days a few years before I opened the studio.

Sheryl: Tell us about your writing day. Do you have any rituals or routines?

Melissa: I work consistently early in the morning before anyone else in my family is awake. I find that the writing I do at this hour has a richness to it that I can’t access at any other point in my day. I also write longhand, so as I sip my coffee in the early morning hours and do my thing on yellow legal pads, I’m waking up with words. Later, when I return to these pieces, I really have no recollection of them, so while I am typing the story, I am in many ways being told a story. Another aspect of my routine is that I try and exercise each day. I have solved the most difficult questions of plot and character while swimming laps and I wholeheartedly encourage my students to do the same and use that time in their heads to problem solve. We write stories using our minds, but those narratives also reside in the body, and there is something in the act of being physical that I believe helps us to focus on the marrow of a story in a way that the brain alone cannot.

Sheryl: What are you working on now?

Melissa: There’s nothing better than the excitement of a new project. I’m working on a YA/MG novel that’s a double narrative with one section in the early 2000s and another section from the year prior. I have a draft of the novel and I’m enjoying it, but I also foresee a fair bit of work in my future. Fortunately, I like this part of the writing process.

Author website: www.melissafraterrigo.com