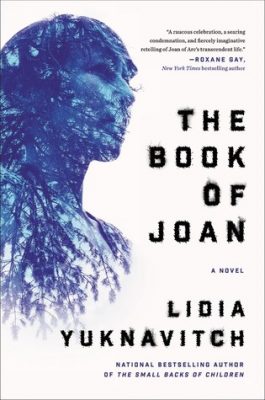

Lidia Yuknavitch is the author of National Bestselling novels The Book of Joan and The Small Backs of Children, winner of the 2016 Oregon Book Award’s Ken Kesey Award for Fiction as well as the Reader’s Choice Award; the novel Dora: A Headcase, and a critical book on war and narrative, Allegories Of Violence (Routledge). Her widely acclaimed memoir The Chronology of Water was a finalist for a PEN Center USA award for creative nonfiction and winner of a PNBA Award and the Oregon Book Award Reader’s Choice. A book based on her recent TED Talk, The Misfit’s Manifesto, is forthcoming. I am thrilled to welcome Lidia!

Lidia Yuknavitch is the author of National Bestselling novels The Book of Joan and The Small Backs of Children, winner of the 2016 Oregon Book Award’s Ken Kesey Award for Fiction as well as the Reader’s Choice Award; the novel Dora: A Headcase, and a critical book on war and narrative, Allegories Of Violence (Routledge). Her widely acclaimed memoir The Chronology of Water was a finalist for a PEN Center USA award for creative nonfiction and winner of a PNBA Award and the Oregon Book Award Reader’s Choice. A book based on her recent TED Talk, The Misfit’s Manifesto, is forthcoming. I am thrilled to welcome Lidia!

Post-apocalyptic fiction too often pays lip service to serious problems like climate change while allowing the reader to walk away unscathed, cocooned in an ironic escapism and convinced that the impending disaster is remote. Not so with Lidia Yuknavitch’s brilliant and incendiary new novel, which speaks to the reader in raw, boldly honest terms. The Book of Joan has the same unflinching quality as earlier works by Josephine Saxton, Doris Lessing, Frank Herbert, Ursula K. Le Guin and J. G. Ballard. Yet it’s also radically new, full of maniacal invention and page-turning momentum.

Mary: I’ve got to start out this chat by saying that if I could choose three writers I would like to hang out with, one would be you. Your TED Talk, “The Beauty of Being a Misfit,” made me, and I’m sure lots of others, see you as a sister, mother, and friend from afar and as a person we could envision sitting in our kitchens over coffee or tea or beer, having everyday conversation. Many of us feel like misfits, and we aren’t perfect, and yet there is power in being flawed and human. Thank you for talking real to us, for being someone we can relate to. Thanks for giving your voice to your stories, which have moved us beyond imagination. Can you explain to our readers how in failure we are still beautiful, one of the ideas in your TED Talk?

Lidia: First let me say THANK YOU for your kind words. Secondly you should know that TED talk nearly killed me…and yet it was STILL worth it, if even one mammal felt less alone or crappy. You know? Failure is the human default. There isn’t a mammal a live who has not experienced failure. Like most things in life, the meaning of failure is what fucks us up–we have so limited what we mean when we say ‘failure’ that it’s just a doom realm. When in reality, failure is omnipresent. It’s the cusp of all imagination. Failure is an idea and emotion and courage catapult, whatever else it is. Failure, from my point of view, is a portal. So the question shifts from, did I fail or succeed, to something like: how is this failure a portal? What is this failure generative of?

Mary: The Book of Joan is inspired in part by Joan of Arc and Christine de Pizane, both historical women who may have been branded misfits in their time but evolved to be legendary heroes. I like how you carry history forward, as a kind of way to connect different times. Going back to your TED talk, where you mentioned that girls need good role models–can you talk a little more about this, and how the novel embodies a woman?

Lidia: Because in America in particular we live at the zenith of high capitalism in what has evolved as an entirely patriarchal culture, a culture of ownership and consumerism and power using the raw material of women, indigenous people and people of color as the raw material from which “progress” has supposedly happened, we are ever having to re-ask the question what it means to be a “woman.” I like to liberate the term and territory of “woman” by dislocating it from history and relocating it in different tenses in order to turn “woman” back into a verb, a mode of being, a category of becoming. While on the literal level YES I agree that girls and boys and non gender binary children need something besides this idiotic capitalistic death culture to look up to, I also thing we need to adjust our lens–why do we look up to celebrities more than hard workers? The reasons are dubious. American individualism and excellence have at their core a dark center–narcissism. Ego. I am interested in exploring subjectivities–past and present–that are not driven by ego, but rather collectivity, fluid understandings between self, other, world, imagination, love.

Mary: How do you envision Joan of Arc/Dirt being the rival of western culture’s hero Jesus? And can you explain the song of God versus the song of Earth?

Lidia: OH MY OCEANS WHAT A GREAT QUESTION! Well for me personally (and likely obsessively), the body of Joan of Arc (I mean the REAL body–the one we burned at the stake) is the only body in Western culture capable of holding its own against the tortured Christ body. One body generated an entire belief system, and by extension, an entire system of male power and authority that relegated woman to other, mother, holder of sacred male seed. So it fascinates me to consider the “what if” of the female suffering body–her body carrying what her culture could not hold, her body the sacrificial site, her body the site of resistance to emergent forms of male power.

As for God songs vs. Earth songs, God songs carry a devotional hymn based on allegiance to a power factiously “higher” than men, and yet utterly in the service of human male systems of power. An Earth song would require us to divert our highest forms of devotion, intimacy, love, sacrifice, and honor toward the planet we pretend is “ours.” An Earth song would require us to listen to dirt and ocean and trees and sky and mountains and rain and rivers as if they were the sacred story of cosmic origin–which by the way, they are. An Earth song carries the chorus of all matter and energy taking form without divine mythologies we constructed to narrativize over our fear about the vastness of life and existence beyond life.

Mary: That’s a beautiful idea. Back to connecting time, The Book of Joan is set in the future, and it feels dystopian but also feels plausible and not too distant from our current reality. Many of us realize the environmental catastrophes happening in the world, and we see traits of Jean de Men in political leaders too. I feel that this novel describes our future and our present and past in many ways. Do you think history mimics itself, and do you think that we have a chance to become heroes like Joan and save ourselves?

Lidia: I think our only option is to begin to recognize that no heroes are going to swoop in and save us, if they ever did, which is in and of itself a fiction. What is called for is a radical revisioning, that would YES include a deep understanding of time and existence as non-linear. Astrophysics and indigenous ancestral mythologies are both screaming their heads off about the fact that the “time as an arrow” or linear time model is pure fiction. The past and the present do not fall neatly onto a linear line. The idea of a “beginning, middle, and end” is a comforting storytelling form, but it is not how reality works. We are fast approaching a new kind of understanding of being that may include multiverses and parallel realities and complete upheavals around what we mean when we say “time” and “existence.” So I think traditional definitions of “history” cannot hold up any longer. It’s not like I’m the first person to think of that–much wiser people than me have been pointing that out for a very long time. History is more multidimensional, multi-voiced, and multi-bodied than we wish it was. Like memory and space, history doesn’t sit still. It’s alive in the present and future tense. Like narrative, it is quantum.

Mary: Yes, I agree and often think of time as a layer of past, present, future, ideas found also in dreams and memories.

In the novel is the comparison between the oil sands of Alberta and our “insatiable desire for refinement”. I dug into this idea–knowing that refinement is really not something misfits need in order to become beautiful (back to an earlier discussion) but also that oil needs refinement in order to work for us (and especially mined oil, like in Alberta, which takes more natural resources to produce than lighter weight oil and, in turn, emits more greenhouse gases from ground to wheel). Can you speak to the idea that refinement might be ruining us–not only in the refinement of oil but of culture, power, fame, wealth, celebrity? How do we unblind ourselves from this supposed progress?

Lidia: OH HOW I LOVE how you are teasing out that idea. YES. The concept and actions of “refinement” operate under the cover story or fiction of “progress” when in fact they are at the heart of our own destruction. What if we radically revisioned our ideas about “reaching for the stars” to mean understanding how we’re made from star junk? What if to “be the best” moved away from winning and owning and conquering and toward some other model–like collaboration and radical empathy and building sustainable existence rather than war and power and fame?

Mary: In The Book of Joan it seems refinement has led to a lot of non-human aspects portrayed in the characters of the story. The rich elite have boarded the CIEL (French for “sky”) satellite and live in it rather than the ecologically devastated Earth below, where people starve, are tortured, and die. They now have no hair, no sexual organs, no diversity in skin, and no children. In this sterile environment of sameness with no chance at continuation as a species, people seem to hyper-identity themselves by using skin grafts, where they burn poetry and art into their skin. Absolutely brilliant. Art and poetry are super-important in culture, aren’t they? Pain is important too, yeah?

Liida: Yes I cop to being seriously influenced by Elaine Scarry’s book The Body in Pain–and in particular how scenes of wounding and trauma in sacred texts worldwide are often generative of belief systems. As for art, I believe in art the way other people believe in god. Making art and being in relationship to art brings us close to life and death and love and pain and a sense of the secular sacred–which is also evident in the night sky if you look up. There above you is our entire existence, which is also inside of a single being or plant or animal.

Mary: The New York Times states about The Book of Joan: “Post-apocalyptic fiction too often pays lip service to serious problems like climate change while allowing the reader to walk away unscathed, cocooned in an ironic escapism and convinced that the impending disaster is remote. Not so with Lidia Yuknavitch’s brilliant and incendiary new novel, which speaks to the reader in raw, boldly honest terms.” I felt this was right-on, that writers may need to speak more honestly in fiction rather than using lip service to explore global warming. Do you think so? And what do you suggest to newer writers wanting to tackle global warming in their novels?

Mary: Yes, I wish more writers put their art-making to use in the real world. But I also understand that some writers give us escape and fantasy, and that’s ok too. Art has room for the entire spectrum of human experiences. What I would suggest to newer writers wanting to tackle global warming or climate change is to consider abandoning the solo hero’s journey happening across a setting which is the background of the story and reconsider the idea that the planet–what we’ve been using as setting–may have a point of view. Maybe the environment has been screaming her story alive since the get-go. Maybe the planet and her corresponding eco-systems and environments never needed humans–but we got a shot at inhabiting this planet–and what we’ve done is tried to discover, conquer, own it in ways that are idiotic and brutal. Maybe newer writers can help us redefine our relationship to the planet, the cosmos, and each other. I hope so. That’s my dare to newer writers. Dislocate all truths. Revision everything.

Mary: You had a horrible childhood, and I wonder if you turned to reading as a way to cope? In a broader sense, how does fiction change people?

Lidia: Reading is a way to open up everything that happens in your life to ten thousand possible meanings rather than the ONE meaning you attach to events and haunt yourself with.

Mary: I read in Variety that Scott Steindorff and Dylan Russell of Stone Village Productions have won a competitive auction for movie rights. How does it feel to get to see your story in a film?

Lidia: HA. I haven’t seen my story in film, except in short amazing artistic translations from fellow artists…but if that ever happened for real, I’d be thrilled to see the NEW story and form that came from the portal of my tiny piece of art. Art generates more art. I’m for that.

Mary: Awesome. Thanks again, Lidia, for taking some time to talk with Eco-fiction.com. I look forward to your future projects!

The feature image of Lidia is by Rachel Kramer Bussel (Flickr), CC BY-SA 4.0