Back to the Indie Corner series

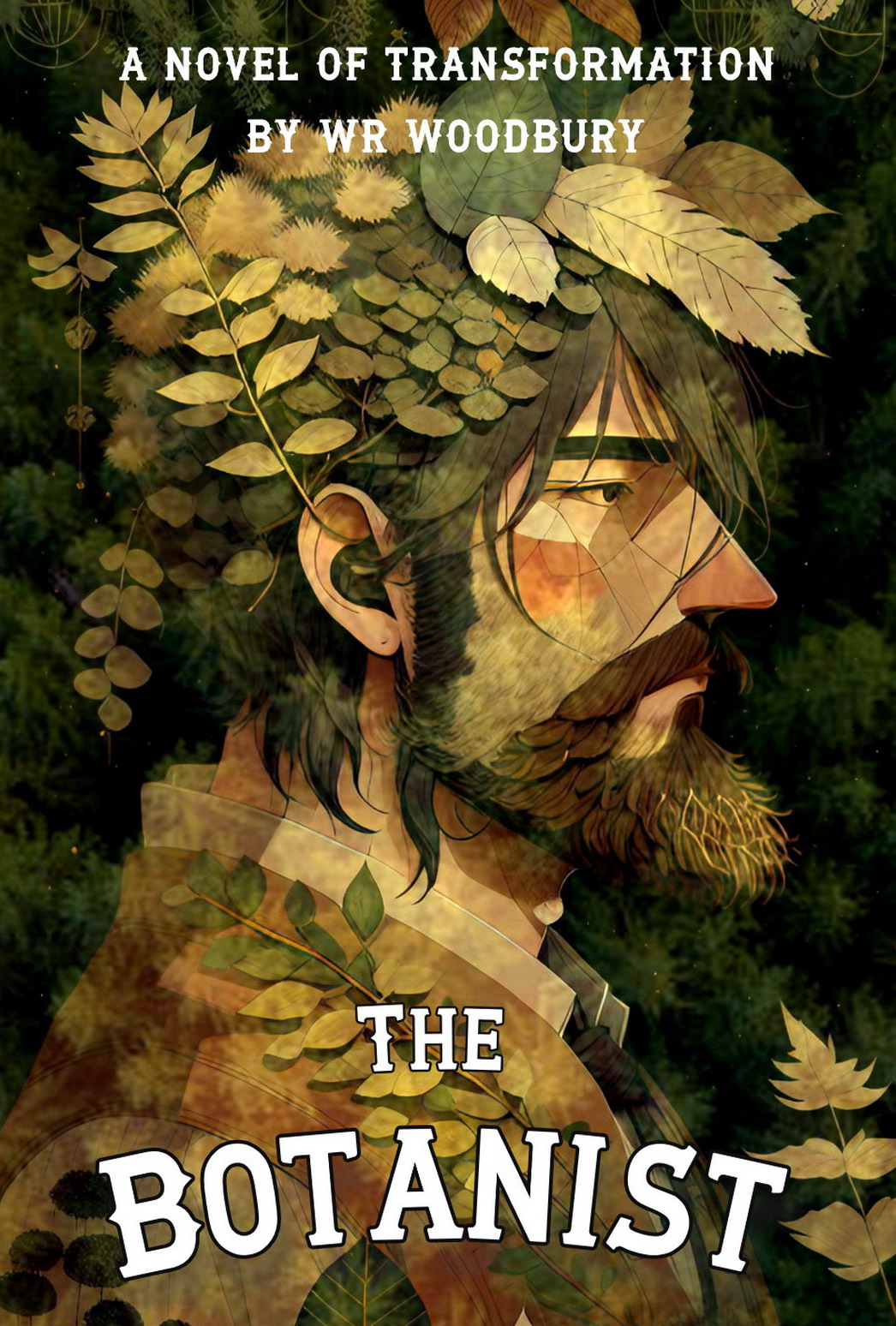

This Indie Corner revisits author W.R. Woodbury and his new novel The Botanist. In this seven episode work of literary fiction, a young man partakes of psilocybin mushrooms with a native shaman in the Pacific Northwest, and discovers that he hears voices from plants and sees disturbing visions in certain trees. Pursuing a growing interest in botany across several continents, he encounters hashish producers and pederasts in Morocco, orchid collectors in Singapore and Florida, corrupt financiers and beautiful women in London, political extremists in Athens, drug smugglers in Milan, and a group of Tuscan Egyptologists, all while conducting his plant research. As he struggles to understand a series of mystifying visions, his skin goes through unusual changes that make it susceptible to climate and stress. On his last adventure he suffers a devastating punishment for misusing what he has come to understand as his special powers. These stories explore the possibility and impossibility of crossing cultures and ultimately, species.

Mary: What inspired you to write The Botanist?

WR: There were several events that led to the writing of this book. One of them was reading a review of Sheila Heti’s 2022 Governor General’s Literary Award winner, Pure Colour. A character in the book deals with a loved one’s death by becoming a leaf for about 40 pages. My first thought was that this was absurd. “You can’t do that.” Once the idea had sunk in, I began to ask myself, “Why not?” One of the joys of writing is being able to create stories that are limited only by the writer’s imagination. Shortly before starting The Botanist, I wrote a book of short stories called To The Pips in which I tried writing from unusual points of view, including that of a dog and a cat. Although The Botanist doesn’t have an unconventional point of view, the idea of getting inside a leaf freed me up to put my own mind inside trees and plants. Writing The Botanist was also influenced by my work in the forestry industry and as a professional and amateur gardener. The book is divided into 7 episodes, a form that was influenced by the structure of Netflix series. Each episode is a story in itself, though there are some characters who reappear. I have made notes for at least an 8th episode, and if time and interest merit the work, I could go on with it and more.

Mary: The premise is so interesting: an ethno-biologist traveling around the world learning about how and what locals grow for food and, sometimes, drugs. Your own travels must have influenced this book! Your writing feels knowledgeable, and I felt every bit immersed into the places you write about. How did your personal experiences help you when writing this book?

WR: The episodes are set in a variety of locations worldwide, and though I have been to all of the countries where the stories take place, I have not been to some of the specific locations, like Townsville in Australia or Palm Beach, Florida. Although a lot of research goes into making sure the details are correct (the Internet is a priceless tool for writers), there is nothing like having personal experience of a place to help in creating atmosphere. Some of the episodes in The Botanist touch on the subject of traditional foods that indigenous people have collected for thousands of years, but thanks to commercialization, destruction of native habitats, and newer generations who are more interested in fast food and sugar, traditional foodstuffs that required only gathering and no cultivation are disappearing as options for survival.

Mary: The book feels fast-paced and full of suspense. Each chapter shares threads with other chapters, but the chapters themselves felt like vignettes in the main character’s life. It kind of reminded me of James Micheners’ The Drifters. What are your thoughts?

WR: As for similarities with James Michener’s The Drifters, it was published in 1971 and has Torremolinos in Spain as one of its principal locations. I lived in Torremolinos in the winters of 1968 and 1969 when I was in my early 20s, so it was my generation and milieu he wrote about. A book closer to The Drifters would probably be my memoir, Io Vagabondo. Besides Torremolinos, The Drifters moves from Spain, to Portugal, Mozambique, and Marrakesh, so the idea of traveling wherever the wind takes you is something it has in common with The Botanist.

Mary: An unusual transformation is also taking place in the book. Can you talk about this without spoilers?

WR: The protagonist’s transformation takes place over the course of the book. Recognizing that all living things are subject to change as they grow, the botanist uses his scientific knowledge and awakened senses that have been augmented by mind-altering drugs to understand plants and how they communicate. The more he connects with the green world, the more he notices changes in himself that are similar to changes in plants. At first hesitant about his perceptions, he is eventually amused by the idea that one day he may be more plant than human. He accepts this transformation as interesting and natural.

Mary: I know that you’re into climate and ecological changes, just like I am. How does your book relay this?

WR: Although I am interested in what happens with climate and ecological changes and how we humans live in the middle of it, The Botanist is a more personal story than my earlier novel, Boneyard Highway. That one is set in a road construction camp in the isolated north when there are altered climate conditions, cities are being abandoned, and those who go out in the sun, when it makes a rare appearance, get badly burned. The Botanist takes place in the late 1970s. Silent Spring had been published only 15 years earlier, but by the end of the 1960’s, thanks to the back-to-the-land counterculture movement, we understood that animals, humans, and plants, are all part of a linked system, and that harm to one brings harm to the others.

Mary: Anything else you want to add?

WR: Every gardener knows that plants have specific needs and, with centuries of traditional gardening practice, a gardener might still ask a plant, “Where would you grow best?” Anyone who has repotted a plant understands the feeling of gratitude when growing conditions are improved. I have seen plants fail because of what professional gardeners might call psychological problems, which in more prosaic terms means the plant is not happy in its surroundings. The factors that influence the plant could include light, soil quality, humidity, and habitat. Plants can’t move to give themselves a better chance of survival, but through seeds and roots they can travel and, like humans, over time they find the conditions that allow them to thrive and live productive lives. We think of plants as non-sentient beings, but the truth is we are only now learning how to understand their language. This novel explores some of the pathways of communication between species and suggests there could be physical changes in each as a result.

Mary: Thanks so much! I thoroughly enjoyed this book and recommend it!

W.R. Woodbury was born and raised in British Columbia and spent half of his adult life living and working in places like Greece, Italy, Germany, England, and Australia. He has been a librarian, forest-fire fighter, highway surveyor, banker, tour guide, night auditor, taxi driver, gardener, postman, ranch hand, stained glass artisan, draftsman, hotel manager, and courier driver. He retired from regular work in 2018 to devote more time to writing.