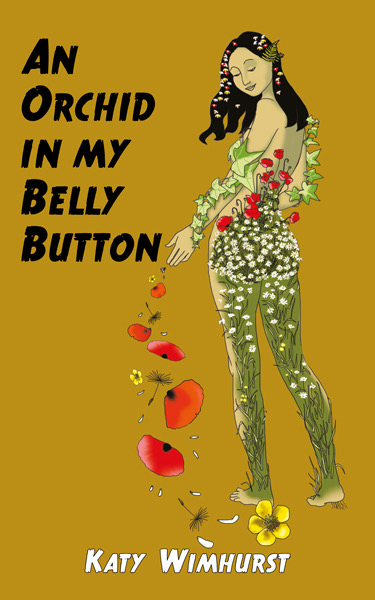

Katy Wimhurst has had three collections of short stories published—An Orchid in My Belly Button (Elsewhen Press, 2025), Snapshots of the Apocalypse (Fly on the Wall Press, 2022), and Let Them Float (Alien Buddha Press, 2023). Her first book of visual eco poems was Fifty-One Trillion Bits (Trickhouse Press, 2023). She sometimes interviews writers for 3AM Magazine. More about her can be found on her website. She is housebound with the illness M.E. Her newest anthology is described as “offbeat short stories that explore our fragile world.”

Katy is donating part of her royalties from An Orchid in my Belly Button to an environmental charity. The stories savour the surreal, flirt with magical realism, and dabble with dystopia. A boy sees the ghosts of dead crabs. A girl with a fox tail is bullied. A disenchanted woman sprouts orchids from her belly button. Fashion models pursue the trend of having plants as hair. Electronic goods amassing all over London herald an apocalypse. Darkness and wonder, the strange and the ordinary, interweave to offer an environmental and social portrait of our times. Guaranteed to evoke a response, whether a giggle, a gasp, or a nervous gulp, these stories will stay with you, enriching your perception of the world.

Mary: Hi Katy, and welcome to Dragonfly. Tell us about your new book and what inspired it.

Katy: An Orchid in My Belly Button is a short story collection that includes magical realist, surrealist, climate fiction, and dystopian stories. I didn’t set out to write a collection but when I put it together, it seemed obvious to organise it around themes of nature and the environment because so many stories I write are inspired by those. The climate crisis is something I am preoccupied by, yet there is so much apathy and ignorance about it in our society. I see fiction as a way of addressing some of the issues in a way that engages and isn’t preachy — despite bleak themes, I try to inject quirky imagery and wry humour to make the stories engaging to read. Several tales in the book examine the climate crisis in a metaphorical or speculative way—for instance, in ‘The Blind Ark’ a wealthy, privileged couple who retire on a yacht develop a compulsion to buy more and more things, with unfortunate consequences; in ‘Nothing Like Ice Cream in the Apocalypse’ electronic goods start piling up in the streets all over London, signalling an apocalypse, yet many people seem to want to ignore it; and ‘The Carp Whisperer’ is set in a world of scarcity.

Mary: How does your book align with nature?

Many of the short stories in An Orchid in My Belly Button include nature as a theme. “The Mushroom Lovers” features oyster mushrooms growing from an elderly woman’s arm; in “The Ghosts of Crabs”, a child sees the ghosts of dead crabs killed by environmental pollution; “Vanity Vines” explores the trend among social media influencers of having plants as hair; and in “Fungi, Friends, Family”, an eco commune in the near future flourishes by producing materials made out of mycelium. In each story, I reflect on the human relationship with the natural world through a different, speculative lens. As the writer Nalo Hopkinson says, “Speculative fiction is a great place to warp the mirror, and thus impel the reader to view differently things that they’ve taken for granted.”

Katy Wimhurst’s stories give me that same sense of strangeness and warmth that I got when I was young from some of Gabriel García Márquez shorter tales, and by “warmth” I don’t mean to suggest that these are all feelgood fictions but that the prose in which they are written glows. The style is fully flowering, a joy to read, a delight to ponder, perfectly adapted to the embodying of the author’s filling and nourishing narratives. Simply stated, these are excellent stories. They seem almost organically grown, enveloping the reader in the tendrils of their telling. There is precision here too, but it is never angular. This is a superb book by a wonderful writer. And it’s not Magic Realist in the flowery sense, despite the blooms of the title story, but realistically tough when it needs to be, filled with the alienating situations, circumstances and bewildered people of the contemporary world. Hard to choose a favourite when the book is so tightly integrated with itself but ‘The Blind Ark’ has lodged itself very firmly into my mind. A magnificent collection. –Rhys Hughes, author of The Devil’s Halo.

Mary: What other writers and books do you read?

Katy: I read in different genres, but I’m a huge fan of magical realism. There is something playful, a lack of constraint, about the genre, and I love the way it creates concrete metaphors to address themes (if you want a woman haunted by thoughts of her mother, just toss in the actual ghost somewhere). There are so many brilliant books in this genre: One Hundred Years of Solitude, Men of Maize, Midnight’s Children, This One Sky Day, Beloved, and Siddon Rock. I like how many of the books come from the cultural periphery rather than the centre and how the genre is often implicitly political, giving voice to marginalised groups, whether indigenous peoples, migrants, women, non-westerners, etc.

Mary: What’s your greatest experience in nature that profoundly affects your work?

Katy: I am completely housebound with a chronic illness, but fortunately my flat overlooks a tidal river. Without that view, the woods in the background, and the sky above, my life would feel significantly more restricted. I am appreciative of it, and I am fascinated by how the river, including the colours on its surface, is constantly changing, and how different birds appear in different seasons. When you are ill, you are forced to slow down and become more of an observer, and I hope that quality infuses my writing somehow. I like to use detail in my fiction to bring the characters and settings to life. I listened to the renowned British writer Susanna Clarke, who coincidentally has the same illness as me, talk in a podcast about the process by which her book Piranesi (and its titular protagonist) were influenced by her own chronic illness. She said when you are ill, you learn to take pleasure in what is available to you, even if it seems at first limited, and what is available to you expands rather as you contemplate it. In the book, Piranesi’s life is limited, but he takes immense interest in what surrounds him—the statues, tides, and the birds in the vast House. Clarke sees this attention towards the world as the type of magic that infuses the book, as opposed to the fantasy type of magic she used in her first book, Johnathon Strange and Mr Norrell. I like her idea that magic can lie in paying attention to ordinary things, illuminating them through the power of observation. I like to think something like that pervades parts of my writing too.

Mary: What led you to the creative outlet of writing?

Katy: I probably wouldn’t have written fiction if I hadn’t got chronically ill in my 30s. I would have continued in academia or moved into curatorial work and written books on art. When first severely ill with M.E.—which is a hugely disabling illness (even if many medics trivialise it)—I was way too ill to do anything creative. However, I was fortunate in that my cognitive abilities gradually improved to a level where I was able to start writing short fiction. Writing stories was fun, a focus for imagination, and I enjoyed working at improving my craft. In my opinion, creative writing is more craft than art. Although I had a severe relapse in 2019, it is my physical functioning that has been affected more than my cognition, which means I can continue writing, albeit slowly.

Mary: What’s next for you?

Katy: The novella I am currently writing is a magical realism story with environmental themes. It is partly inspired by a true-life incident, the washing up of thousands of dead crustaceans on a beach in northern England. It is a story that encompasses political corruption, and emotional and environmental toxins. It is told from the point of view of both a mother and her eleven-year-old daughter, who respond to the crustacean deaths in distinct ways.

Mary: I’m looking forward to what’s next. Thanks so much, Katy, for sharing your new anthology and part of your life story.