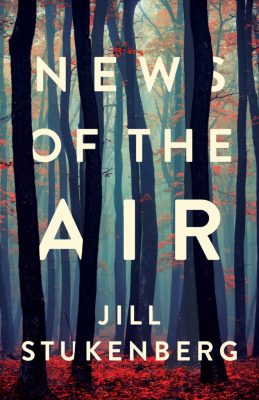

I’m so happy to welcome Jill Stukenberg to the Indie Corner and discuss her new novel News of the Air (Black Lawrence Press 2022). During our email exchange, I found some commonalities, including our love for northern Wisconsin, a place that also shaped my youth.

Jill’s novel News of the Air won the Big Moose prize from Black Lawrence Press. Her short fiction has appeared in Midwestern Gothic, The Collagist (now The Rupture), The Florida Review, and other places. She is co-editor of Midwest Review and an Associate Professor of English at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point. Learn more at https://jillstukenberg.com, follow her Facebook page Jill Stukenberg author, or find her on Twitter at @jillstukenberg.

Mary: Tell us more about you, what you do for a living, and your hobbies.

Jill: I grew up in Wisconsin and have lived and taught in the Southwest and Pacific Northwest, and now I’m back in my home state, working as an Associate Professor of English at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point and as a mom. In that first role, I get to do things like teach Intro to Creative Writing and Composition courses, and I’m co-editor of the literary magazine Midwest Review. In the second role, I play a lot of Pokémon and enjoy knock-down, tackling snowball fights. I like to ski and sail and hike, and be anywhere near trees.

Mary: What sorts of things ran through your head that led to the writing of News of the Air?

Jill: This novel takes place in a near-future northern Wisconsin. A family who has grown uneasy living in the city has moved to the Northwoods where they think life will be easier and safer. That concept—the idea that the natural world around us is changing, and slowly altering human society in macro ways and individual families in micro ways—drove this book. I will confess, though, that I didn’t know about the term eco-fiction until much of the story was finished and I was trying to think of how to describe it to would-be publishers and readers. In writing it, I also thought about the forces that push and pull families apart, including a child growing older, with the possibility of their leaving home, which is even more of a question in rural places, I’ve come to believe. I was also interested in cell phones and technology as forces in family and community life, and political divides. Basically, there’s all that in the book—and kangaroos too, as one book club reader exclaimed to me.

Mary: Describe what’s going on and the kind of world happening around the main characters.

Jill: Eighteen years have passed since a pregnant Allie Krane and her husband Bud moved from the city to Northern Wisconsin. Situated in a somewhat remote place, and isolated further by other choices (they home-school their only child, and no guests visit their small resort in winter), they are not as directly affected by events in the cities—and when they hear of them, it is through summer visitors who have themselves become inured to homelessness/refugee crises, water shortages, pollution, brown-out days, new border checks, and even shocking political protests involving teenagers setting themselves on fire. They themselves have witnessed—at times, and over the years—a turbulent local economy, some seasons of more wildfires and spring flooding (but some seasons with fewer of these), and teenagers who feel hopeless about the future. Allie and Bud develop a difference in opinion about these changes, too, including how significant they are, what they mean, and how they should respond. Should they sell the resort and move? Is now the time to hunker down and stay?

Jill: Eighteen years have passed since a pregnant Allie Krane and her husband Bud moved from the city to Northern Wisconsin. Situated in a somewhat remote place, and isolated further by other choices (they home-school their only child, and no guests visit their small resort in winter), they are not as directly affected by events in the cities—and when they hear of them, it is through summer visitors who have themselves become inured to homelessness/refugee crises, water shortages, pollution, brown-out days, new border checks, and even shocking political protests involving teenagers setting themselves on fire. They themselves have witnessed—at times, and over the years—a turbulent local economy, some seasons of more wildfires and spring flooding (but some seasons with fewer of these), and teenagers who feel hopeless about the future. Allie and Bud develop a difference in opinion about these changes, too, including how significant they are, what they mean, and how they should respond. Should they sell the resort and move? Is now the time to hunker down and stay?

Immediately in the novel’s plot line, two strange children arrive by canoe, followed by a mysterious woman who says she is their grandmother, and Allie and Bud’s eighteen-year-old daughter Cassie is dealing with the death of a friend, a punishment that took her cell phone away for the summer, and her own increasing estrangement from her mother.

The book is somewhat odd for climate fiction or a near-future dystopia—though I hope in a good way; it was certainly an intentional way. There is not one giant calamity driving the collapse—like a pending meteor or virus. Instead, I wanted the book to play with what it feels like to live in a world that is slowly changing, and in ways we can’t always see or even agree about. Readers might finish the book and wonder: Was this a near-future dystopia, or does it depict reality now?

Mary: Do you think fiction can be a powerful way to get readers to think more about our natural world?

Jill: When writing engages our senses and immerses us in a place, that place becomes real to us and we become aware of characters (and maybe imagine ourselves) as beings who exist within that ecosystem. Setting is key in storytelling; Eudora Welty said that setting contributed the most to making a work of fiction believable, in helping the reader to enter a story, suspending their disbelief. So writers need to care about making that setting rich and real.

The other elements of fiction are character and plot. Works of fiction weave stories by combining character, plot, and setting—and time as a function of setting. So, as an artform, fiction puts people and their problems and choices into relationships with the places they live—and often when rendered realistically, and with care, those places are dynamic, affected by change and time. So I think that yes, writing and reading fiction is a fantastic way to think about the natural world that surrounds us, and our built world too (if there is a distinction there).

Finally, when the setting in a novel is specific and unique, I think that helps us to see the world—and all the natural and built places within it—as one of variety and of precious, irreplaceable niches.

Mary: Who were your favorite authors growing up, and did any of them have nature as a strong focus?

Jill: What a great question! I just realized how much L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables series probably operates at the base of my psyche, and of my love for the natural world and feeling like characters should be depicted as existing, at least some of the time, out of doors, or within seasons. (As a central Wisconsinite, it’s hard for me to imagine a character walking out their door without making a quick choice to grab a hat or not, and/or regretting whatever choice later.) I also loved Madeleine L’Engle’s work, and though some of it was interplanetary, it definitely taught me about connectedness and gave me a way of thinking about humans as existing within larger systems.

Mary: Is there anything you would like to add about this story?

Jill: I think there’s a way of seeing hope through my book too, for the characters and for us. That might sound strange given how I’ve described it so far, but I think it’s there.

And as a person living on this planet, in this real time, I see reasons for hope—even as I see the problems too.

Mary: Are you working on anything else at the moment?

Jill: I’m writing interconnected stories about people living in a rural place in Wisconsin. I can’t get away from writing about my home state and this region. It means something to me to write books that are set here, and to hope that readers here—along with readers anywhere—will find meaning and connection in that too.

Mary: Sounds great, Jill. Thanks so much for adding this wonderful book to our library.

As fellow Wisconsinite there is both veracity and deep affection in Jill’s descriptions of her setting and characters. It is a subtly distressing tale that simultaneously creates hope. Enjoy every lyric paragraph.