Back to the Indie Corner series

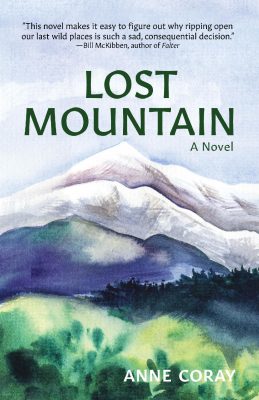

I’m thrilled to introduce author Anne Coray to the Indie Corner spotlight.

As a lifelong Alaskan, place has always helped define Anne. Born in a log cabin on Lake Clark (first named by the Dena’ina Athabaskans Qizhjeh Vena), she spent her first two years in a true wilderness setting. Later, she and her husband settled on the same family property, in a different cabin that they built together. For 17 years they lived there year-round; now they reside six months of the year at the lake and the other six months in Homer. The ways in which the lake, and Alaska in general, have influenced Anne’s writing are tremendous. Whether the subject is love or death or an environmental lament, often the Alaskan landscape serves as a backdrop. This intimate view of the natural world sometimes evolves to encompass historical events or meditations on climate change. Whatever her topic though, she feels that her duty is to language: sound and rhythm, metaphor and imagery, the making of music on the page.

Anne Coray’s poetry collections include A Measure’s Hush, Violet Transparent, and Bone Strings. She is coauthor of Lake Clark National Park and Preserve and co-editor of Crosscurrents North: Alaskans on the Environment. Her work has appeared in many literary magazines including the Southern Review, Poetry, and North American Review. A finalist with White Pine Press, Carnegie Mellon, Rooster Hill Press, Water Press & Media, and Bright Hill Press, she has several Pushcart nominations and had received fellowships from the Alaska State Council on the Arts and the Rasmuson Foundation.

Mary: Hi Anne, and thanks for joining us at Dragonfly today. Tell us about yourself—your life so far and how you got started in writing. What else have you published besides Lost Mountain?

Anne: First of all, thank you Mary, for all you do. The dragonfly eco-fiction site was such a wonderful discovery for me. It’s an important resource full of valuable information.

Mary: Thank you!

Anne: Writing and the visual arts have preoccupied since grade school. I earned my undergrad degree in art but then went on to pursue writing and an MFA as an adult. My focus was poetry for many years, but I wanted to take on a larger project and appeal to a different readership. So I ended up writing my debut novel, Lost Mountain. I love language—the sound of words, cadence and tone, use of assonance and alliteration—all the tools writers have in their toolkit to make the written page come to life. After publishing three full-length collections of poetry (Bone Strings, A Measure’s Hush, and Violet Transparent) and an anthology of poetry and prose that I co-edited, titled Crosscurrents North: Alaskans on the Environment, I turned to literary fiction. That doesn’t mean I’ve completely abandoned poetry though. I recently wrote a 24-poem linked sonnet sequence with interwoven themes of fire, climate change, art, and myth.

I’m a lifelong Alaskan, and my husband and I lived 17 years at my birthplace on remote Lake Clark as adults. This is roadless wilderness, accessible only by small aircraft. Part of Lake Clark National Park & Preserve, the rugged, mountainous terrain makes it a truly scenic area of Alaska. We now divide our time between the lake and Homer, a small coastal town on the Kenai Peninsula. Homer is another beautiful landscape. It’s no wonder that the natural world has weighed heavily in my writing.

Mary: Tell us something about your newest novel. Who is the intended audience, and what’s going on in the story?

Anne: Lost Mountain was written with the intent of reaching a wide range of readers. Certainly I want people from the environmental community to read the book, but I’m also hoping to tap those readers who are simply looking for a good story. I wanted to personalize the threat of a large-scale development project. That’s why I focused on characters, and I tried to sprinkle the issues throughout the book so they didn’t become too concentrated. It’s tough, I think, to make people realize that an environmental theme doesn’t necessarily slot a book into a category—it’s possible for literature to entertain and convey human elements while still sending an important eco-message. So I especially appreciated this from one reader’s review: “I have to admit I approached the book with concern that the politics might weigh heavy on the story, but I was very pleased to see how creatively the author pulled all the elements together to produce an engaging read.”

Anne: Lost Mountain was written with the intent of reaching a wide range of readers. Certainly I want people from the environmental community to read the book, but I’m also hoping to tap those readers who are simply looking for a good story. I wanted to personalize the threat of a large-scale development project. That’s why I focused on characters, and I tried to sprinkle the issues throughout the book so they didn’t become too concentrated. It’s tough, I think, to make people realize that an environmental theme doesn’t necessarily slot a book into a category—it’s possible for literature to entertain and convey human elements while still sending an important eco-message. So I especially appreciated this from one reader’s review: “I have to admit I approached the book with concern that the politics might weigh heavy on the story, but I was very pleased to see how creatively the author pulled all the elements together to produce an engaging read.”

Lost Mountain is a love story set in remote Southwest Alaska in a fictional artists’ community called Whetsone Cove. It’s told in alternating chapters through the eyes of two protagonists, Dehlia Melven and Alan Lamb. Dehlia, a mask carver, is overshadowed by loss and uncertainty of her future security; the recent death of her husband and a contract that demands she wait two more years before acquiring ownership of her home makes her cautious. Alan, a solar tech, is the opposite: engaged, outgoing, and too prone to express his views, he sometimes oversteps his bounds. When a huge open-pit mining project threatens the serenity of the town and the salmon they depend on, the characters must come to grips with what they stand for.

Mary: Sounds so interesting. Can you expand on the ecological themes in the novel?

Anne: The mining threat in Lost Mountain is inspired by the Pebble Mine prospect, a very real and very ugly development project that threatens the entire Bristol Bay watershed and the greatest wild salmon fishery left on the planet. Although reference is made in my book to commercial fishing in Bristol Bay, the people in Whetstone subsistence-fish for salmon.

The proposed mine site is about thirty-five miles from where I live on Lake Clark. My husband and I started hearing rumors about Pebble in the early 2000s, and within a few years it was way more than a rumor. We started paying a lot of attention. We read newspaper articles and scientific reports and learned about open-pit mining, which was something we were totally unfamiliar with. Pretty soon the Pebble Mine was looking like a very real threat. All this became the background for Lost Mountain. Of course, the names of the mine and the mining company are fictitious in my book.

Lost Mountain also references climate change. In the time that I lived year-round at Lake Clark I saw a gradual increase in temperatures, so much so that the lake would sometimes not freeze over in winter. Higher water temperatures have negative effects on salmon, especially red salmon, which thrive best in cold glacial water.

Mary: Having lived for several years in British Columbia and volunteering with river organizations and wild salmon populations, this story (and reality) appeals to me greatly.

After publication, did you do any book fairs or talks? How would you describe the reaction to your book? Is it hard to market during the coronavirus?

Anne: I’ve done several Zoom events to help promote my book. I’ve discovered that I really like using PowerPoint, because people enjoy seeing images, especially photos of Lake Clark. My first event was with Alaska Wildlife Alliance. I was one of three presenters. I talked about my book and read short excerpts, another presenter discussed beluga whales, and a third talked about brown bears. My second event was through The Alaska Center. It was titled “A Passion for Salmon: Art and Advocacy.” I, along with three visual artists, talked about our work and how the arts are effective messaging tools on behalf of the environment. Then I did a third presentation with me alone for a local group called Alaska Professional Communicators. In that talk I gave some personal background, read from my book, and talked about nature writing and eco-lit and how I distinguish between the two.

I have two more events scheduled as of this writing: one through Pubwest/ Bookbar in Boulder, CO, and another through the Gallery Bookshop in Mendocino, CA. These will be with other authors as well. I enjoy collaborating for these events; I think viewers like to hear from more than one speaker.

In many ways I think doing online events is easier than in-person. Not having to travel is a big part of that. And as I mentioned, the PowerPoint format suits me. Being a non-tech person I find it relatively simple to present this way from my home computer. Plus, limiting travel is unarguably better for the environment. Less burning of fossil fuel! That’s not to say that I wouldn’t occasionally enjoy face-to-face contact again.

As for reaction to my novel, I’m pleased thus far, but I’d love to hear from more readers I don’t know personally.

Mary: I agree that in these very strange times, not burning fossil fuels to promote ecological art and fiction is so important. Are you working on anything else right now, and do you want to add other thoughts about your book?

Anne: I have another novel manuscript that is close to being ready for an eager publisher. The setting is much the same as that of Lost Mountain, but the place names are different. The single first-person narrator is Jenny, an independent young woman with a background in theater arts. She is caring for her older brother, Terrence, who is compromised by mental health issues. Jenny establishes a small community on the homestead where she and Terrence live. A mysterious illness appears among the residents. Naturally, the human health component of this novel echoes the many environmental concerns I’ve been preoccupied with over the years.

I’ll close by saying one more thing about Lost Mountain. Very few novels cover the subject of mining, especially open-pit mining, and this makes the book unique. It’s a topic that needs more exposure in the literary landscape.

Mary: I agree. There aren’t too many novels covering mining specifically. Also, the newest novel sounds interesting. Thanks so much for talking to me about your novel, background, and wonderful experience!