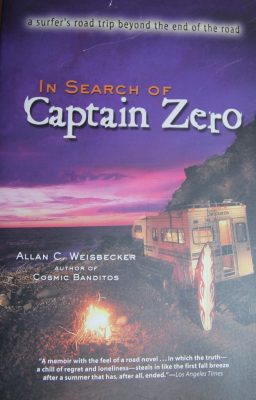

The story behind this book is that I discovered it when I lived in California. I wish I could remember where I found this book, but I just can’t remember. The important thing is that I found it somehow, likely at a bookstore or surf shop, and from the minute I began reading I was hooked. The photo here is of my copy of the book, which is now 14 years old. You can’t see the worn edges, because I was trying to do a nice crop job, but this book went with me to the beach, into bed at night, and everywhere. I actually read it in a week and then re-read it. It meant a lot to me at the time because I was a wreck due to a bad relationship and needed to do some things to get myself out of that. I began hiking with coyotes and running into rattlesnakes in the hot California sun, and developed a life-long love of the ocean. I learned that sun, reading, water, and getting outside were better than indoor self-pity.

The story behind this book is that I discovered it when I lived in California. I wish I could remember where I found this book, but I just can’t remember. The important thing is that I found it somehow, likely at a bookstore or surf shop, and from the minute I began reading I was hooked. The photo here is of my copy of the book, which is now 14 years old. You can’t see the worn edges, because I was trying to do a nice crop job, but this book went with me to the beach, into bed at night, and everywhere. I actually read it in a week and then re-read it. It meant a lot to me at the time because I was a wreck due to a bad relationship and needed to do some things to get myself out of that. I began hiking with coyotes and running into rattlesnakes in the hot California sun, and developed a life-long love of the ocean. I learned that sun, reading, water, and getting outside were better than indoor self-pity.

Allan Weisbecker seemed to be a genius writer: his every word hit me somewhere, from his sadness over loved ones’ illnesses or deaths, to his deep care for his dog, to the selling of most of his possessions and just taking off to find an old friend somewhere in Central America and along the way trying to find that perfect wave at every beach. Weisbecker, who had written for “Miami Vice” and done a few other really cool jobs like that, became a hero to surfers world-wide as well as expatriates, because he set out for the “end of the road” (Pavones, Costa Rica). Allan, who has become close to getting movie deals (but just “doesn’t get along with anyone”), wrote to me after I published a review of the book, and we kept in touch for a while.

Later, when I first got to talking to the man who would become my husband, he asked me what my favorite books were, and I told him. In Search of Captain Zero was number one at the time (and still might be, though favorites are tough). My future husband loved it too, which earned a lot of points for me.

I will copy my review of the book (previously published at Jack Magazine in the summer of 2002) here and look forward to adding this book to my lost library.

Allan Weisbecker recounts his travels to Central America to find an expat surfer friend named Christopher who’d trekked the same path and “direction of vanishment,” and who Allan had last heard of three years prior via a simple postcard with the signature “Capitán Cero”. It is a true story of the perpetual search for the perfect wave and for paradise, the eternal friendship between two men who’d years before traipsed around the world to surf and smuggle drugs. It is a story of a man’s compassion for the sea, his dog, and the colorful people and places he encounters. It’s a tale of pain, love, beauty, and risk. The accounts of Allan’s experiences and thoughts during his two-year travels in Mexico and Central America are vivid and heart-wrenching at times. I couldn’t put the book down once I picked it up, and it involved 3:00 a.m. blurry-eyed reading–sometimes simply from me being tired and sometimes from the emotional transcendence that escapes from author to reader.

If you’ve ever surfed, you know that waves can be frightening as well as intensely joyful. There are a few people to whom surfing is not just a lifestyle, as Allan says, but a life. Allan is one of these people. From the territorial dominance in a lineup to the ultimate grace on a longboard to the fear of big wipe-outs and sharks, Allan leaves nothing out about a surfer’s dilemmas and fulfillment. All the pleasures and fears surface as visually potent as the drama played out in Endless Summer, and you get the sense that another of Allan’s crafts, photography, has enabled him to capture with words the still frame, the moment, the flash of white-water or the glassy ocean.

Among the mangroves in Mexico and Central America, Allan documents through journal entries a biography of his vanishment, while recalling jaunts with his three-decade-long friend Christopher as they smuggled marijuana in order to fund their many trips to world beaches, such as Hawaii, North Africa, France, and Australia. Now, having done away with the frightening, illegal, sometimes humorous escapades, Allan quits his job, stores most his possessions, and moves from his home in Long Island to the bandito jungle of El Sur. He takes only the essentials: his faithful dog Shiner; his Ford–La Casita Viajera, or the little house that travels; surfboards; and a few other basic necessities. What he encounters is parallel to Jack Kerouac’s search for paradise in On the Road and Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness trip back through the river of time to the heart of horror. What lies in horror, though, is sometimes absurdly lifting.

It’s like Bruce Brown meets Colonel Kurtz.

In his lonelier moments, Allan documents how it is to have loved but never married, to have found a friend who’s gone through mysterious changes, and how it is to simply be by yourself and depend on good surf and moments with other migrants to keep your sanity, if not lift you up completely. Among the scares of muggers, scorpions, snakes, screaming howler monkeys, and crack-heads, Allan tries to find the clarity of his heart and beingness. From recollecting the tale of a surfer friend who’d quickly hopped on planes and driven up and down coasts to surf one hurricane’s resulting waves–a cosmic proportion to breathing a butterfly wing’s subsequent currents of air–to likening the liquid warmth of the womb to one’s origins, he leaves no area untouched when it comes to the physics, emotions, language, biology, chemistry, culture, and knowledge of the world according to a surfer:

Finally, as the physicists now tell us–and as Eastern philosophers have long implied–the “stuff” of matter is waves, if on the tiniest and most ephemeral of levels. The universe vibrates in many ways, and on many planes, producing many different realities: from vibrations of nothingness (of space itself) spring galaxies and stars and planets and human beings; similarly, from the sea’s vibrations arise groundswells that traverse the limited physical realm of our world. And perhaps consciousness itself–the universe turned inward to reflect on its own vibrations–manifests itself as yet another plane of vibration. Another sort of wave. (35-36)

Contrast the external realizations to the internal ones:

I imagine my father kissing my forehead each night at bedtime throughout my happy youth, saying, “Good night, sweet prince.”

And then I remember that my father lives in utter squalor with his cats as his only company, and that I have abandoned him.

Abandonment. It’s what I do best. (312)

External becomes internal. The curling stuff of waves.

In Search of Captain Zero, I want to say, is a book for our times. But it’s really a timeless book. Written with the spectacular prose of mind and sea, Allan Weisbecker’s memoir is no doubt a classic that will go down into history if only our times weren’t so lacking of true merit–underscored by a handful of media who advertise the most-common-denominator books instead of real phenomenal things. Maybe we’ll be lucky and the book will become widely read, and understood at whatever profound level the reader is willing to unlock. People could use this book, definitely employ it and enjoy it. There’s something here for everyone: surfer or non-surfer. The book essentially relates at every human level.

Having refrained from reading many books lately, or writing reviews, I knew a gem when I found it and buried other time-consuming matters in order to make myself sit in one place to do what I’ve done since age three: read. It was a pleasure, for this book in some ways brought me out of self-hiding, and made me feel like a great book should: alive again, ready for more, ponderous.

Allan Weisbecker is currently on his way back to Costa Rica, where he plans to write a sequel to Captain Zero. His website has ordering information, photos, and information on this book as well as his previous book, Cosmic Banditos.