Today, this site celebrates its 7th anniversary! I figured I’d give back to readers something I’ve been working on. But if not for you, these survey results wouldn’t be possible, so thank you!

Last autumn I had a chance to speak at Ecocity Vancouver about healthy socio-cultural subjects regarding climate change, which included the humanities. I chose the field of eco-fiction, since that’s my background, and my application to present was approved. I gave both an introductory presentation and a writer’s workshop. You can see my writer’s workshop summary here [PDF]. My last slide included links to a few of the many studies that have explored the concept of the individual, cultural, and societal impacts of reading fiction. I wanted to narrow these ideas down to ecologically oriented fiction and prose. So, I put out a survey and let it stay up for several months. The Ecocity presentations included prose, but the survey only included fiction (novels). This survey was casual, not affiliated with a college or university, nor inherently empirical (as this research does not involve testing or formal evaluation). In all, I had 103 responses and filled the survey out myself as well, wanting to contribute to the data.

Objectives

My goals for the survey were to start a conversation with readers about their experiences with, and ideas about, environmental fiction trends and impacts for both individuals and society at large. For this reason, the survey allowed readers to answer many of the questions in long-form. I also wanted to extend the humanities angle from Ecocity’s climate crisis theme by looking at how various novels approached ecological issues and how that contributed positively to culture/society. I wanted to explore how readers were affected by fiction (including environmental fiction) that they had read. What were their favorite novels of all times, eco-novels, characters? What did they like and dislike in such fiction? In what ways were they inspired by this fiction, and did they move to action–or how else were they socially impacted, either negatively or positively? What genres and subgenres did they enjoy the most? Did they think eco-fiction impacted society, and how? Though eco-fiction can also include poetry, films, games, short stories, and graphic novels (among other media), this survey stuck to questions about novels in order to stay focused as much as possible. A secondary objective was to help authors writing fiction about ecological issues to understand, according to at least this sample of readers, what works and what doesn’t work. How are readers impacted? What do they like in stories with ecology and environment at their core, and what turns them off?

Invitation

I invite people to share this data in small excerpts with credit to Mary Woodbury and with a link back to this survey summary at Dragonfly.eco. I’m also available for extending work on this survey in partnership with others. Please email me for more information. Note that participants’ names and contact information are private and will not be shared. Some long-form answers provided personal data about the participants, and that data also will not be shared.

Thanks

Thanks to Morgan Woodbury, my husband, for his support in this project and helping with data. Also thanks to Climate Cultures, ALECC Canada, ZEST Letteratura Sostenibile, Tools for After, and Goodreads Green Group for either allowing me a space to share the survey or for their word of mouth in helping to spread news of the survey. Thanks to numerous friends on social media who shared the survey with others. But, mostly, thanks to the 103 participants who took the time to complete this survey. Your responses are so important when it comes to exploring eco-fiction.

Survey Weakness

I feel that having a bigger audience would have shown more diversity in age, gender, and geographical data. Although I did not ask about respondent location in the survey, the audience of my social media, and those who helped share it, is primarily North American, European, and, to a smaller degree, Australian and South African; with more people on my social media sharing the survey, it seems more diversity could have been achieved, resulting in a stronger sample that might have improved demographics.

Time to Complete

The survey required some time to finish. It took me 17 minutes, but I had been thinking about this literature and the survey ahead of time. Many participants wrote in-depth answers to the questions. I anticipate that the survey took between 15-30 minutes to complete.

Question Types

The survey had 23 questions. Of these, 9 were multiple selection questions and 14 were open-ended (3 of the 14 were extended responses to other questions and were the only questions not required to answer). The first three questions dealt with demographics: age, gender, highest academic credential. The rest of the questions dealt with fiction, notable novels and characters, genres, and personal experience with fiction’s individual and societal impacts.

Data Collection

For several months, between early fall 2019 and early summer 2020, I posted the Google survey on social media, including Twitter (approximately 1,900 followers), Facebook pages (literature page: 941 followers; publishing page: 2,428 followers), and Dragonfly.eco’s website. The website’s visitor statistics are new, but the top 10 visitor countries in the last week were United States, United Kingdom, China, India, Canada, Germany, Australia, Brazil, France, and New Zealand. I also shared the survey via ALECC Canada’s newsgroup, Goodreads Green Group, Tools for After, and ZEST (see above for links). Climate Cultures posted the survey news twice in their monthly newsletter.

Data Consolidation

I had to duplicate the survey because originally it was a Google form that participants would need a gmail.com account to answer; 86 respondents filled out this form. I made an exact copy in Google forms that would allow anyone without a gmail.com email address to answer; 17 respondents used this form. After closing both surveys, I consolidated both forms’ data as .csv imports, so as not to corrupt number data into date data, etc. For long-form answers, I consolidated the data into ranges or common answers to present the data more clearly, but I will also give examples of long answers in the summary. For multiple choice answers, I transformed text into columns and preformed COUNTIF and SUM features in Excel to accurately calculate responses. Where “Other” was selected, I will also give examples of answers. I ignored long-form answers that were not relevant to the question (i.e. people wanting to promote their novels and using the long form to do that rather than answer the question at hand). For answers where blanks were filled with a single character, N/A, or not sure, I included that in the counts of data under N/A or equivalent. The latter types of responses were rare in this survey.

Data Summary

Please click charts and graphs to view a larger version.

Demographics

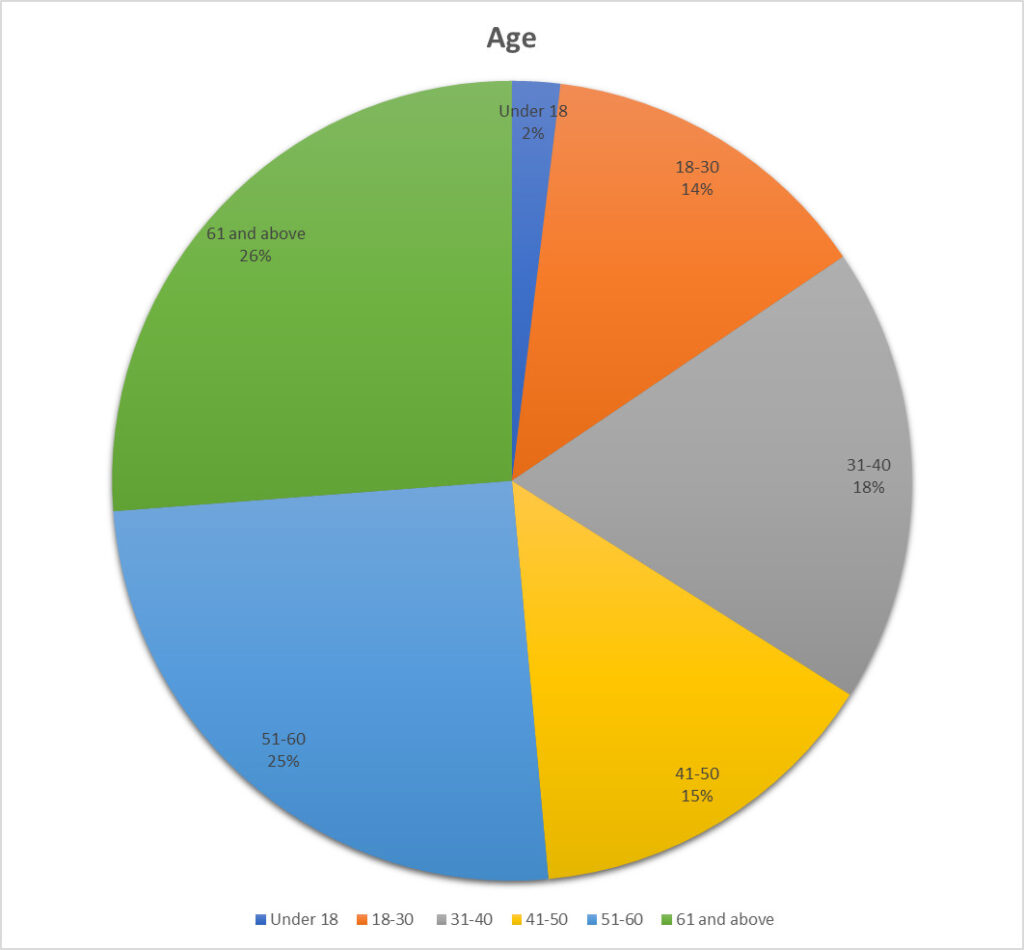

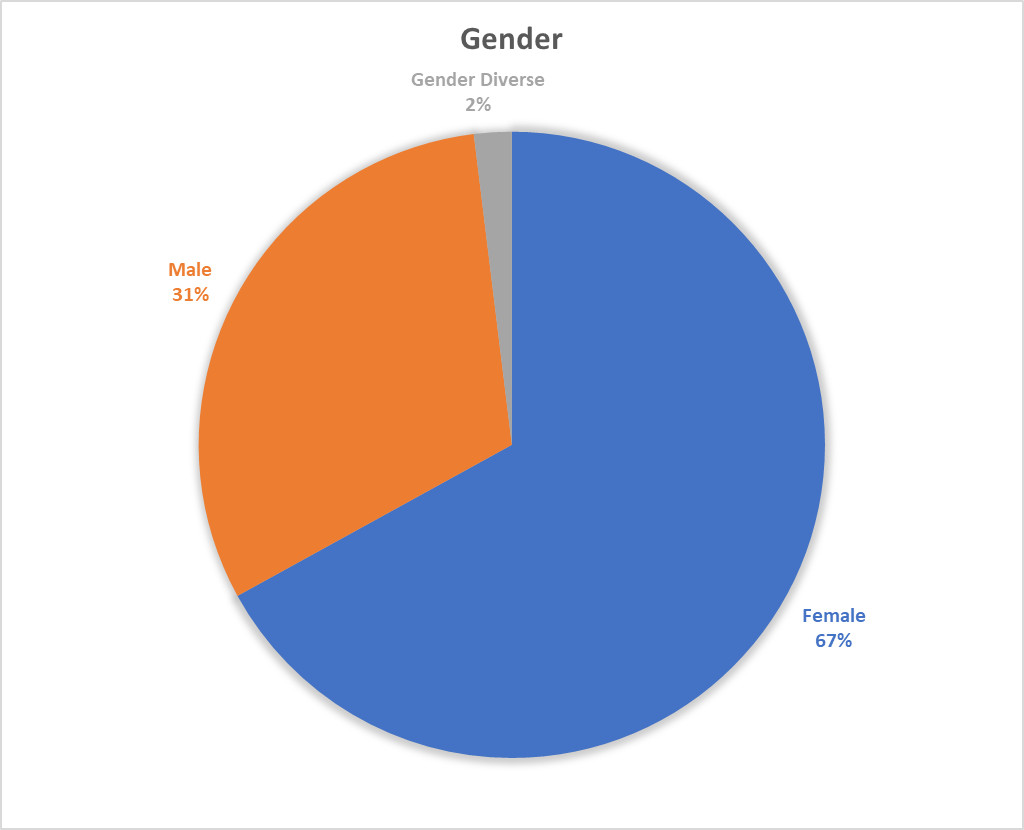

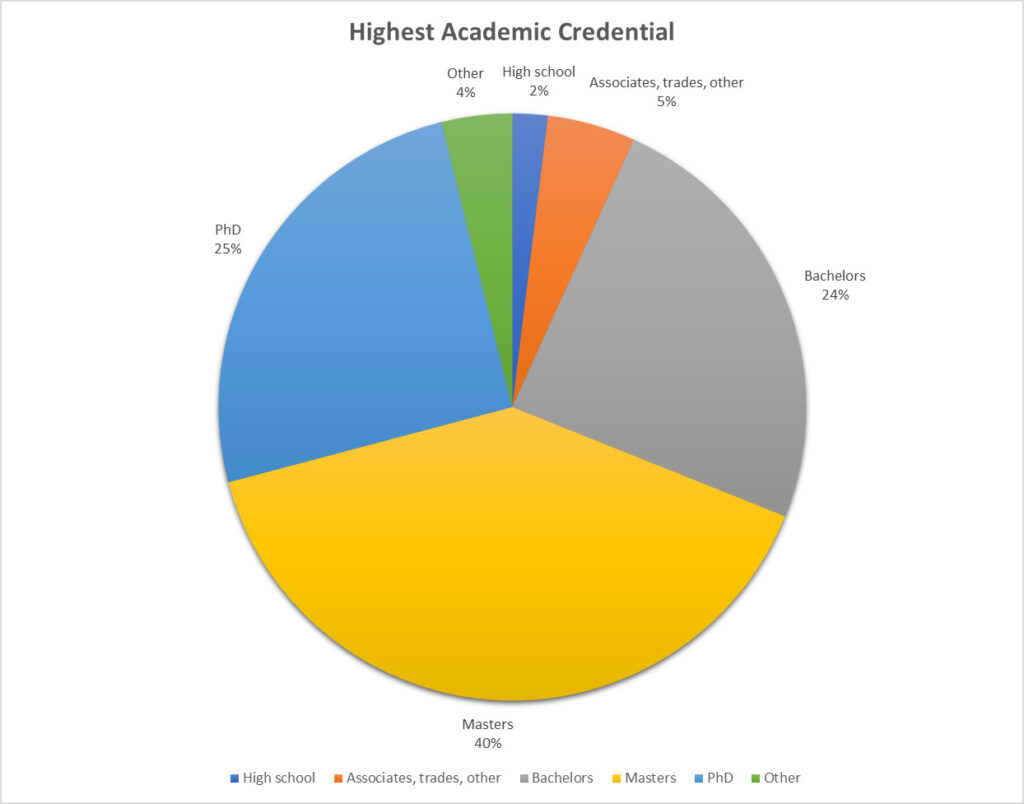

103 participants filled out the “Impacts of Environmental Fiction” survey. Of these participants, 26% were over the age of 61, followed by 25% 51-60, 18% 31-40, 15% 41-50, 14% 18-30, and 2% under the age of 18. Females comprised 67% of the participants while males made up 31%, and 2% were gender-diverse. 40% of the respondents had received a master’s degree, 25% a PhD, 24% a bachelor’s degree, 5% a trades or associates or other certification, 4% other, and 2% a high school diploma.

Age

Gender

Highest academic credential

Personal Reading Preferences

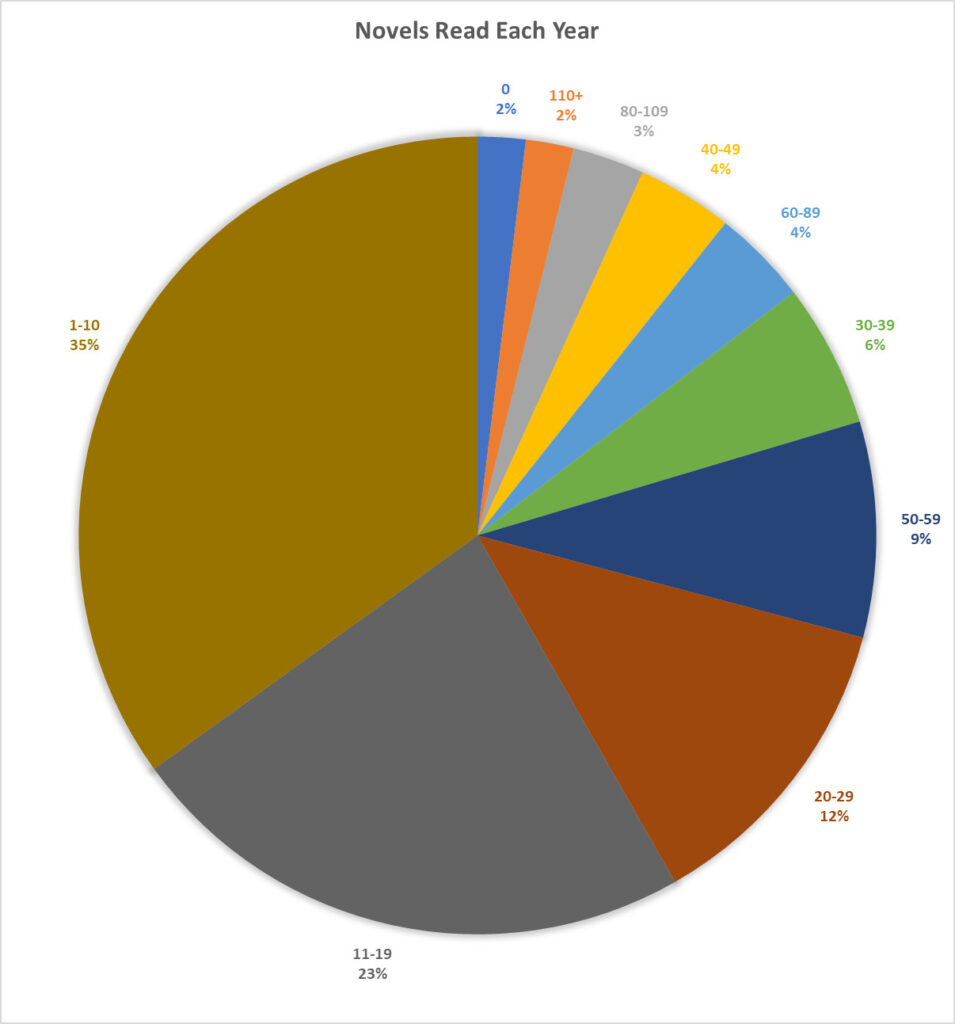

How many novels do you read a year?

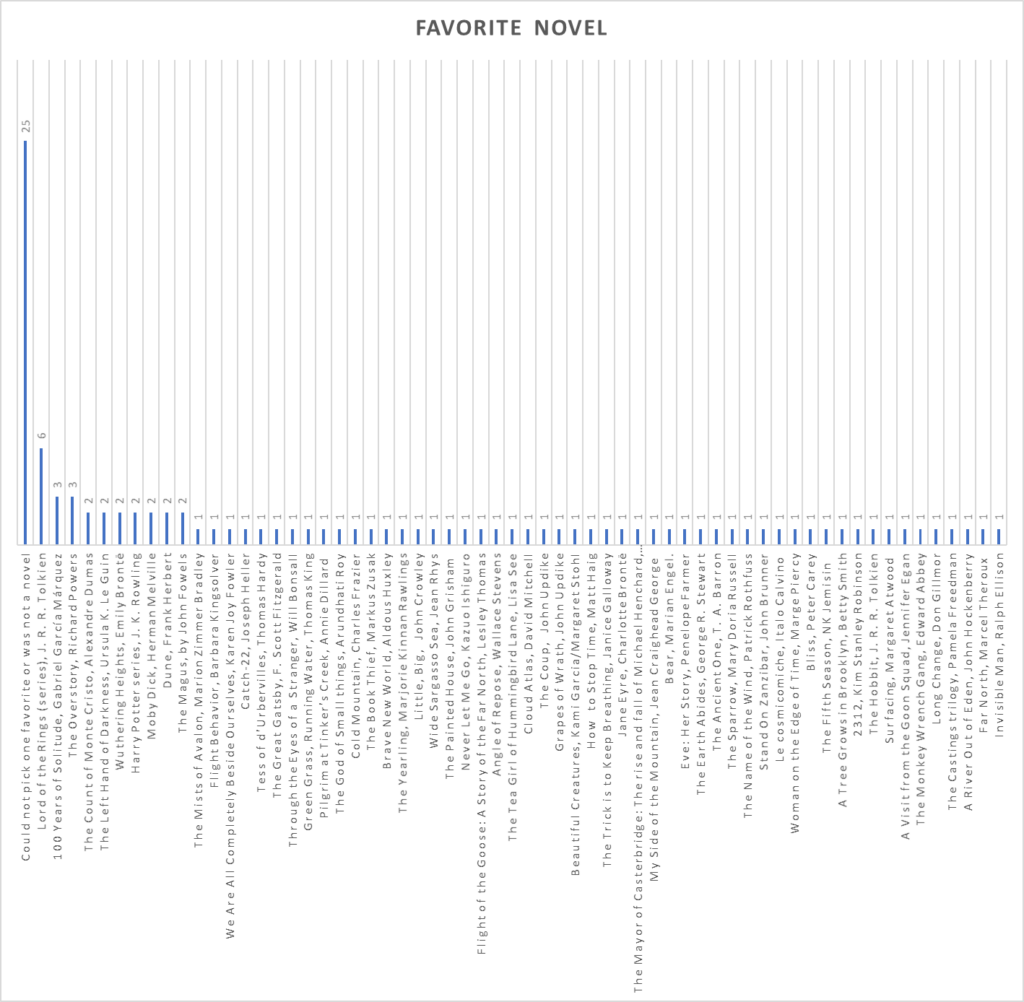

What is your favorite novel of all time, and why?

What is your favorite novel of all time, and why?

I chose this question because I wanted a sense of what readers of this survey really gravitated to when reading fiction. Of course, for a few, it was impossible to pick their favorite novel. In fact, among the 103 participants, 25 people either listed more than one novel or couldn’t pick one. The top answers were:

- Lord of the Rings series, J.R.R. Tolkien (6)

- 100 Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez (3)

- The Overstory, Richard Powers (3)

- The Count of Monte Cristo, Alexandre Dumas (2)

- The Left Hand of Darkness, Ursula K. Le Guin (2)

- Wuthering Heights, Emily Brontë (2)

- Harry Potter series, J.K. Rowling (2)

- Moby Dick, Herman Melville (2)

- Dune, Frank Herbert (2)

- The Magus, John Fowels (2)

- All the rest were singular favorites

Long-form examples:

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s 100 Years of Solitude. It was beautifully written, captured a culture with not much outside influence, was heavily part of the nature surrounding it, and was also very witty.

- Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behaviour for its subtle blending of personal and planetary catastrophe and the impact of of climate change on the natural world, and its detailed engagement with the plight of the butterflies.

- Catch-22. It was the first I couldn’t put down unless forced to, and couldn’t wait to pick back up. Absurdist. Smart. Anti-war and anti-capital-for-capital’s sake. Pro-ethics. Hilarious. Subversive. It took work but felt good doing the work. It made me sure that books had worlds to offer that the regular world didn’t, if that makes sense.

- The Book Thief (Markus Zusak) – Brilliantly written. Zusak’s use of language subtly challenged the hubris of our own human speciesism and our insistent on privileging life in general. By naming biotic and abiotic becomings as a an agential subject of a sentence, Zusak has covertly shaken many of my unconscious assumptions.

- Flight of the Goose: A Story of the Far North, by Alaskan author Lesley Thomas – this is my favorite because it ties in ecological and spiritual/animistic and cross-cultural/sociopolitical themes (these are musts, for me) all inside a powerful, engrossing human story that swept me away.

- Bear by Marian Engel. The prose is sparse and beautifully written. The topic and narrative are intriguing and thought provoking. I’ve had more great conversations about this novel with others than I have any other novel.

- The Fifth Season by NK Jemisin because it is a brilliantly crafted narrative that shows the complexity of being human and shows the consequences of not treating the earth and others with dignity and compassion.

- Long Change by Don Gillmor; I am very much interested in petroliterature and Canadian literature and I love his smooth writing, unfolding pieces of the main character bit by bit, never too predictable.

- The Magus by John Fowles. I liked the Greek Isle setting and the slow burn and kind of the thinning of that line between reality and something else.

- Stand On Zanzibar by John Brunner, one of the first eco sci fi novels to make accurate predictions about what the world would look like in the near future.

- The Left Hand of Darkness [Ursula K. Le Guin]. The worldbuilding, the multi-faceted point of views, the questions it poses, the philosophy it articulates, the environment it describes, the hardships it makes its characters endure — it’s all groundbreaking, all beautiful, and still holds up even after 50 years.

Of these novels, how many can be categorized as having environmental themes?

Since this field was not accurately given a concrete value consistently in the long-form text when answered by respondents, I manually counted 34 out of 62 (55%) selected novels that had important ecological or environmental story-building.

Genres and Topics

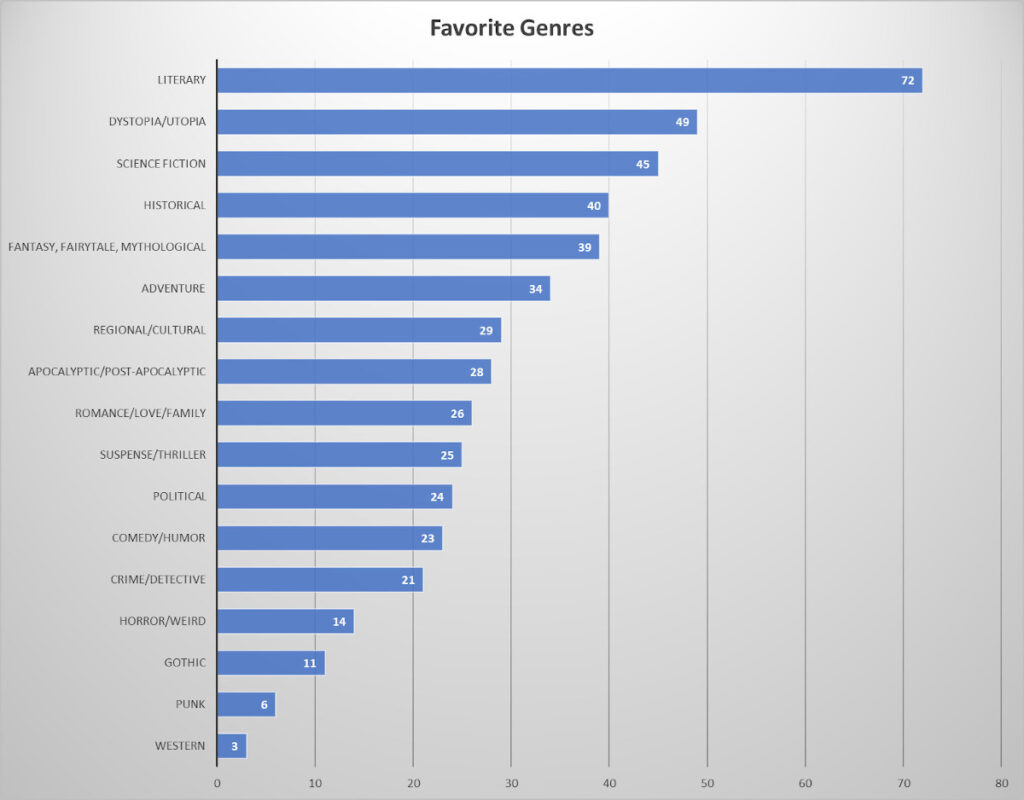

What are your favorite genres? (Check all that apply.)

The top favorite genres were literary, dystopia/utopia, science fiction, historical, and fantasy/fairytale/mythological.

The top favorite genres were literary, dystopia/utopia, science fiction, historical, and fantasy/fairytale/mythological.

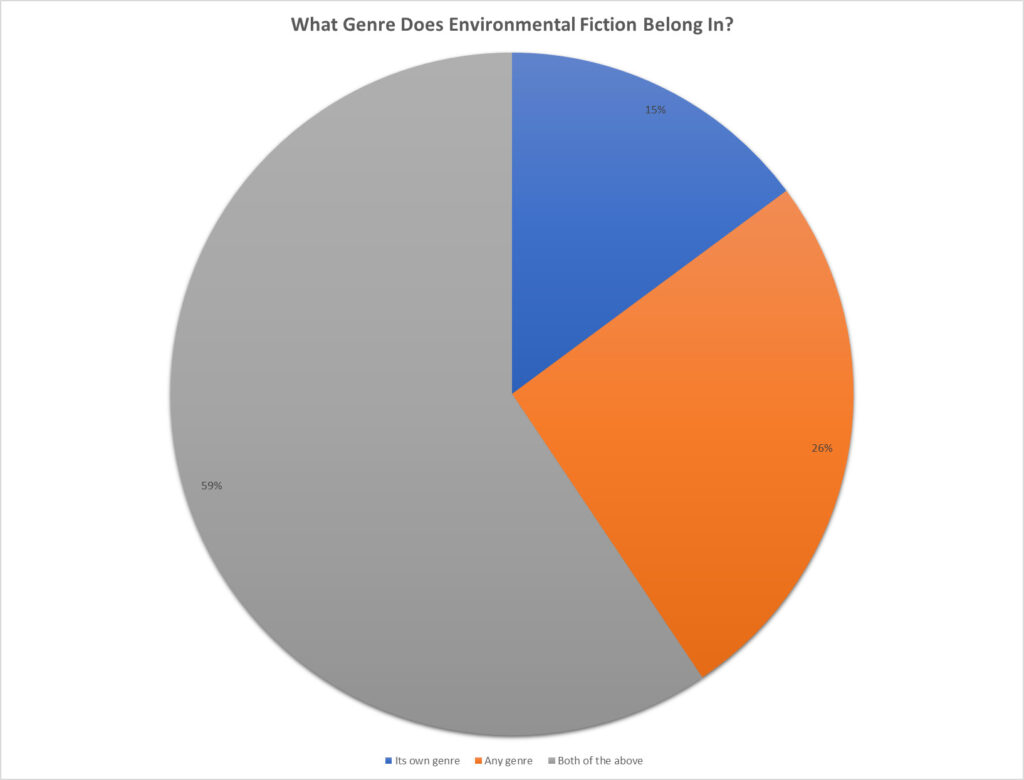

What genre does environmental fiction belong in?

When asked whether readers felt environmental fiction belonged in a genre, 15% said it belonged within its own genre, 26% said it could happen in any genre, and 59% said it could fall into both categories.

When asked whether readers felt environmental fiction belonged in a genre, 15% said it belonged within its own genre, 26% said it could happen in any genre, and 59% said it could fall into both categories.

Impact Questions

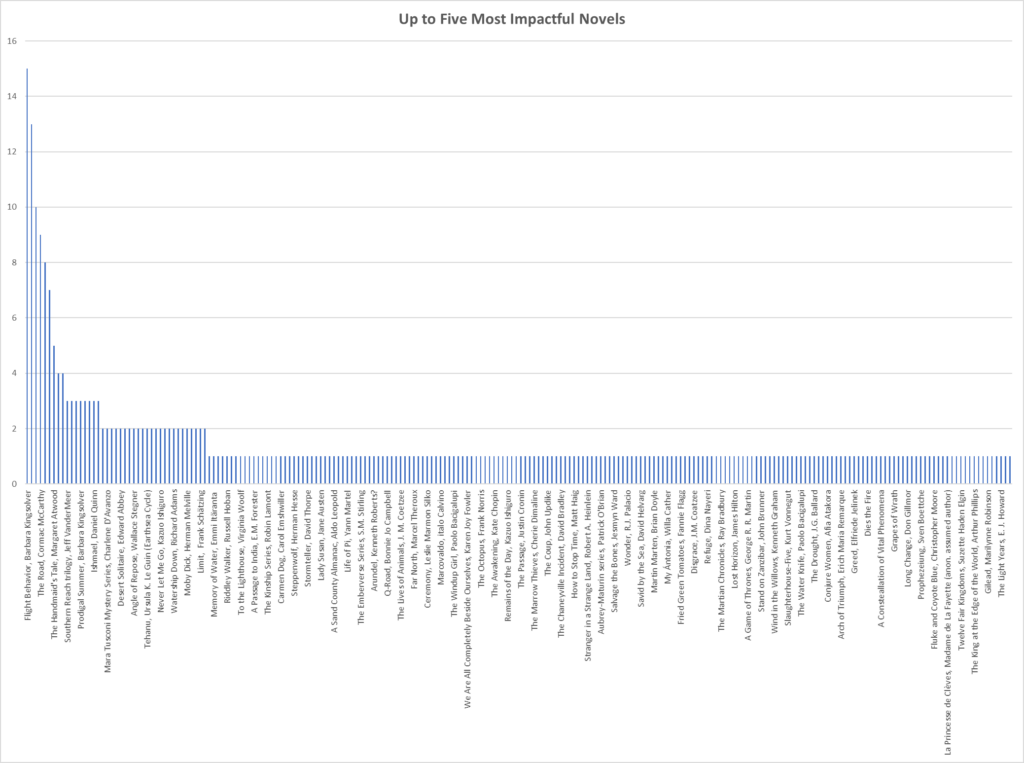

What environmental or non-environmental novels have had the most impact on you, and why? List up to five.

Personal impact question: I’ve edited the graph to show all reader answers. Readers’ top five novels are not surprising, and also interesting! Again, however, here is where I think a more diversified audience would have been key. By design, I wanted to see how “favorite novel” (asked earlier) and “up to five most impactful novels” varied. What differentiates favorite from most impactful? How does the participant react differently when being asked to choose one versus more than one? Some common reasons for why these novels were most impactful were as follows, though many participants did not give reasons. The top picks were Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior (15), Richard Power’s The Overstory (13), Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy (10), Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (9), Edward Abbey’s Monkey Wrench Gang (8), and Ursula K. Le Guin’s Hainish Cycle series (7).

Long-form examples of why novels were impactful:

- Realism or compelling account of or reflection of society, scary or not

- Goes beyond readers’ culture–expands minds

- Humorous

- Story focused on characters versus an issue

- Learned something new

- Opened readers’ minds

- Captured imagination

- Positive endings

- Good storytelling

- Interesting characters

- Suspense and/or psychological burn

Long-form examples of impactful novels:

- The Lord of the Rings: I think this may have crystallized my environmental ethics. The heroes live in forests and small agrarian communities, and the villains live in charred wastelands.

- I thought Flight Behavior was very well done because it focused on people (rather than the issue).

- Emmi Itäranta’s Memory of Water. It’s a wonderful story, but what appealed to me was the style of writing. It’s very raw and prose-like, which provoked feelings of utter beauty but also unease.

- MaddAddam series for its scary realism — was the trilogy that made me wake up and realize we MUST start writing positive future novels or we’re doomed; Flight Behavior for its realism.

- Ishmael (Quinn) – As a fairly new professor, I used this book allegorically in my undergraduate classes. It captured students’ imagination about multiple ways of seeing and being in the world.

- Prodigal Summer by Barbara Kingsolver made me want to be a writer. The Glass Bead Game by Herman Hesse made me want to pursue my PhD.

- Cormac Mccarthy’s The Road for its spare post-apocalyptic world where even language seems to run out.

- The Road (McCarthy) – This is another novel that I used in teaching graduate students about the power of climate change on human sustainability.

- The Marrow Thieves [Cherie Dimaline] was really amazing. The dystopic beginning felt so real, and then the positive ending was so good. I loved it and it made me think about how climate change can possibly have impacts beyond just our physical and mental health, but also our dreams!

- Walkaway by Cory Doctorow had a section on why we haven’t responded well to advice to combat climate change, that we had lost all wonder for nature. It was something I was thinking but couldn’t articulate. This helped me articulate it.

- The Fifth Season, A Door into Ocean, The Drought, Gardens in the Dunes, Salt–because they all offer alternate perspectives and storyworlds that navigate the realities of colonialism, slavery, capitalism, and racism in ways that create stories gripping enough for the casual reader to enjoy while still having a strong message.

- The Last Wild trilogy by Piers Torday. (This trilogy has changed my perspective regarding human animal relationship in the age of anthropocene. My anthropocentric perspective was challenged in favour or a more holistic environmental ethic.)

- Frank Herbert’s Dune – it was the first time I’d seen a literary rendering of an ecosystem that felt real. The ideas of ecology are woven into this story in a way I didn’t think was possible for fiction, before reading it. Interconnection is hard to think about, hard to grasp, and Dune showed me that fiction, done well, can really help with this.

- Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation – If Dune illustrated to me that ecosystems and species interactions could be effectively woven into a story, VanderMeer has mastered the technique. Annihilation is full of weird systems and bizarre life which seem fantastic but also exactly like the weird world around us.

- On Such a Full Sea by Chang-Rae Lee because the future it portrays seems so plausible. Also, the characters’ philosophic discussions of work resonate with me.

- Submergence. JM Ledgard’s writing is superb, the detail and place-writing. This is a perfect example of ecofiction, I think, where it’s obvious that both characters are strongly connected to water and to each other.

- Rory Power’s Wilder Girls. This book is mind-blowingly unique and utterly interconnected with the beast that is human and the connection of the wild around the human.

- 1984, one of the most astute warnings of the evils of Communism and other totalitarian ideologies.

- Blood Shot by Sara Paretsky and The Lord of the Rings. These two works of fiction create a wide and inter-related view of a living world where respect and love for nature and the immediate human environment are in constant conflict with the dangerous and destructive greed/worship of power and wealth.

- Lord of the Flies. The psychology and morality dissolve was interesting, though I read later about the 6 Tongan boys whose shipwreck experience turned out way more healthy and helpful.

- Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker is a compelling account of society, people and culture long, long after an eco catastrophe. And I’d say that Michel Faber’s Under the Skin had an impact, both in being different from the film (which inspired me to read it) and specifically in its satire on industrial farming and meat-eating.

- TC Boyle’s Friend of the Earth for its insights to the need for change.

Name a fictional character in an eco-novel who has inspired you the most. Why?

Personal impact question:

- Dellarobia, Flight Behavior by Barbara Kingsolver (7 votes)

- The gorilla from Ishmael by Daniel Quinn (4 votes)

- Crake, Oryx and Crake by Margaret Atwood (3 votes)

- Ti Tierwater, A Friend of the Earth by T. C. Boyle (2 votes)

The above list shows answers that received more than 1 vote. Of the other 63 singular votes, some novels having been mentioned earlier in the survey, such as Dune (which had two favorite characters: Liet Kynes and Paul Atreides), The Overstory (Patricia and Mini Ma), and The Lord of the Rings (Gandalf and Sam). Other favorite characters: The Fifth Season‘s Essun, Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach’s biologist, Wall-e, Richard Powers’ The Overstory‘s Plant Patty, Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower‘s Lauren Oya Olamina, Ada in Akwaeke Emezi’s Freshwater, Frankenstein, Emiko in Paolo Bacigalupi‘s The Wind up Girl as well as the author’s Nailed from Ship Breaker, Nell in Jean Hegland’s Into the Forest, and Nora in Kathleen Dean Moore’s Piano Tide. Some respondents also were impacted by animal characters such as Pooch from Carol Emshwiller’s Carmen Dog and animals from Jack London’s novels and The Octopus.

Not everyone answered the question why, but some common reasons for being affected by characters were: genuine characters with faults (ordinary but rises above it), ecological sensibility, courage, resiliency, loyalty, transformation, empowering, funny, observant, strong, survivors, wise, knowledgeable, transform/redemption, quiet dignity, and culturally diverse.

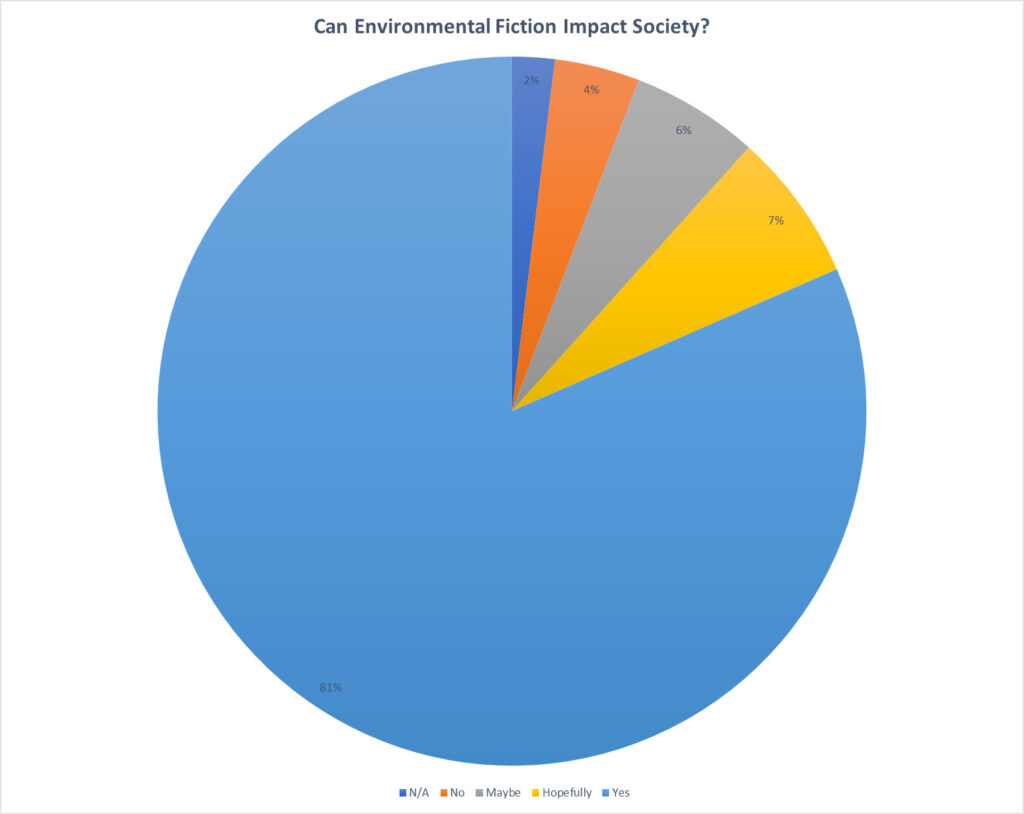

Do you think that environmental themes in fiction can impact society, and, if so, how?

Societal impact question: An overwhelming 81% said yes to this one! Few people (4%) said no, and the rest were in-between.

Examples (summarized):

- Fiction can encourage empathy and imagination. Stories can affect us more than dry facts.

- Good stories will appeal to readers’ hearts.

- Environmental themes can reorient our perspective from egocentrism to the greater-than-human world.

- Fiction is one way that helps to create a vision of our future.

- Fiction raises awareness, encourages conversations and idea-sharing.

- Fiction could impact society, but fiction today is poorly told and polemic; the author is preaching to the choir. Ham-handed approach to fiction will turn people off.

- Novels can shift viewpoints without direct confrontation, avoid cognitive dissonance, and invite reframed human-nature relationships through enjoyment and voluntary participation.

- As long as fiction is artful and not polemic.

- Good stories can impact society similar to Uncle Tom’s Cabin did.

- Stories can immerse readers into imagined worlds with environmental issues similar to ours.

- Science fiction and contemporary fiction can portray a realist viewpoint of the present and future, engaging us.

- Stories and myths define who we are; reference to Joseph Campbell.

- Fiction can trigger a sense of wonder about the natural world, and even a sense of loss and mourning.

- Stories can get conversations going.

- Fiction reaches us more deeply than academic understanding, moving us to action.

- Fiction plays on empathy in a way that data never will.

- Cautionary tales can nudge people to action and encourage alternative futures.

- Novelists spend more time “doing ecology” in novels than we realize, particularly in weird, fantastical, and mythic genres.

- Studies have already shown that good stories have positive impact, so it doesn’t seem to be any different for environmental fiction’s impact.

- An example given of Charles Dickens’ stories still being told and sold, but lessons we should have learned have still not been put into place.

- Kim Stanley Robinson’s allegorical books let us dream and give us the strength to fix things.

- Stories and songs shape society; help us to learn, adapt, and grow.

- Fiction is a way to tell scientific stories creatively, which people might want to read.

- Novels tell a story that science isn’t creative enough to, usually.

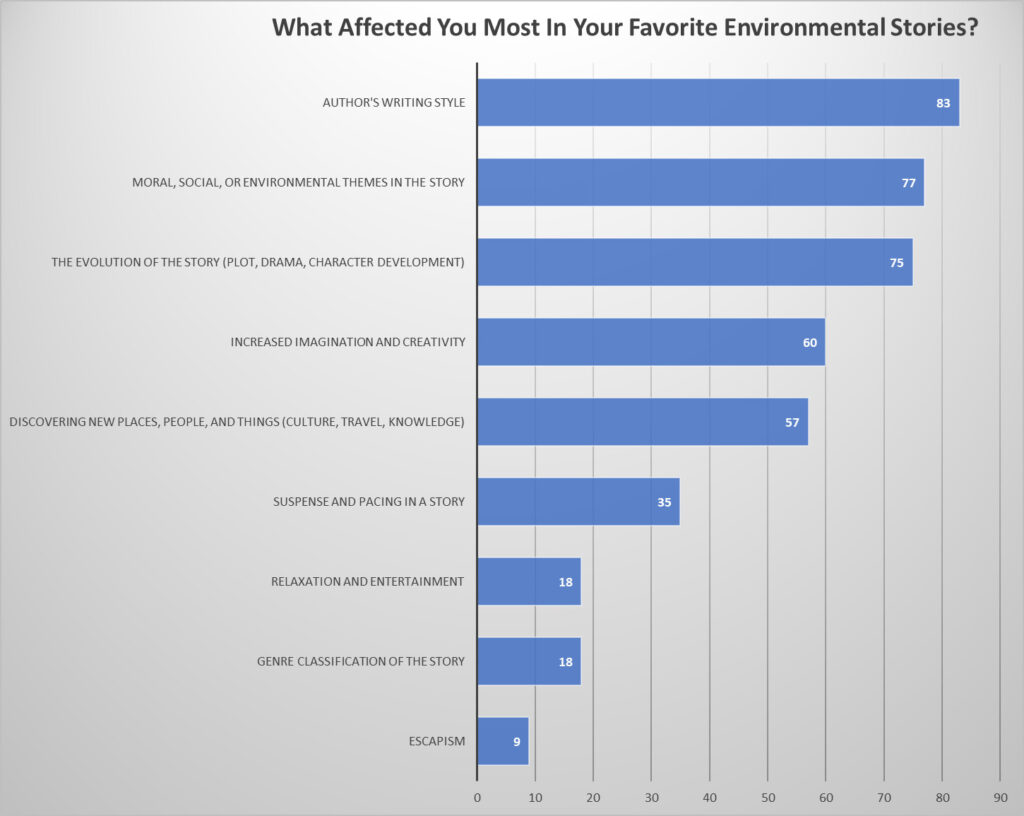

What affected you the most in your favorite environmental stories? (Check all that apply.)

Personal impact question: Compared to five most impactful novels (and long-form why) question above, this preset question about what most affected the reader from their favorite environmental novels seemed to match together:

Personal impact question: Compared to five most impactful novels (and long-form why) question above, this preset question about what most affected the reader from their favorite environmental novels seemed to match together:

- Realism or compelling account of or reflection of society, scary or not (similar to moral, social, or environmental themes in the story)

- Goes beyond readers’ culture–expands minds (similar to discovering new places, people, and things, though more represented in this graph)

- Humorous (relaxation and entertainment)

- Story focused on characters versus an issue (author’s writing style/the evolution of the story)

- Learned something new (discovering new places, people, and things)

- Opened readers’ minds (discovering new places, people, and things)

- Captured imagination (increased imagination and creativity)

- Positive endings (relaxation and entertainment)

- Good storytelling (author’s writing style)

- Interesting characters (author’s writing style)

- Suspense and/or psychological burn (suspense and pacing)

This question also had an “Other” field, where single readers added the following: verisimilitude, nature revolting, value in activism, allegory, envisioning a better future, and two others that fell into the above categories already.

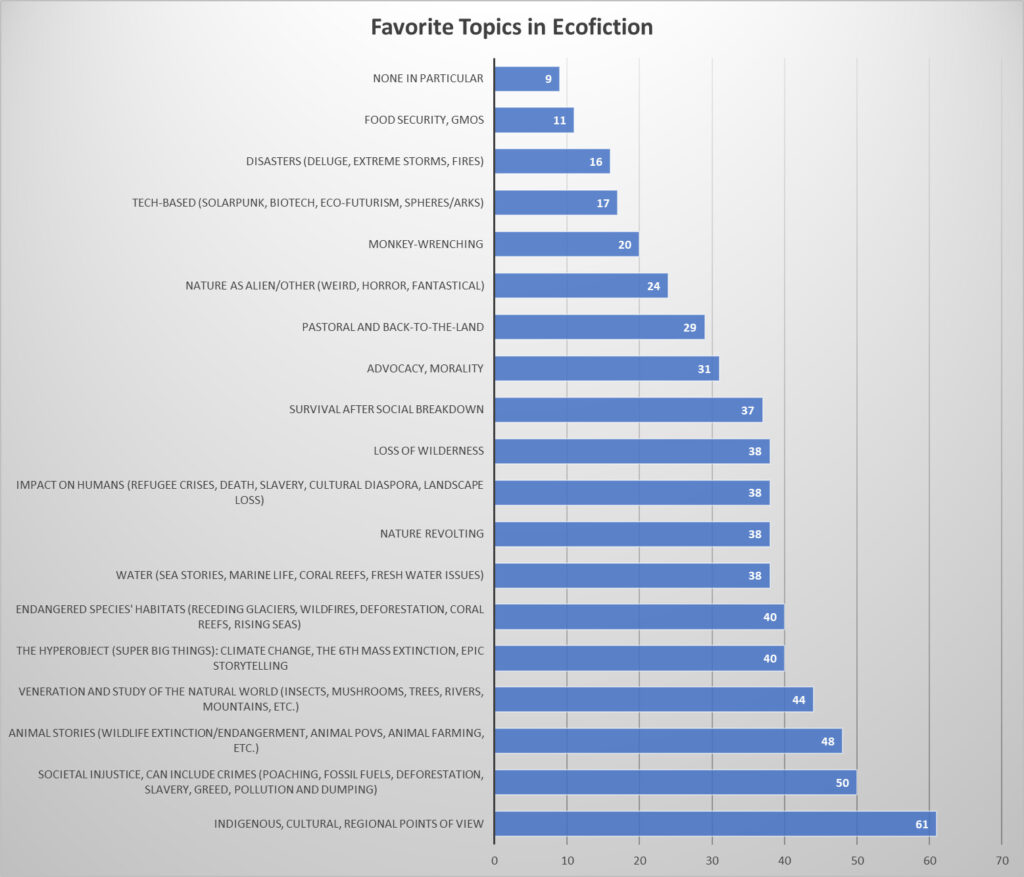

If you like environmental fiction, what topics do you look for? (These overlap, so select all that apply.) Note that these are subjects in novels around which characters and plots are driven.

Note that I chose these categories of literature based upon the database I’ve been building for going on eight years now and observations I’ve made along the way about common subjects within environmental fiction, though I wouldn’t say that these topics are necessarily exhaustive, just more common. Many of these topics overlap. When asked to choose as many relevant (but overlapping) favorite topics in eco-fiction, the number one choice was indigenous, cultural, regional points of view (61 votes), which made me happy based upon my world series that looks at different places and cultures. Social injustice, which can include crime (poaching, fossil fuels, deforestation, slavery, greed, pollution, and dumping) got 50 votes. Animal stories, which included wildlife extinction and endangerment, animal points of view, animal farming, etc., got 48 votes. Veneration and study of the natural world, including insects, mushrooms, trees, rivers, mountains, etc., got 44 votes. Next was the hyperobject, such as climate change and the 6th mass extinction, with 40 votes. Then endangered species’ habitat issues, such as receding glaciers, wildfires, deforestation, coral reefs, rising seas, got 40 votes as well. Tied at 38 votes were the topics of water (sea stories, marine life, coral reefs, fresh water issues), nature revolting, and impact on humans (refugee crises, death, slavery, cultural diaspora, landscape loss), and loss of wilderness overall. Following close behind were survival after social breakdown (37 votes), advocacy and morality (31 votes), and pastoral and back-to-the land themes at 29 votes. Then were monkey-wrenching (20 votes), tech-based–such as solarpunk, eco-futurism) at 17 votes, and disasters, such as deluges, extreme storms, and fires, at 16 votes. The least favorite topic was food security and GMOs (11 votes). Nine respondents voted for “none in particular.”

Note that I chose these categories of literature based upon the database I’ve been building for going on eight years now and observations I’ve made along the way about common subjects within environmental fiction, though I wouldn’t say that these topics are necessarily exhaustive, just more common. Many of these topics overlap. When asked to choose as many relevant (but overlapping) favorite topics in eco-fiction, the number one choice was indigenous, cultural, regional points of view (61 votes), which made me happy based upon my world series that looks at different places and cultures. Social injustice, which can include crime (poaching, fossil fuels, deforestation, slavery, greed, pollution, and dumping) got 50 votes. Animal stories, which included wildlife extinction and endangerment, animal points of view, animal farming, etc., got 48 votes. Veneration and study of the natural world, including insects, mushrooms, trees, rivers, mountains, etc., got 44 votes. Next was the hyperobject, such as climate change and the 6th mass extinction, with 40 votes. Then endangered species’ habitat issues, such as receding glaciers, wildfires, deforestation, coral reefs, rising seas, got 40 votes as well. Tied at 38 votes were the topics of water (sea stories, marine life, coral reefs, fresh water issues), nature revolting, and impact on humans (refugee crises, death, slavery, cultural diaspora, landscape loss), and loss of wilderness overall. Following close behind were survival after social breakdown (37 votes), advocacy and morality (31 votes), and pastoral and back-to-the land themes at 29 votes. Then were monkey-wrenching (20 votes), tech-based–such as solarpunk, eco-futurism) at 17 votes, and disasters, such as deluges, extreme storms, and fires, at 16 votes. The least favorite topic was food security and GMOs (11 votes). Nine respondents voted for “none in particular.”

An “Other” option included the following singular responses: vegan themes, nonfiction (this survey did not have time to go there), multi-species perspectives and post-humanism, didn’t like “far-left” mindsets, and construction of other possible worlds. Other answers from this option and a secondary follow-up question for giving more explanation fell into the already existing categories above. Note that I did not record a couple participants trying to sell me on their own projects or books (see the submission guidelines on this website).

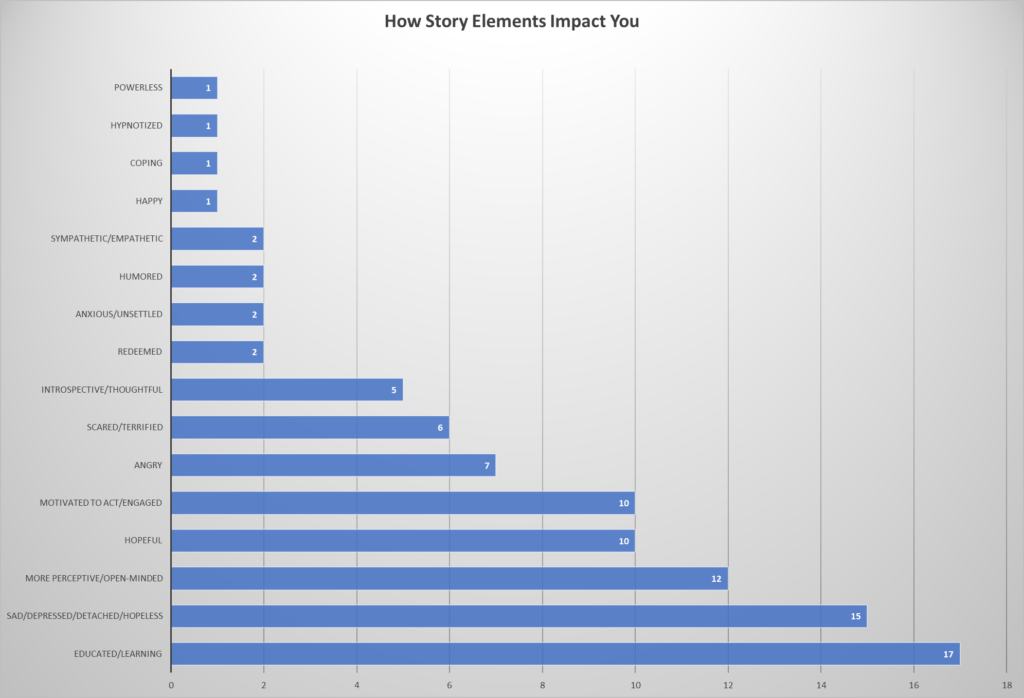

Expand on how certain story elements affect you. Did they make you angry or sad or hopeful, make you think more about the world or your own life, make you change your mind about something, or something else?

This long-form question built upon the previous question by gauging how elements of a story affected the reader. I categorized readers’ answers and ran a COUNTIF on these categorizations. This looked at how, rather than why, impacts happened. The top answers were that readers became more educated, depressed, and more open-minded from fiction that impacted them. Next, readers were also more hopeful, motivated to act/engaged. From there, the less common answers were: angry, scared, redeemed, anxious, humored, more empathetic, and happy.

This long-form question built upon the previous question by gauging how elements of a story affected the reader. I categorized readers’ answers and ran a COUNTIF on these categorizations. This looked at how, rather than why, impacts happened. The top answers were that readers became more educated, depressed, and more open-minded from fiction that impacted them. Next, readers were also more hopeful, motivated to act/engaged. From there, the less common answers were: angry, scared, redeemed, anxious, humored, more empathetic, and happy.

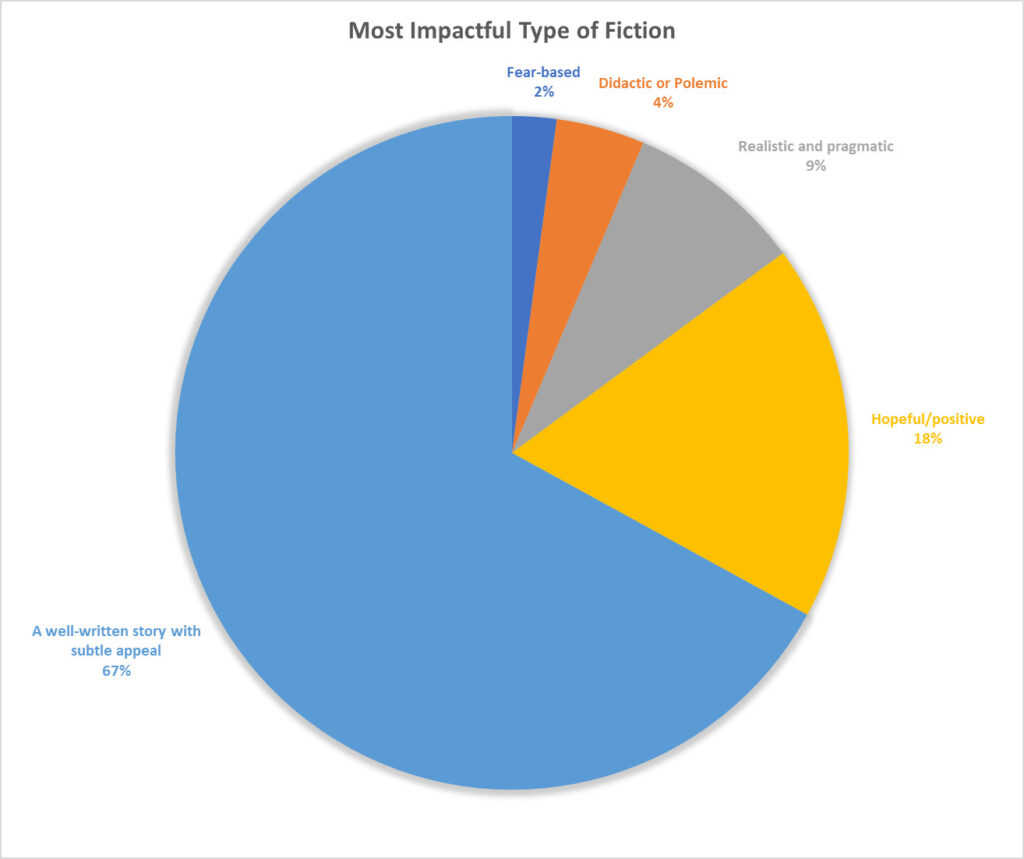

What do you think is the most impactful type of fiction?

Personal impact question: These answers did not surprise me at all. Let this be of note to writers wondering how to approach their stories. These categories go beyond normal taxonomies and are based on story appeals rather than specific genres and topics. See below for more detail.

Personal impact question: These answers did not surprise me at all. Let this be of note to writers wondering how to approach their stories. These categories go beyond normal taxonomies and are based on story appeals rather than specific genres and topics. See below for more detail.

What turns you off in fiction that has moral imperatives?

Personal impact question: There is no graph for this due to the long-form question type. The most common answers (some overlap ideas) were:

- Religious or political agenda

- Being hit over the head and not being able to make my own choice

- Overly simplistic or cliche

- Guilt-tripping

- Preachiness

- Bad writing

- Judgmental

- Focus on problems but not on solutions

- Not subtle

- Pandering to people already in their base

- Overly technical writing

- Lack of diversity among characters

- Instructional/polemic

- Only about humans’ loss

- Too much narration

- Fear-mongering

- Fatalism

- Self-righteousness

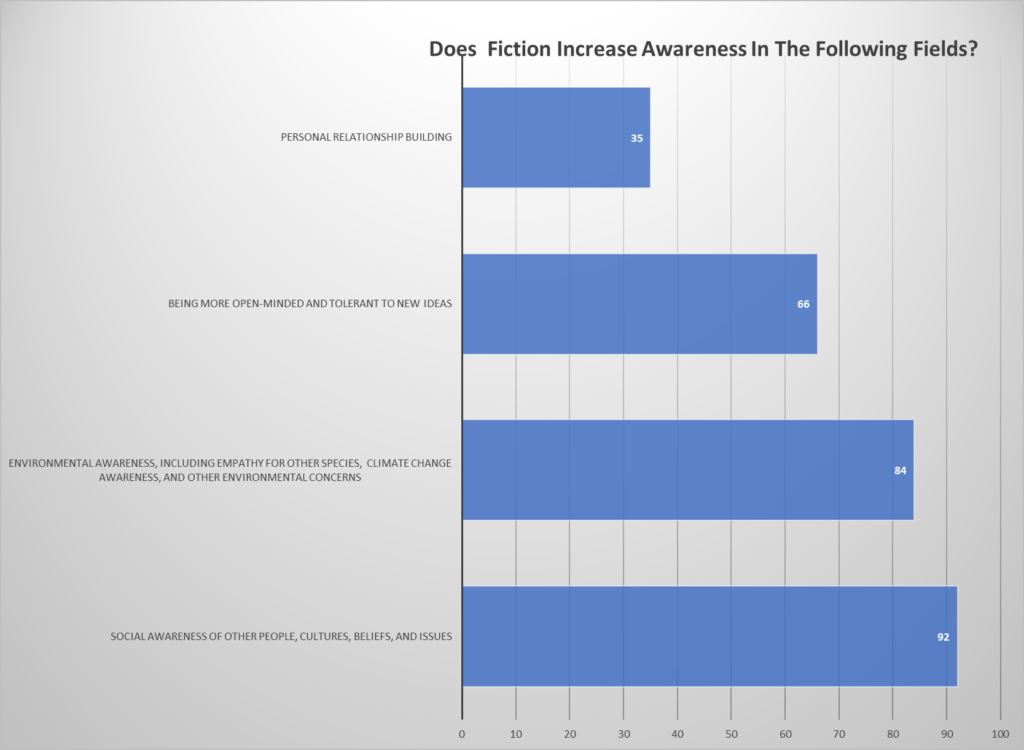

Do you feel that reading fiction has increased your awareness in any of the following fields? (Check all that apply.)

This question looks at the types of awareness increased from reading environmental fiction. Social awareness of other people, cultures, beliefs, and issues seems to be a trend, along with participants wanting more diversity in characters (from the previous question). Also, this favorite choice lines up with the most liked topic: indigenous, cultural, regional points of view. Environmental awareness, including empathy, is not surprising as a strong pick either. Many studies have already shown that when readers get emotionally attached to a story, empathy increases (though more respondents chose empathy in the predetermined questions rather than from the previous long-form question about how story elements affected them). Two articles reference these studies from my writer’s workshop slideshow. See BigThink’s article and sound clip Why Reading Fiction Is as Important Now as Ever and Psychology Today’s The Real-Life Benefits of Reading Fiction. Being more open-minded and tolerant to new ideas might overlap with the social awareness answer, but I added it separately to distinguish it from specifically culture-based ideas–though looking back, I think I could have worded this field differently.

This question looks at the types of awareness increased from reading environmental fiction. Social awareness of other people, cultures, beliefs, and issues seems to be a trend, along with participants wanting more diversity in characters (from the previous question). Also, this favorite choice lines up with the most liked topic: indigenous, cultural, regional points of view. Environmental awareness, including empathy, is not surprising as a strong pick either. Many studies have already shown that when readers get emotionally attached to a story, empathy increases (though more respondents chose empathy in the predetermined questions rather than from the previous long-form question about how story elements affected them). Two articles reference these studies from my writer’s workshop slideshow. See BigThink’s article and sound clip Why Reading Fiction Is as Important Now as Ever and Psychology Today’s The Real-Life Benefits of Reading Fiction. Being more open-minded and tolerant to new ideas might overlap with the social awareness answer, but I added it separately to distinguish it from specifically culture-based ideas–though looking back, I think I could have worded this field differently.

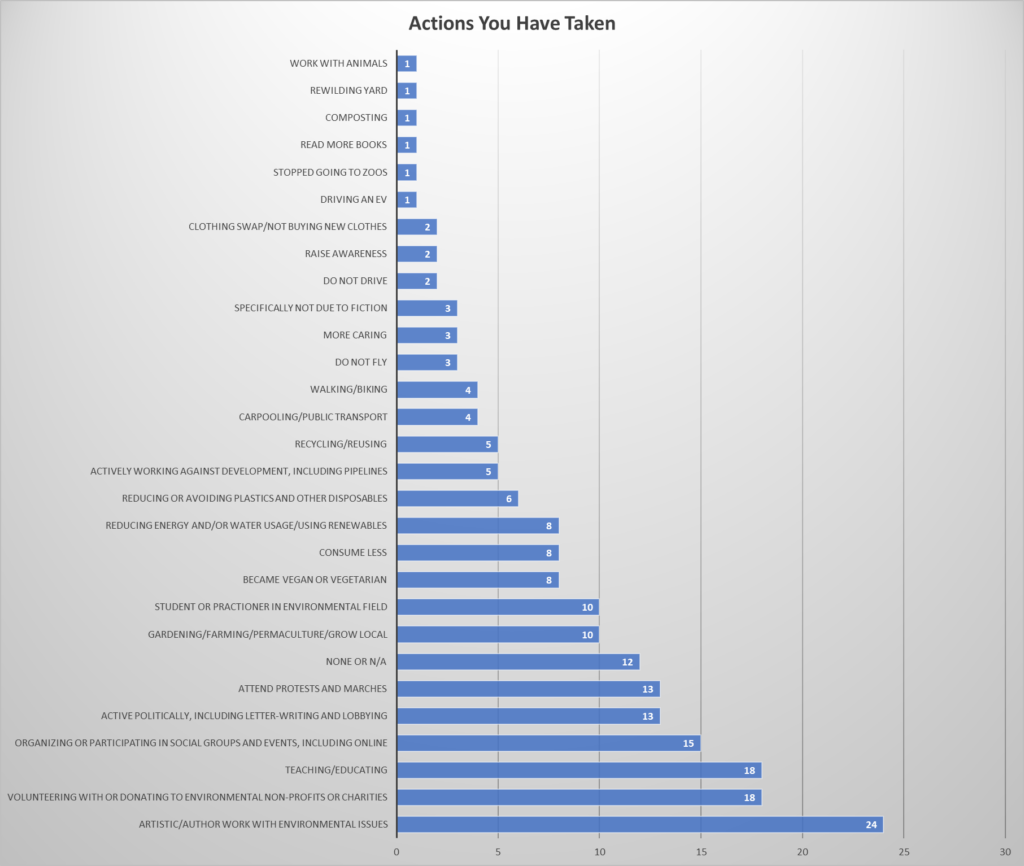

Feelings are one thing, but activism is another. Did you change your life based upon a novel that affected you? Which novel was it? What do you feel moved you to take action?

Personal impact question: The answer was in long-form, so I summarized the answers into the above categories. Respondents often listed more than one action. Three respondents said that that their activism was not due to reading novels; participants didn’t answer the question about which novel inspired them.

Personal impact question: The answer was in long-form, so I summarized the answers into the above categories. Respondents often listed more than one action. Three respondents said that that their activism was not due to reading novels; participants didn’t answer the question about which novel inspired them.

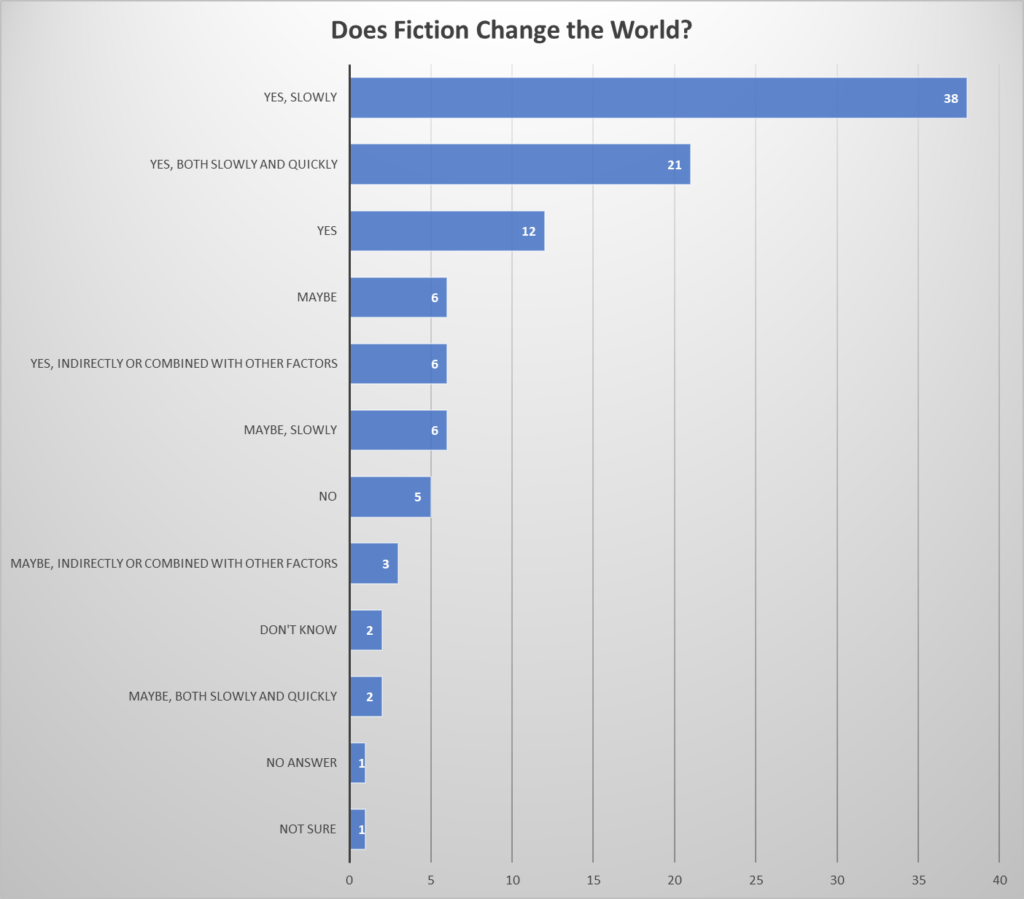

In your opinion, do fictional stories change the world? Do you think this change happens slowly, over time, or largely at once? Give examples.

Societal impact question: There’s a majority yes to this question, but respondents broke that down into it happening slowly, quickly, both (as in slowly and then quickly), or in combination with other factors.

Societal impact question: There’s a majority yes to this question, but respondents broke that down into it happening slowly, quickly, both (as in slowly and then quickly), or in combination with other factors.

Long-form examples:

- It’s hard to quantity. Does a bestselling novel change attitudes, or does it reflect attitudes that were already changing due to other factors, or both?

- Yes, I believe fiction changes the world. Unfortunately, it happens slowly. An example would be Stephen Crane writing about NY squalor at the turn of the century, causing folks to become aware.

- I think fiction, especially speculative fiction, can lay the groundwork for change by simply articulating different possibilities. It’s the planting of many seeds that captures our imagination and thus our creations. I’m very interested in how solarpunk and Afrofuturism can alter the shape and discourse of how we envision the future.

- Fiction does change the world but it is a slow and lengthy process. To give one example, I believe without Brave New World we would be ill prepared to deal with the speedy developments in cloning and human genetic manipulation. At a philosophical level that book must have helped the design of laws and rules pertaining to bioethics and cloning.

- Probably. At least I hope so. I am currently doing my Masters research project on how speculative fiction can be a tool utilized by social movements to envision alternative futures, which hopefully lead to societal transformation. I would say that the change happens over time, especially when considering that you often have to change peoples’ mind.

- I think certain fictional stories can definitely change the world, and we have examples of them changing the course of history. The publication of ‘Black Beauty’ caused a sensation in Victorian society and permanently changed the way many people thought about their horses, and sparked interest in the new RSPCA charity. And in terms of social issues, things like A Christmas Carol had a huge effect on raising awareness of poverty and the important of considering others at Christmas – it is said Christmas was becoming unfashionable and was barely celebrated in some quarters, but this book revived the idea with a new imperative to be charitable. ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ has also changed the world in terms of women’s rights, it’s strengthened feminist activists in their resolution to fight. Some books don’t have much effect, of course, but some really do.

- I think change happens both slowly and largely at once. However, when we reach tipping points, change happens fast. Unfortunately, it seems like we have to experience The Tragedy of the Commons over and over, i.e., reaching tripping points, and being forced to react instead of being proactive to preserve The Commons.

- I do believe fictional stories change the world, but these changes happen slowly rather than quickly and that the effects of individual books are cumulative. Dickens was critical about child labour, Zola’s ‘Germinal’ underlined the difficult working conditions of coal miners. Their novels did not eradicate these issues, but they framed them in a new way, which in turn opened some eyes and changed some minds.

- Sometimes. The most obvious example I can think of is a negative one. When people read fiction as fact, we run into problems. Michael Crichton’s State of Fear did a HUGE amount of damage to public understanding of climate change. It was a complete misrepresentation of the science, and because people read it as fact it influenced the way they think–he was even invited to testify in Congress as an expert, though he was just a novelist.

Anything to Add?

The final question was long-form, and most people said no or thank you (and thank you!). Here are some other examples, some of which I would like to reply to:

- I think there is some responsibility not to paint self-fulfilling, disempowering dystopic futures or preach about environmentalism to the converted, but to dare to imagine inspiring and realistic future visions, as settings for potentially popular fictional narratives, that demonstrate how humanity might successfully meet climate change’s challenges and make a better world/solve multiple challenges. Not a tall order, is it? Creators have the power to empower and give hope.

- Great survey! How can I get the results? [I will be emailing all the people/organizations I shared this survey with when the survey results are ready. ]

- I love this brilliant and unprecedented concept called dragonfly.eco. I want in, and believe that I have found a well-meaning and lively vent for my eco-themed writings. [Thank you, and to contribute, please see all the submission guidelines for this various areas of the site!]

- I realise you were probably looking for informants without my specific background, but I think the project sounds interesting and hope to read more about it in the future. Good luck! [Thanks, and I’m looking for all backgrounds, so I appreciate your interest and time in completing this survey.]

- I think there needs to be equal attention given to ecoessays. [This site focuses on the novel, but all types of resources are important.]

- I would warn against trying to pin a direct cause and effect between reading environmental themes and affecting environmental behaviour. Human beings are complicated and contradictory creatures. I think the best we can hope for is that fiction can increase (or at least enhance) the breadth of our spheres of consideration and/or the depth of our empathy towards the other. Plus to open our eyes to new alternatives and ways of living. [Thanks, and I agree.]

- If possible, I’d love to help out in your research. Or even just talk a bit about this type of research. [Personal details removed. I have added an “Invitation” section above. I would love to help in similar research.]

- I’m looking for an agent for my eco-fiction novel. [I do not work directly with agents. I would research this separately in Google.]

- Keep up your excellent work. Also, would you like to contribute to my solarpunk magazine project? [Sure, just email me!]

- Thanks for the chance to participate, Mary. Perhaps your survey would have even more impact if you included the enormous influence of creative nonfiction writers (Muir, Leopold, Craig Childs, are just a few that come to mind). Yes, I know a survey needs parameters, but I think we have to find a way of narrowing the line between enviro fiction and nonfiction for greater impact on the world out there. [Thanks to you too! I agree that creative nonfiction is really important, but this survey follows the parameters of the site itself in focusing on fiction rather than nonfiction. At one point, I did want to try to expand it to nonfiction, but that’s such a huge undertaking and I do this completely voluntarily, so there’s just not enough time in the day. You can check out our Facebook page that sometimes explores more than just fiction. I’d also highly recommend the wonderful groups Artists & Climate Change, Dark Mountain Project, and ClimateCultures.net for more resources.]

- This area has a lot of potential, but it seems constantly squandered by authors that have no sense of the motivation or thinking behind individuals who do not already think exactly like them. That way lies a failure to persuade and a failure to have positive impact. [I somewhat agree but also tend to look more positively at the great number of equally wonderful novelists who are mashing up genres, uniquely approaching the complexity of our natural world and us humans in it, and blazing new literary trails along the way–rather than preaching to the choir or producing clichéd works: look at authors such as Jeff VanderMeer, Helon Habila, Wu Ming-Yi, Pitchaya Sudbanthad, and many others. You’ll find a lot of these folks in my interview section.]

- You research is very inclusive and has covered all the areas regarding ecofiction that i can think of. I wish you good luck with your work. Really appreciate what you are doing. [Thanks, and a million more thanks to people who responded with a “thank you” in this section. Thanks for recognizing the importance of this work and thinking this survey was interesting.]

Trends and Conclusions

The sample size (103) seems to be a good one for people who are mostly familiar with the idea of eco-fiction (and similar environmental/nature fiction genres and subgenres), though I was still hoping to get a larger, more diverse group of participants. The majority of respondents were highly educated middle-aged women. The majority of the group read from 1-29 novels a year. Favorite novels represented mostly North American or European authors (male and female about equally, with J.R.R. Tolkien, Barbara Kingsolver and Margaret Atwood consistently a favorite), with the majority of readers enjoying literary fiction the most, followed by dystopia/utopia and then science fiction. Note that the genres of science fiction and fantasy were well represented in this survey, both as favorite and most impactful novels, despite literary fiction being the favorite genre among the participants. The survey touched upon genre classifications, and the majority of participants did not seem to care either way about whether environmental novels should be classified in their own genre or not, and genre classification was near the bottom of the list when describing what affected people the most when reading their favorite environmental stories. Of novels that respondents enjoyed, readers were most impacted by good storytelling rather than preaching.

When looking specifically at types of impacts resulting from reading environmental fiction, readers liked to discover more through fiction about indigenous and other cultural points of view, preferred well-told stories over polemic or didactic fiction, thought that social and environmental awareness was increased by reading fiction, and liked hopeful stories. Favorite topics, besides new cultural ideas, included social injustice, animal stories, veneration of the wild, hyperobjects (such as climate change and extinction), and endangered habitats. Readers also felt inspired by environmental fiction for a variety of reasons, including that creative stories are easier to digest than dry scientific facts and jargon, fiction can increase empathy, good stories will appeal to readers’ hearts, science fiction can help us imagine better futures, reading impacts us like all experiences do, well-written heroes engage us and/or become our role models, and cautionary tales can move us to action. When looking at how readers were impacted, both positive and negative reactions appeared: most chose becoming more educated as a result of a story, but secondarily they also felt more depressed or hopeless. I think this is an interesting juxtaposition but is not all that surprising, as the more we learn about the world’s environmental state, the more hopeless we might feel.

One of the clearest results of this survey is that readers are not fond of agenda-based fiction that hits readers over the head with self-righteous preaching. Fiction is a form of art, and we’ve already established that readers in this survey are most affected by a well-told story with subtle appeal (if there is any appeal at all). In that sense, this survey should be helpful to writers who are brimming with concern about the natural world and our place in it but who also want to write a fictional story that reflects that concern. Most participants of this survey did not like lazy tropes, judgment, religious or political agendas, or heavy-handed storytelling. While 77 participants wanted to see moral, social, or environmental themes in a story, and 31 respondents liked advocacy and morality in fiction, only 4% of readers chose didactic or polemic methodologies of storytelling as their preferred most impactful type of fiction–and in the question about what turns readers off in fiction that has moral imperatives, the vast majority of the respondents did not want to be preached at and were concerned with clichéd tropes in fiction. A few readers throughout the survey reported that environmental fiction might have too much pandering to a particular base. Readers were also turned off by scientific denialism (such as the climate junk science presented in Michael Crichton’s State of Fear) and fiction with not enough diversity in characters and belief systems.

After some lead-up questions about how fiction increased awareness and what sorts of fiction and characters inspired readers, I asked how such impacts resulted in personal activism. 12 out of 103, or 11.7%, either said that they had not changed their lives or simply put N/A in the answer field. The remainder (88.3%) of the respondents had done something differently in their lives, with the most common being through the use of art (including becoming an author) as a vehicle to work with environmental issues. Most respondents also actively changed their lives in other ways, including how they commute, consume, work, use energy, work or teach, grow or procure food, eat, and become politically more active.

Then I asked: can fiction change the world? It’s not a buzz phrase I particularly like in news titles, but it’s one I asked in the survey because I wanted to see what readers thought about societal impact. I asked readers how they thought this change could happen: quickly, over-time, or not at all. 77 (75%) said yes, fiction can change the world, though over half of those thought it happened slowly, with a few thinking it happened indirectly or combined with other factors. 5 said that fiction cannot change the world, and the rest thought it might be able to or weren’t sure.

From this sample, it seems clear that environmental themes in fiction can impact readers, in the very least by evoking certain emotions and, in the most, by engaging readers to take actions in their personal lives. These impacts are generally positive but can be negative when readers feel preached at, told how to behave, or judged by the author or narrative. The majority of readers thought that environmental fiction, like any fiction, could change the world, at least over-time and sometimes along with other factors. The majority of readers were inspired by stories enough that they had taken personal actions in their lives–and these individual actions did not seem to exist in a bubble, since they included art, storytelling, teaching, studying in the sciences, law, voting, latching on to renewable energy, consuming less, and protesting/marching. These actions involve engagement with others, and include conversations and education, along with practical solutions for working against ecological collapse. When these types of actions are taken by more and more members in society, changes begin to ripple through society. However, this survey, though trying to examine the complexities of being human and exploring ways in which readers are changed by eco-fiction, cannot conclude with scientific evidence about how large that change is. I think it would take a larger audience and analyzing data over time to produce a historical timeline of actual changes rather than perceived ones. Yet, I feel that the survey does accurately relay individuals’ reports of ways that they were influenced by reading environmental fiction, from how they were positively or negatively impacted and what actions they took as a result of reading.

Excellent survey. Enlightening and revealing. As a writer of eco-fiction, I appreciated the thoughtful questions and detailed answers by readers that you shared here.

Excellent survey. As a middle grade ecofiction writer, I would think it impossible to get feedback on this topic with any great depth from kids, but I imagine the same psychological effects and reading preferences probably apply without them knowing. It would be nice to think that in twenty years, some of them might look back and realise that they changed their lives in some way to benefit the environment as a result of reading on of my stories. Even if it happens very slowly. I remember reading The Chrysalids thirty years after reading it at school, and I was gobsmacked by how much of its message had been impregnated in my brain without me knowing. I felt as though John Wyndham knew he was doing that, and it inspired me to use the same power if I could.

Thanks for your comments, Ian. I can look back on my life and see how I was really affected by reading stories that strongly reflected the natural world. Even though that might seem anecdotal, authors who I interview document the same thing.

Hi Mary, this is really interesting reading, thank you. As a student of ecocriticsm, I wonder if a possible ‘turn off’ for those readers not that familiar with environmental writing is the use of ‘ecolanguage’ in some texts, by which I mean, references to species, plants, geographical structures. I’m currently looking at the benefits a hypertext might bring to environmental writing by providing links to explanations and/or multimedia to help readers visualise and otherwise experience the natural world more easily through narrative. Have you encountered any feedback on this point in your surveys?

This is interesting, and I think that when it comes to fiction, a lot of readers need an info diet and want to focus on stories instead. Personally, I like knowing details, but they can bog a story down. I think e-readers have built-in links that bring up definitions these days, but hypertext glossaries might be a good idea. The only downside I can think of would be that underlined or color-highlighted links could distract readers from the story, in which case a glossary at the end (which either isn’t linked to or has more of a passive link, i.e. no link decor) would be great.