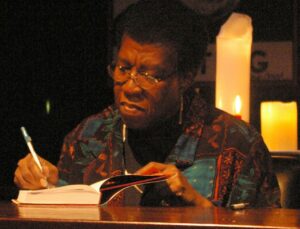

Octavia Butler, an African American science fiction writer, was born in 1947 and died in 2006. A Hugo and Nebula award winner, she wrote fairy tales as a young girl. By the time she was a pre-teen she got her first typewriter, ignoring her Aunt Hazel telling her, “Negroes can’t be writers.” (Source: Butler, Octavia Estelle. “Positive Obsession.” Bloodchild and Other Stories. New York, Seven Stories, 2005. 123-126.) Octavia’s series include the Patternist, Xenogenesis, and Parable (also called the Earthseed). In addition, she wrote two stand-alone novels, two short story collections, and several essays and speeches.

It is the Earthseed series on which this spotlight focuses, but her other works are relevant and recommended. Earthseed contains two novels: Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents. A third in the series, Parable of the Trickster, was not completed before her death. Sower opens in 2024, which once seemed so futuristic, even in the year 1993 when the book was published. But time marches impossibly on, and for those of us who clearly remember 1993, the vacuum that has sucked out space from then to now seems both eternal and too quick. If you look at a timeline of climate change (American Institute of Physics), you’ll see that global warming had, by in large, become agreed upon by scientific opinion by 1977. And by the early 1990s the first IPCC report stated that warming was likely.

Talking about the Earthseed series as very “real” tale should not drown out the story itself. Octavia helped usher in the genre of YA dystopian fiction. She wrote powerfully, imaginatively, and creatively. The worlds she built were beautiful, harsh, and grim. Her protagonists were stoic and inspiring. Despite tackling multiple issues–politics, environment, segregation, religion, social injustices, her prose was concise. Her stories, powerful and believable.

The number of authors tackling the subject of climate change in fiction has risen in the past few years, but as stated earlier in this series, many authors were writing about it before it became more mainstream. The reasoning may be that today climate change is more accepted and obvious around the world. And, of course, writers naturally take on what they see around them. But we should never forget adventurous authors like Octavia Butler who were innovative for their time. She went against the odds on many levels: gender, skin color, and story subjects. And she blew us all away.

Though a few terms have been introduced to describe the subject of climate change as a genre in fiction, one phrase that is often ignored is Afrofuturism, which, according to Inverse (“Octavia E. Butler: Why the Author Is Called the Mother of Afrofuturism,” by Kat Tenbarge, June 22, 2018), is a type of cultural aesthetic that explores the intersection of African culture with technology and futurism. Inverse calls Octavia Butler the “Mother of Afrofuturism” and describes four themes used in her books: critique of modern-day hierarchies, violence, survival, and diversity. The Earthseed series seems to accurately envision the near-future world’s downfalls, brought on by climate change and economic disparity, which have resulted in growing populism and demagoguery around the world.In African Arguments (“This is Afrofuturism, March 6, 2018), Bolanle Austen Peters states:

The term Afrofuturism, coined in 1993, seeks to reclaim black identity through art, culture, and political resistance. It is an intersectional lens through which to view possible futures or alternate realities, though it is rooted in chronological fluidity. That’s to say it is as much a reflection of the past as a projection of a brighter future in which black and African culture does not hide in the margins of the white mainstream.

Note that climate change is a historical, present, and future concern. Perhaps this future is something Octavia could envision as a child in a world where a critical dystopia didn’t seem that unimaginable, existed in some form already, and had signs of continuing, though it is reasonable to suggest that in her novels, Octavia created hopeful heroes. Perhaps she imagined herself as one such type of protagonist, and rightly so. Octavia spent her childhood in Pasadena. Her mother worked as a maid and her father a shoe-shiner. According to the New Yorker (Octavia Butler’s Prescient Vision of a Zealot Elected to ‘Make America Great Again,’ by Abby Aguirre, July 26, 2017):

In one of Butler’s first stories, “Flash—Silver Star,” which she wrote at the age of eleven, a young girl is picked up by a U.F.O. from Mars and taken on a tour of the solar system. Butler ignored the received idea that black people belonged in science fiction only if their blackness was crucial to the plot…She later made a habit of explaining, as here to the Times, “I wrote myself in, since I’m me and I’m here and I’m writing. I can write my own stories and I can write myself in.”

In Parable of the Sower are signs of climate change, such as drought and rising seas. The main character, who tells her story through journal entries, is a 15-year-old black girl named Lauren Oya Olamina, who, as the New Yorker points out, is wise enough to determine that people have changed the climate of the world. The title of the series, “Earthseed,” comes from a Darwinian religion that Lauren makes up. She also has hyperempathy, which makes her keenly attuned to the pain that her fellow residents in southern California experience in their impoverished life behind a wall of segregation made of brick and steel. Issues of skin color, violence against those perceived as different, political movements against science, and class divisions growing wide sound all too familiar. In Parable of the Talents, which opens in 2032, further oppression of women, designer drugs that let people numb out, mutilation of body parts, and slavery are common. Cities are privatized, and literacy is decreasing. The Earthseed series tells of what we have, are, and will continue to experience. Electric Lit points out: As Gloria Steinem wrote in 2016, in an essay celebrating The Parable of the Sower‘s 25th anniversary, “If there is one thing scarier than a dystopian novel about the future, it’s one written in the past that has already begun to come true.”

Indeed, the current political climate in the United States reflects some of what’s going on in this novel, including news briefs (think Twitter), where a bulleted note about war and a comment about Christmas lights might carry the same weight in 25 words or less, but most frightening is:

The Donner Administration has written off science, but a more immediate threat lurks: a violent movement is being whipped up by a new Presidential candidate, Andrew Steele Jarret, a Texas senator and religious zealot who is running on a platform to “make American great again.” –The New Yorker, ibid

According to Wired Magazine (Sci-Fi Tried to Warn Us About Leaders Who Want to “Make America Great Again,” by the University of Illinois Press, December 6, 2016), Gerry Canavan, who wrote the biography Octavia E. Butler: An Outsider’s Journey to Literary Acclaim, said that the presidential character was actually inspired by Ronald Reagan, but it reeks of the current president as well–two decades after Talents was published–who uses the exact phrasing of “make America great again.” Maybe what Octavia was concerned about was that we need to make it great someday, but we cannot make anything great by disregarding scientific fact, civil rights, ecological and economical sustainability, forethought, and equality.

Climate change doesn’t really fit in to either reality or fiction in a compartmental sense. It looms over society and is a result of many other root issues, such as greed and capitalism. Octavia Butler recognized this and world-built her stories by looking at what wasn’t, isn’t, or won’t be “great.” Her novels lie on the path of “If we continue this…then.” If society sees a natural resource it can make money off of, capitalism provides a path for that. Eventually, with too many resources taken, not only is the climate itself altered but the same kind of root greed doesn’t disappear, such as in Parable of the Sower, where water is scarce and thus is finally controlled by the government–and is not as available for those behind the wall.

The epilogue sees a very aged [Lauren] Olamina, now world-famous, witnessing the launch of the first Earthseed ship carrying interstellar colonists off the planet as she’d dreamed. Only the name of the spaceship gives us pause: against Olamina’s wishes the ship has been named the Christopher Columbus, suggesting that perhaps the Earthseeders aren’t escaping the nightmare of history at all, but bringing it with them instead.

I leave you with this quote, from Parable of the Talents, by Octavia E. Butler:

Choose your leaders with wisdom and forethought.

To be led by a coward is to be controlled by all that the coward fears.

To be led by a fool is to be led by the opportunists who control the fool.

To be led by a thief is to offer up your most precious treasures to be stolen.

To be led by a liar is to ask to be told lies.

To be led by a tyrant is to sell yourself and those you love into slavery.