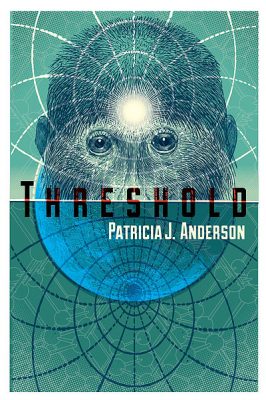

I had the pleasure of talking with Patricia J. Anderson, author of Threshold, recently published by Common Deer Press. This month’s interview comes from the perspective and lives of other species, providing a fresh outlook in the field of eco-fiction. Thanks to Patricia and Common Deer Press for the opportunity to discuss this novel.

Book summary: The population of Ooolandia (a world much like our own but with an extra “O”) is hypnotized by the culture of MORE – MORE thrills, MORE things, MORE big bottles of beer. Citizens of all kinds and colors go about their lives unaware that hidden in the fog of everydayness a great calamity is approaching. Banshooo, an especially clever primate, works for the Ooolandian Department of Nature where he has amassed data proving, beyond any doubt, that the natural world is losing the stability necessary to sustain life. Unfortunately, his warnings are ignored by the authorities who are planning to phase out nature altogether. Freaky winds, icy earthquakes, and mutant anemones plague the landscape. After a wildly devastating storm, Banshooo has a vision revealing the connection between Ooolandia and the Unseen World–a connection that lies deep within and far beyond all that is seen. This connection is vital to Ooolandia’s survival, and it is fraying. He realizes he must take radical action. Along with his quirky sidekick (a one-off of unique appearance whose primary interest is snacking), he sets out on a journey beyond the surface of the Seen to bring back proof of the true nature of nature.

Patricia J. Anderson, recipient of The Communicator Award for online excellence, is the editor of Craig Barber’s Vietnam journal, Ghosts in the Landscape. Her books include All of Us, a critically acclaimed investigation of cultural attitudes and beliefs, and Affairs in Order, named best reference book of the year by Library Journal. Her work has been published in the following periodicals: The Sun, Tricycle, Chronogram, Ars Medica, Glamour Magazine, and Rewire Me.com. She also produces content for the American Museum of Natural History and the Capital Museum. She lives with her family in New York’s Hudson Valley.

Mary: Threshold is a wonderful and original tale about a difficult subject: ecological collapse. It’s not preachy but is a tale of warning. It’s also funny and endearing. The two main characters are a wise monkey named Banshooo and his sidekick, humorous Taboook–called a one-off, or, he doesn’t fit into a category of any one species. How did you come up with these characters?

Mary: Threshold is a wonderful and original tale about a difficult subject: ecological collapse. It’s not preachy but is a tale of warning. It’s also funny and endearing. The two main characters are a wise monkey named Banshooo and his sidekick, humorous Taboook–called a one-off, or, he doesn’t fit into a category of any one species. How did you come up with these characters?

Patricia: I’m so glad you like it. About these characters… I know it’s a cliché when writers say the characters wrote the story but I have to admit, these beings came quite alive to me and sometimes it felt almost as though I was interacting with them. I started with Banshooo and it became clear very soon that he had a buddy who had a lot to say, and a wise mentor, and also a brilliant colleague, and then Durga appeared and it grew from there.

(I had a lot of invisible friends as a child and most of them were animals so maybe that figured in.) The different characters represent the real-world divisions, assumptions, and beliefs that divide us.

Mary: The novel is set in a world called Ooolandia, which has similar environmental issues as our planet does while still being far different with fantasy elements. How did you build this world?

Patricia: The allegorical nature of the fable felt right from the beginning. From Aesop to Animal Farm we’ve used fables to illustrate important truths in an entertaining and accessible way and that’s what I wanted to do with this story. And although the fable is sometimes thought to be a rather outdated literary genre, it is, in fact, alive all around us in one medium or another. Animated feature films, super-hero adventures, graphic novels, books and films like The Life of Pi and The Shape of Water, all are, basically, fabulist stories using beasts and animals to illustrate a moral or a lesson about human behavior.

Once I had the form it was a matter of furnishing it or, you might say, designing the set, taking our own society as a basis for the Seen world. It was the Unseen world that presented more challenges because, while certainly imagined, fantasy worlds must make sense within their own sphere, otherwise readers will lose interest. (And for good reason. If anything is possible, there’s no point in following a narrative line.) For the Unseen, I used the ancient Vedic creation mythology and descriptions of metaphysical worlds as a basis. And if you think about it, current research in quantum physics is beginning to look very much like a lot of those “mythological” schematics. Maybe they knew something we don’t yet know.

Mary: Very interesting! Can you explain to readers what is going on in this novel? What similarities does it have to our world?

Patricia: The dominant ethos in Ooolandia is the philosophy of More-ism. Leadership promotes the exploitation of any and all resources (including the citizenry itself) toward the goal of producing More, always More. Any serious effort to propose other ways to work and live together is discouraged or marginalized. The authorities seek to control all aspects of the society. Environmental degradation is increasing on many levels but the data that reveals how and why this is happening is being suppressed while the development of an unquestioned mechanical technology proceeds unchecked, technology that is aimed, essentially, at replacing the natural world.

(In Threshold, each reference to experiments, research, and technological development is based on actual devices and practices currently being produced and, in some cases, already integrated into regular use in the U.S. and other countries world-wide.)

Another similarity is that so many Ooolandian citizens are dependent on keeping their jobs just to make do. As in our world, many are simply overwhelmed just trying to make enough money to feed and clothe their families, they really don’t have time to consider the hidden disaster that global capitalism is causing, let alone what they might do about it. Unregulated capitalism is really such a cruel system, leaving so many in a state of barely getting by while a few live in extraordinary opulence. (I agree with what Ecopunk writer/editor Cat Sparks said in your interview with her about this being the core of the problem.)

Another aspect of our world that is explored in Threshold involves quantum mechanics and scientific research into the origin and makeup of matter. As we try to understand material reality, we are peeking into some pretty slippery territory where the ways in which we measure these tiny particles actually affects the particles themselves; where our “view” of the thing changes the thing. In the book, Banshooo travels between the Seen and the Unseen worlds, where he learns that matter and consciousness interact.

Mary: I noticed this nod to theoretical physics and, in particular, to David Bohm, with the note that he developed the concept of the “Implicate Order,” based upon the idea that beyond the tangible world is a deeper, implicate order of undivided wholeness and that it was his idea that someday we would “come to recognize the essential interrelatedness of all things and would join together to build a more holistic and harmonious world.” Can you expand on this idea, including the importance of healthy ecosystems?

Patricia: David Bohm was an extraordinary individual. He made major contributions to quantum physics but was also very involved in exploring the nature of consciousness and how the mind influences the ways in which we see the world and how we interact with our environment. He and the Indian philosopher, Krishnamurti, engaged in a dialogue over many years, remarkable not only for the level of erudition they both brought to the discussion but also for a willingness to consider findings often dismissed as marginal by strict scientific standards. I’m not qualified to describe Bohm’s work in any detail (or even generally), but what I do understand is that he proposed that the big question quantum physics has raised about how materiality comes to manifest itself is, essentially, a metaphysical question and we might consider looking toward Eastern models to help mechanistic sciences understand the “quantum soup.” Underlying all of our hard science is a soft reality in which everything effects everything else.

Ecosystems are a prime example of this interrelatedness. We are finally beginning to understand how complicated ecosystems are and how they work to balance and maintain themselves and how we have disrupted that balance in so many disastrous ways. If we could see the natural world as the intricate manifestation of something infinitely complex, something that has, in fact, given birth to us, we might approach it with humility and awe. We might come to work with it rather than against it.

Mary: One reader called the novel hopeful–not at all dystopian yet still realistic in a sense. Do you think it’s important to tell stories that make us feel optimistic about our future?

Patricia: Ursula Le Guin said: “Stories held in common make and remake the world we inhabit… The story we agree to tell about what a child is or who the bad guys are or what a woman wants will shape our thinking and our actions, whether we call that story a myth or a movie or a speech in Congress.”

A key point in Threshold is just that. The world is made of stories (which is also the title of a wonderful book by David Loy). We are hard-wired for narrative. Art, philosophy, science, religion, they’re all stories. Some of us believe one story, some of us believe another, and the story we believe underpins our actions, our sense of ourselves and of the world.

It’s true that many dystopian novels and films with nightmare scenarios about the future leave people feeling helpless in the face of the problems. We’re not helpless, but many people are unsure about what they can do. In this book, the answer is to become aware that we are in a story and the story can be changed. That awareness is the key. It’s the first step toward real change.

Mary: In your mind, how important is it for authors to tell good stories that include ecological themes, and how do we do this without being didactic?

Patricia: I think it’s very important to do it, but how do we keep from being didactic? That’s a good question. It’s hard not to preach. Even if you do just a tiny bit of research, or simply pay attention to news about global environmental conditions and events, you can get so mad you want to grab people by the shoulders and say “What’s the matter with you! How can you not work to establish a green party or make the environment the key factor in every political decision you make?” But, as you may have noticed, people don’t often respond well to anger. Writers who can use their anger to fuel an energetic narrative, that’s the cool move. I have such admiration for novels that actually include ideas and proposals for sustainable technologies. Some of these authors are beyond amazing in their ability to incorporate such ideas into a fascinating story that keeps you reading and makes you want to see such a world come into being. I’m so glad to know that there is a whole collection of ecopunk and solarpunk authors and editors who are establishing a new genre.

Mary: I like the idea of transforming anger into an energetic narrative.

Are you working on anything else at the moment?

Patricia: I’m currently working on an essay about inequality and have resumed work on a half-completed novel about a photographer who becomes obsessed with the idea of living a life free of illusion. She finds this to be another illusion.

And I’m hoping to do a sequel to Threshold wherein Banshooo and his cohorts continue to try and save the natural world. There are so many extraordinary aspects of our world that are, in and of themselves, so amazing they beg to be integrated into a fabulist context where they can be readily understood and still remain totally true.

For instance: Superposition or the quantum entanglement phenomenon that can keep two particles connected even when separated by an entire galaxy. Einstein called it “spooky action at a distance.”

Or neutrinos, which are beyond anything “normal.” In Werner Herzog’s documentary film, Encounters at the End of the World, he interviews Peter Gorham, a physicist working with ANITA, a neutrino detection project based in Antarctica, who says of his work: “…it’s like measuring the spirit world.”

Or the Greater Wax Moth, who can hear better than any other creature on our planet. When glaciers melt, the past is released into the air. I wonder if they can hear it.

Mary: I have read quite a bit about quantum entanglement and find it fascinating. Thanks for these great references. Please keep in touch regarding your future novels!