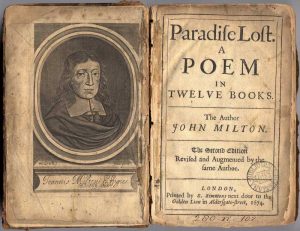

It’s been a while since I have had time to write a new Discover book feature. Partly it is just that this eco-fiction project is entirely voluntary. I also work full-time (in an engaging career) and run a small book publishing company. I want to thank a reader named Dylan for pointing out that Milton’s Paradise Lost should be here on the site. He said, “There has been a strong growth of literary criticism tackling the ecological themes of John Milton’s epic,” and I agree. He also linked to Robert Wilcher’s “The Greening of Milton Criticism,” which points out a facet of eco-literature that is both classic and contemporary, in my opinion:

It’s been a while since I have had time to write a new Discover book feature. Partly it is just that this eco-fiction project is entirely voluntary. I also work full-time (in an engaging career) and run a small book publishing company. I want to thank a reader named Dylan for pointing out that Milton’s Paradise Lost should be here on the site. He said, “There has been a strong growth of literary criticism tackling the ecological themes of John Milton’s epic,” and I agree. He also linked to Robert Wilcher’s “The Greening of Milton Criticism,” which points out a facet of eco-literature that is both classic and contemporary, in my opinion:

Ecocriticism is an offshoot of the environmental movements that developed during the second half of the twentieth century and takes as its field of study literary treatments of the relationship between human beings and the physical environment. When it became established as a recognizable critical school during the 1990s, it was dominated by analyses of British Romantic poetry and literature of the American wilderness. In the present decade, its scope has been deliberately extended to include work from the early modern period. As early as the 1980s, however, the poetry of John Milton had begun to attract attention from critics with an interest in ecological concerns. Paradise Lost in particular became a key text for those who sought to resist the charge that the exploitation of the natural world was licensed by a homocentric Christian tradition based on the Biblical command to ‘subdue’ the earth and ‘have dominion’ over the creatures. An alternative to this tradition has been found in Milton’s conception of the newly created earth as a living organism, his dramatization of Eve’s response to the further Biblical command to ‘dress’ and ‘keep’ the garden of Eden, and his recognition of the ecological consequences of ‘man’s first disobedience’. Recent books and articles have begun to locate ecological readings of the epic and other poems by Milton within the contexts of seventeenth-century developments in land management and materialist philosophy, the origins of modern scientific natural history, and the beginnings of anxiety about such environmental issues as pollution, the treatment of animals, and deforestation.1

I first read the epic poem in high school and, unlike others who were bored, I was enticed and inspired. It was one of the truly fascinating classics I read back then, and it opened my mind quite a bit. My life’s work since has been exploring nature writings in fiction and prose, from old to new.

Though not a religious person like Milton, I completely recognized the decay of nature and the moving away from the Garden of Eden. I would argue that the story of the Garden of Eden is a very strong parable, regardless of how religious the reader is, and one can view the concepts of sin and downfall as the departure from a pristine sense of nature, whether human nature or wilderness; this can be done through a variety of lenses, in my case through one of naturalism rather than religious or supernatural. In fact, stories like these–including Daniel Quinn’s Ishmael–were what inspired my speculative fiction novel Back to the Garden, which looks at people dealing with a climate-changed world. In every sense they start from a beautiful garden and leave it, then go back.

Another article looking at nature in Paradise Lost is by Mary Grace Elliot at Georgia State University:

The natural world depicted by John Milton, particularly in the Eden of Paradise Lost (1674), has long been a point of interest for scholars. The garden itself—to be specific, its trees, flowers, and other plant life—has inspired many books and essays. One essay by Kathleen Swaim deals with Eve’s metaphorical relationship with flowers and the mirroring of Eve’s personal growth with a flower’s biological lifespan. Other works by John Dixon Hunt, Stanley Koehler, and Charlotte F. Otten concentrate on the relationship between the poem and English gardens, both in Milton’s day and in later centuries–specifically the ways in which the poem was influenced by earlier gardens and, in turn, itself influenced later gardens. More recently, works by Diane McColley, Karen L. Edwards, and Ken Hiltner have addressed Milton’s portrayal of nature as it relates to ecocriticism. Few scholars, however, address the role of a personified nature, not simply as setting or metaphor, but as an active participant in the narrative of the poem.2

I find it interesting that the long poem depicts the fall of man, as described in the Bible–and, most particularly, that we see our fall and are the only species who can write, philosophize, and try to make sense of it all. This fall is so often given metaphor, is put in the framework of the disconnection and ruination of nature, and with antagonists that frighten us, regardless of whether or not the villain is us or comes from our imaginations.

This is one book to remain in my cozy old library at home.

1. Provider: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; Content:text/plain; charset=”UTF-8″; TY – JOUR, AU – Wilcher, Robert, TI – The Greening of Milton Criticism, JO – Literature Compass, VL – 7, IS – 11, PB – Blackwell Publishing Ltd, SN – 1741-4113, SP – 1020, EP – 1034, PY – 2010

2. Georgia State University Scholar Works @ Georgia State University English Theses, Department of English. 5-11-2013. “Nature gave a second groan: The Decay of Nature in Paradise Lost and Seventeenth-Century Discussion.”

I’m writing my thesis on this topic–loved what you had to say about it.