Click here to return to the world eco-fiction series

Earth Day 2025

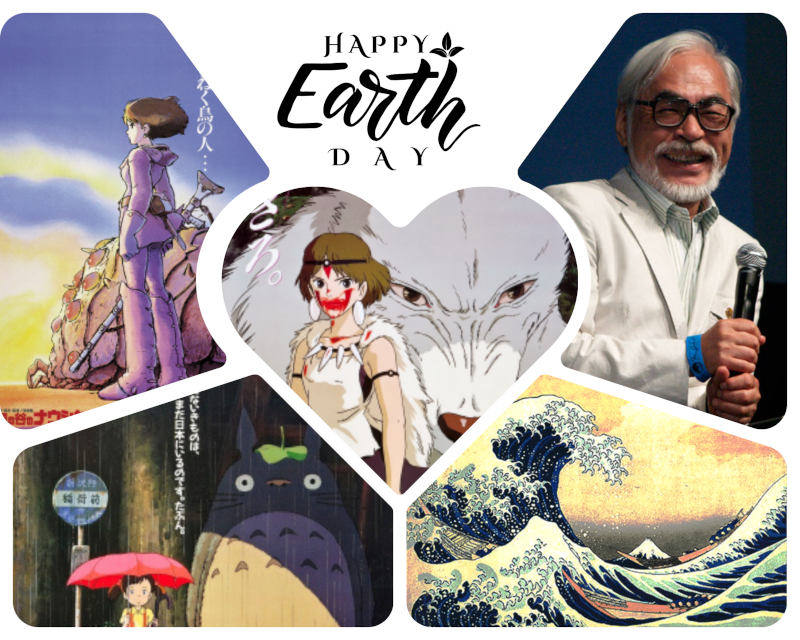

I’m happy to reunite with a colleague from Vancouver days, Isaac Yuen, to celebrate Earth Day 2025. I first met Isaac nearly a decade ago when we participated in an Earth Day climate change and storytelling panel at the West Vancouver Memorial Library. In 2019 we met again with other writers at a Coqutilam, BC’s Western Sky Books event called Earth Day: Writers Respond. Isaac has run Ekostories for 13 years; it’s a site of essays connecting nature, culture, and self. I’ve run Dragonfly for about the same amount of time. This Earth Day celebration focuses on celebrating a commitment to stories and the power of stories about nature, climate, ecology, and our connection to Earth. We tell our own stories but also spotlight major artists whose commitment to storytelling inspires and informs our work and has transformed many others around the world. One of these artists—Japanese filmmaker, manga artist, and animator Hayao Miyazaki—has been working as an artist for longer than either of us has been alive. I’ve always wanted to do a spotlight on him but knew I couldn’t reinvent the wheel; I’ve often turned to Isaac’s website to learn more. Isaac is an essayist and story author. This spotlight focuses on Miyazaki but also covers some of Isaac’s work, including his books, such as Utter, Earth—a celebration, through wordplay and earthplay, of our planet’s riotous wonders.

In the 2019 World Ecocity Summit in Vancouver, I presented a writer’s workshop on eco-fiction, and my first slide quoted Tyrion Lannister: “There’s nothing in the world more powerful than a good story. Nothing can stop it. No enemy can defeat it.” Isaac’s website also has a section on the power of stories: “Stories have the ability to break down walls, to get us to care, to make us think differently, and in so doing, to ignite the fires of change.” We’re just two people in a sea of others who are committed to stories and understand their transformational power. We consistently spotlight other artists who tell Earth stories. Together, along with an ocean of artists making waves, we hope to lift up stories that connect all of us to our planet.

Chat with Isaac

Mary: The first time I met you was at an Earth Day panel about fiction and the environment at West Vancouver Memorial Library in 2017. Then we had an interview at Dragonfly.eco in October that year. Once again we met at Western Sky Books for an Earth Day reading in 2019. And since then, we’ve both moved away from the lower mainland of Canada. What have you been up to since Vancouver days?

Isaac: That first meeting feels like both yesterday and also so very long ago! Since then, I’ve focused on expanding my writing practice and working on short fiction and creative nonfiction at the intersection of nature, science, and art. I’ve had the fortune of attending several writing residencies in Europe that sparked a series of new projects, including the essay collections Utter, Earth: Advice on Living in a More-than-Human World (which I did a reading for at Western Sky Books this past June!) and The Sound Atlas: A Guide to Strange Sounds Across Landscape and Imagination. I co-wrote the latter was with my partner Michaela Vieser, and it’s set to come out in English this fall.

Mary: I miss Western Sky Books. Props to them for allowing local nature writers to host events. That’s cool that you got to go read there again. You run Ekostories, which I find is a great place to explore, and you’ve done some exciting things since we last talked. Can you talk about Ekostories, what led you to create that site, and some of your inspirations?

Isaac: Thanks for visiting the site. Ekostories began more than a decade ago as a a way for me to explore my love for environmentally themed narratives across literature, film, games, music, and art. Initially, I had intended it to be a space to leverage my environmental education degree to promote ecological literacy, but gradually it became more of a creative space to hone my own writing to produce more literary works. With over a hundred longform essays, Ekostories these days serves as an evergreen archive. It seems to be as popular as ever, perhaps because many of the narratives explored are just as relevant today. In recent years, I’ve also been delving into the visual arts, creating graphic designs to highlight the flora and fauna that serve as my inspiration.

Mary: Because this is a world eco-fiction spotlight, I’d love to focus on your writings about Hayao Miyazaki. In 2021, you had a piece titled “The Ecological Imagination of Hayao Miyazaki” in Orion Magazine. You’ve also written multiple articles about Miyazaki in the past at Ekostories. First, how did you first get involved with loving his films, and second, can you tell Dragonfly’s readers more about him? Have you ever spoken to him, and what facets of his life do you find interesting?

Isaac: When I first began Ekostories, I had cited Hayao Miyazaki as one of the chief influences in shaping my worldview. I’m hardly alone in my admiration for him as a storyteller—Wikipedia notes that he is “widely regarded as one of the most accomplished filmmakers in the history of animation.” His work not only opened my eyes to new ways of depicting the natural world, but also unique narrative structures for telling complicated stories where the human and non-human world come together in harmony or conflict. There has been a lot written about the recurring themes in his oeuvre, themes like pacifism, feminism, environmentalism, and artistic craftsmanship. I would encourage anyone who is unfamiliar with his work to watch a film or two of his to get a feel for the multitude of emotional registers he operates on.

For me, perhaps the greatest appeal stems from Miyazaki’s Herculean dedication towards his craft. It’s relatively simple to point a camera at pretty scenery and work the footage into a film, but in animation, where every cell has to be drawn, painted, and painstakingly replicated, this intention requires extreme commitment. Princess Mononoke has something like 80,000 key frames that Miyazaki himself had to draw and retouch by hand. It’s incredibly labour-intensive. But he chose to do this because every scene, whether it be part of an intense battle or a lingering shot on a quiet pool, was vital to the story he wanted to tell, the mood he wanted to evoke, the theme he wished to convey. No shortcuts.

I haven’t met or spoken with Miyazaki. In reading a lot of interviews and researching the production processes behind his work, I get the impression he’s not the easiest person to be around. He strikes me as one of those people where the work is his life; he’s infamous for “retiring” after finishing every movie only to unretire before each new film. This can be taken as an inspirational and/or a cautionary tale, depending on your perspective.

Mary: What was it like to be invited to publish a piece on Miyazaki at Orion?

Isaac: I’ve had the good fortune to contribute several pieces to Orion, a magazine that remains one of my literary touchstones when it comes to thoughtful engagement with the more-than-human world. I encourage anyone and everyone to check out their work, which is always ad-free, community-supported, and so desperately needed in our present times.

Compared to the past shorter pieces I did with then, The Ecological Imagination of Hayao Miyazaki feature took a bit of back and forth to find its shape. I think the challenge came in finding a good mix of the personal and the explanatory so that the essay was accessible not only to Studio Ghibli fans or cinephiles but a wider audience that might not be versed with Miyazaki’s storytelling style. I also wanted to pair the work with some film images, which luckily had just been made available at that time for use. I’m eternally grateful for editorial feedback from Kathleen Yale, now Orion’s digital editor, along with the keen eye of Nick Triolo, the former digital editor, for making the piece come alive for the online space.

Mary: Can you tell us about your experience doing the Imaginary Worlds podcast on Miyazaki?

Isaac: Eric Molinsky, the host of Imaginary Worlds, initially approached me during the early stages of thinking up an episode that would touch on the environmental themes in Miyazaki’s films. He had come across my essays on Ekostories and liked that that they weren’t treading the same ground, so we got to chatting and decided a roundtable format would work well. I thought of environmental journalist and writer Emma Marris, having enjoyed the ethical dimensions in her books Rambunctious Garden and Wild Souls, both of which delved into the human construction of nature and the natural. We were also fortunate to find environmental scholar Yuan Pan from the University of Reading to round out the discussion. It was a lot of fun, to probe into the thematic, philosophical, and aesthetic leanings of Miyazaki’s work through a series of very different lenses. It was also great that we were all Miyazaki fans!

Mary: Your other articles at Ekostories go back further, such as exploring The Nausicaä Project in 2015, which has seven detailed volumes covering the graphic novel. My spouse and I recently rewatched the film, and because I’d been focusing on eco-weird and horror involving natural decay, fungi, and then healing/composition, I saw the movie in a new light. Have you ever had new ideas about the movie since the first time you saw it?

Isaac: This reminds me that I’m due for a rewatch of the film and a reread of the graphic novel. Even as a kid watching the movie for the first time, I found the opening scene in the Toxic Jungle engrossing: here’s an alien landscape filled with insects and fungi that normally reside on the micro level, now made gargantuan and deadly. Yet Nausicaä finds such solace in this terrifying and grotesque space, sees such beauty in its inhabitants. I think that came to be a formative scene for me.

The world of Nausicaä is also super interesting, isn’t it? It’s different than most post-apocalyptic settings, as those usually depict a diminished nature. But in Nausicaä’s world, nature is a dominant force, seemingly a spirit of vengeful destruction. Humanity is the one facing extinction and living in twilight, barely hanging on. The graphic novel would go beyond the film to delve deeper into this human/non-human interplay, as Miyazaki grappled with why his rendition of nature seems to harbour agency and be purpose-driven (spoilers: it’s because it is not natural at all), and he does this in a very powerful way that makes sense for both on a narrative level and his own personal level. One of the things I loved about the graphic novel is that it is not only Nausicaä’s journey, but also Miyazaki’s own evolution as a thinker over the decade he took to write and draw it.

Revisiting Nausicaä in recent times, I’m again drawn to the complexity of its world-building, which would later resurface in Princess Mononoke. It continually reminds me that it’s possible—no, necessary—to hold two contradictory ideas in one’s head. Nature can be serene and dangerous. Human beings are capable of great kindness and great cruelty. We can do harm and we can also make amends. To live is to choose, and in that choosing lies freedom and hope and change, even in a bleak and damaged world.

Mary: I’ve often thought of the duality of nature, kind of in the terms of tragic and beautiful. The world of Nausicaä is completely immersive, too! In 2013, you wrote about Princess Mononoke, by Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli, calling it one of the best environmental movies in history. Because it’s interesting to learn more about these world spotlight’s backgrounds, can you explain Shintoism and animistic deities that acted as guardians of the forest in the story?

Isaac: It’s such an epic! How can one not get swept away by the cursed quest of Ashitaka, the plight of San and her wolf kin, the desire for Lady Eboshi to create a new utopia for her people? Miyazaki infuses his human and non-human creations with their own motivations, each informed by their own worldview that pits them against one another, culminating in events that can only end in tragedy. And all of this occurring in a world where every rock and leaf contains a kami, or a deity, a spirit that transcends Western definitions of living and non-living.

I’m by no means an expert on Shintoism. But I was on an extended research trip with my partner, Michaela, across Japan a few years back. We made it a point to visit the island of Yakushima, the place that served as chief inspiration for the forests in Mononoke. There was a definite presence emanating from the old-growth cedars there, left to grow and witness the world over centuries and millennia. The interesting thing is that Yakushima is not some pristine, untamed wilderness; it has a long and documented history of resource extraction, as wood from the forests was harvested for export to other islands (for making shingles, mostly!).

Isaac (cont.): I think what served Princess Mononoke was its groundedness. At its heart, it’s a period piece anchored in Japan’s Muromachi period (1336-1573), inspired by real landscapes like Yakushima, depicting the plight of common folk embroiled in strife and revolution. The film’s world-building captured the weight of that phase of industrialization and environmental upheaval. Of course, Miyazaki portrayed different aspects of nature through fantastical avatars, but this is also in line with Shinto interpretations of kami of great power, each of which can be benevolent, wrathful, or utterly incomprehensible. By pitting these various forces against one each other, Miyazaki calls to attention how futile it is for humanity to wage war against nature, against life itself. No one wins in the end, nor can they return to the way things were, and in the trajectory of that message lies the movie’s power.

Mary: I hope you don’t mind that I added a photo of that forest above! In your 2012 essay about My Neighbour Totoro, which takes place in the Japanese countryside, of which you wrote, “where an easy balance is struck between cultivated lands, human habitation, and untamed wilderness.” You saw this as an adult, unlike Nausicaä, which you first watched as a younger person with your aunt and a cousin. How did Totoro fulfill some of that earlier nostalgia and give you new ideas?

Isaac: Can we be nostalgic about things we have never experienced? It’s a question I’ve been thinking about a lot recently. These days I see younger generations who were born in the digital age seeking comfort in analogue media and culture. I think there’s always a tendency for us to yearn for something we never knew, and with that lure of novelty comes some element of romanticization. A lot of things seem better outside their context. They may be. Or they may not.

While in Japan, we observed practices of satoyama, the form of long-term community stewardship of local countrysides similar to what was seen in Totoro, which reputedly took place in 1950’s post-war Japan. We even saw efforts to promote the concept of satoumi, which is similar to satoyama but applied to marine and coastal regions. The downside of these systems is that they require a lot of dedicated labour and generational knowledge to sustain, and many people have moved away in recent years to larger cities in pursuit of different lifestyles. On the other hand, we also spoke with some who have grown dissatisfied with the trappings of modernity and are seeking to return to older, more sustainable ways. It was interesting to observe these swings in attitudes, in both directions, for different groups and generations.

On the note of generations, I think watching Totoro as an adult gave me a different vantage point than someone who grew up with it. I feel I was able to see the children as children without needing to embody their experiences. Totoro is so often seen as a quintessential children’s film, but for me, it’s almost more of a movie for parents. I found myself noting how often Satsuki and Mei’s father encourages his daughters’ imagination, how gently he nurtures their relationships with the environment. It’s so refreshing to see adults portrayed as patient, supportive figures instead of dismissive, antagonistic forces. How wonderful it is for adults to believe in their children’s experiences, to guide them from their perspectives!

Mary: It’s totally wonderful to see that. That’s an interesting point about being nostalgic for things we haven’t experienced yet. Have you written or read other articles about Miyazaki that you would like to boost?

Isaac: So much has been written about Miyazaki and his work that I’m sure I’m missing some. I think the 2013 documentary The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness by Mami Sunada is a good place to start. It goes into Miyazaki’s worldview, his relationship with the other Studio Ghibli founding members, and his process working on what was supposed to be his final film at the time, The Wind Rises.

For cinephiles, the late Roger Ebert did a short piece on Miyazaki that was quite insightful, particularly on the topic of pacing and the concept of ma, an intentional emptiness inserted into the narrative. But my favourite interview has to be the 1995 conversation Miyazaki did with Comic Box just after finishing the Nausicaä graphic novel. The translated title is called I Understand Nausicaa a Bit More Than I Did a Little While Ago. It’s a fascinating window into his evolving thoughts on this story that consumed him for more than a decade. And on a related note, Nausicaä and the Fantasy of Hayao Miyazaki (PDF) by Andrew Osmond is a fantastic in-depth analysis; I referred to it while penning my Nausicaä retrospective on Ekostories. But these latter two articles might only be insightful after reading the graphic novel!

Mary: Are you working on anything else at the moment?

Isaac: There are no shortage of projects or project ideas; it all comes down to realizing visions to fruition! As I mentioned in the beginning, Michaela and I are currently finishing the final proofs for our joint book The Sound Atlas, set to come out this fall. It’s inspired in tone by one of my favourite books, Judith Schalansky’s Atlas of Remote Islands: Fifty Islands I Have Never Set Foot On and Never Will, and is a collection of essayistic vignettes featuring the stories of unusual sounds around the world and beyond.

We’re also in the research phase for a new essay collection on ocean, tentatively titled The Atlas of Deep Sea Features: Stories and Soundings from the Depths. We thought now is a good time to tell the stories of these little-known spaces, with the rising interest in deep-sea mining and other extractive activities.

As for smaller projects, I’ve just completed a deep-dive interview over at The Burning Hearth, a blog by speculative author Constance Malloy, celebrating the one-year anniversary of my debut collection Utter, Earth. And I recently finished contributing a short piece to The Systems and Futures section of Public Books, exploring the declining value of post-apocalyptic parables in our modern age and what alternatives might offer better ways forward, so look for that soon!

Finally, I’m also working these days in the graphic design space to create artworks of resistance that are inspired by nature. It seems that more than ever, we need radical wisdom from beyond our human world, and that sometimes, words alone may not be enough.

Mary: You sound pretty busy, so I’m very happy you had time to reconnect and talk about your work with Miyazaki and other fantastic writings. I wish you the best on your current and future projects. I’ll definitely be checking in on Ekostories to find out more. Also, happy Earth Day!

About the Author

Isaac Yuen’s short stories and creative nonfiction has appeared in AGNI, Gulf Coast, Orion, Pleiades, Shenandoah, The Pushcart Prize Anthology, wildness, and other publications. He is the author of the essay collection Utter, Earth: Advice on Living in a More-than-Human World (West Virginia University Press, 2024) and co-author of The Sound Atlas: A Guide to Strange Sounds Across Landscapes and Imagination with Michaela Vieser (forthcoming via Reaktion Books in Fall 2025).

Image Credits

Images used in page banner: