Click here to return to the world eco-fiction series

About the Book

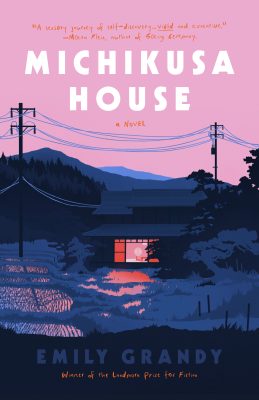

In Michikusa House (Homebound Publications, 2023), Winona Heeley spent the last year of recovery from eating disorders in rural Japan, at Michikusa House, alongside one other full-time resident: Jun Nakashima. Like Winona, Jun was a recovering addict and college dropout. While they bonded over rituals of growing their own food and preparing meals, they changed each other’s lives by reconstructing long-held beliefs about shame, identity, and renewal. But after Winona returns to her Midwest hometown, Jun vanishes. Two years pass and Winona, seeking revival through gardening, accepts a job as a groundskeeper at a local cemetery…and begins searching for Jun Nakashima once more.

Chat with the Author

Mary: I love your your website’s About page, which says that your “writing is a celebration of and an invitation to reconnect with the more-than-human world.” I think we all need these stories right now. Can you describe what led you to become a writer of literary fiction with an ecological focus?

Emily: I became an ecologically focused writer in a roundabout way, and it began with a health crisis. In the Author’s Note at the end of Michikusa House, I mention that this story is somewhat based on true events, so the story is a very personal one. The book offers a glimpse into how I learned to connect with the more-than-human world as a direct result of my own healing journey. The backstory of the main character, Winona, is that she has just recovered from a series of eating disorders. But in the process of recovery, everything else in her life stopped. She had to drop out of university and was on medical leave for almost two years so she could focus on her health. In that time, she heals physically but struggles to find new meaning in her life—a reason to get better. This is where the book begins, when Win’s mother decides to send her overseas to stay with a friend in the Japanese countryside, where she learns how to grow her own food and cook in concert with the seasons. For the first time, Win begins to understand something she never realized before: food connects us with every other living thing. Jun, a young intern working on the farm, puts it best: “If not for sun and rain and insects and many hard-working people, so many things working together in just the right way, we wouldn’t have ingredients to make a delicious soup like this one to warm us on a cold day.”

For me, entry into ecological awareness happened exactly in the same way. After years of struggling with eating disorders, I had to relearn—very literally—how to eat. American food culture is not a great model in that respect, so I looked to other food cultures around the world for guidance. How do other people eat who have not been exposed to Western influence? With that question in mind, I became especially interested in the Indigenous food cultures of North America, which made me realize that a lot of the foods we eat commonly today are not native to the Americas. That got me curious about what foods are native to where I live. Apart from the obvious answer—the foods we traditionally associate with Thanksgiving—it wasn’t an easy question to answer because that example accounts for only a tiny percentage of the immense variety of foods and medicinal plants originally cultivated and harvested in this country by its native peoples. The original inhabitants of this land had ingenious ways of encouraging food plants to grow in what are sometimes, today, known as food forests—complex ecosystems of perennials including fruit and nut trees, herbaceous and tuberous plants, etc. From there, that got me interested in native plants and animals more generally. In short, it was food that connected me to everything.

Mary: I have also experimented with eating food native to my locale, and it’s a great idea in permaculture to also grow native plants, if possible, because they adapt well to the environment. You’ve written two engaged novels: Cupido Cupido (not yet available for purchase) and Michikusa House, which we’ll talk about today. How do each of these novels relate to the natural world?

Emily: Apart from growing food on a small family farm in Japan, Winona is also given the opportunity to go foraging for wild edible plants. This ancient practice of gathering sansai still exists today in rural areas of Japan. Her harvesting guide, Shoko Hanada, explains how entwined this cultural practice is with the shifting seasons: “To gather sansai, you must notice when buds grow and swell, when berries ripen, when mushrooms push up.” But this practice, and the knowledge of where to find and how to identify these special plants, is lost when people move away from their ancestral homeland, often to cities. Shoko tells Winona that “Health comes only from knowledge of all parts of many types of plants: buds, leaves, roots, flowers, fruits…Here, we say that city people are unwise to rely on only a few cultivated plants for eating and for healing and medicine.” When Winona returns to America, she decides to leave university for a second time to pursue a groundskeeping job at the historic cemetery beside her house. Her reasoning is simple. She says, “I miss getting up close and personal with earth, like I did in Japan. I miss holding a seed the size of a grain of sand in my palm, watching the miracle of seasonal rebirth as it sprouts and matures into something edible. I miss growing my own food.” While there, she begins to appreciate the subtleties of urban nature, which is no less interesting, complex, or valuable an environment than, say, a world heritage site or a national park. It’s a theme I’m really passionate about—respecting the value of urban nature. While many of us understand this value intuitively, science is starting to catch up. As I’m writing this, The Guardian just did a feature on a study published in the Science of Total Environment on how living closer to urban green spaces promotes healthy aging in city-dwellers by helping to maintain telomere length.

My forthcoming novel, Cupido Cupido, was a finalist for the PEN/Bellwether Prize earlier this year and, like all of my writing, contains similar eco-forward themes. In this book, a sixteen your old boy, nicknamed Egg, spends his summer vacation on his grandfather’s farm in rural Kentucky and ends up discovering a species of ground fowl on the property, thought to have gone extinct back in the 1930’s. This book dwells at the intersection of where science meets—or confronts—culture. Literally. A team of ornithologists comes to stay on the farm to research the birds and how the townspeople respond to that and how people address living alongside this species, for better or worse, is a theme that runs through the book.

Mary: That sounds awesome, and as a Kentuckian by birth, I’ll have to check it out. What else is happening in Michikusa House?

Emily: In addition to its ecological focus, virtually all my writing, Michikusa House included, explores current scientific and medical research in some way, both its strengths and its shortcomings. Although my own background is in medical research, I think we tend to over-rely on science and technology to offer us solutions to ecological and climate problems, when what might better serve us is a shift in perspective and values. In Michikusa House, the characters grapple with this issue directly. One, an engineer, is said to “[see] the world as an engineering project, an object you can disassemble into its constituent parts which, once identified, can be fully understood. But reductionism only works for objects that can be cleanly separated; it’s an impractical method to apply to living, flowing, messy biology.”

The best example I can give to illustrate how much medical and biological science overlooks is this: think of the person (other than yourself) who you know best in the world. A spouse or your best friend. Now imagine your loved one is enrolled in a scientific study in which the researchers’ aim is to understand everything about that individual. Every day, for a full year, let’s say, scientists from many disciplines will take notes and measurements: blood pressure, cholesterol, hand preference, psychological questionnaires, dream diaries, food intake and exercise, a biographical sketch, genetic profiling, you name it. At the end, all the scientists pool their data and write a report describing all the metrics they collected and analyzed about your loved one. Their combined conclusion is that they now have a pretty good idea of who that person is. But would you say that even after a year of interaction those scientists know your loved one better than you do? Probably not. Would you even be a little insulted if they claimed to know your loved one better than you do? Probably! Why? Because you are the one who has a relationship with that person. You’ve known them longer, you have a history together. My point is this: scientific knowledge, via numbers, rates, and metrics, though undeniably useful and essential to human flourishing, forms an incomplete picture. It is just one way to know something. Forming a relationship is another way. Developing relationships is what enriches our lives and gives deeper meaning to our daily interactions. Indigenous or generational knowledge is also increasingly recognized for its essential wisdom. These ways of knowing can introduce us to the fullness, the wholeness of every species, body of water, or stretch of land. After all, it’s not just people who are complex. Every living thing exists within an intricate ecosystem that is just as nuanced as the life and spirit of your loved one. This sort of knowing, built over long periods, is what facilitates understanding, compassion, and respect for other beings.

Mary: What you explain here reminds me of how fiction and creative nonfiction can also offer a deeper insight to ecological and climate changes, much more so than data bits, which I read often from artists and authors developing a relationship with their readers through personalized knowledge and interactions. I think it’s important to note that your novel delves into not only food security but culinary rituals, gardening, and even eating disorders. While taking place partially in Japan, the novel seems to address American food culture and nutrition science as the story moves back and forth between the the two countries. Can you talk some about this? Do you notice healthier food systems and nutrition in Japan?

Emily: I had already developed a longstanding love affair with Japanese food traditions and regional cultures that spanned more than a decade before I began writing this book. It truly was learning about food cultures other than my own, especially those of the Japanese people, that taught me not only how people traditionally eat (i.e. by consuming what grows where they do) but how to respect and give thanks for the food we eat and the land it comes from. Japan has very distinct regional practices and cuisines in large part because the archipelago stretches almost 2,000 miles from north to south and ranges from sub-tropical in Okinawa to a cold, continental climate in Hokkaido. For Michikusa House, my research was more prefecture- and season-specific and delving into the practices surrounding foraging culture.

That said, this book barely scratches the surface of Japanese cuisine. I would have loved to include more detail about the distinct food traditions on Kyushu (the island where the novel takes place). Each ingredient has its own rich history of use and preparation. There are also special food traditions surrounding holidays and ceremonies which failed to make it into this novel. Unfortunately, that nation-wide level of respect for individual ingredients and those who know how to cultivate them is simply not present in America.

Mary: Another cool aspect of the story is that the main character, Winona (or Win), is currently renting a house near a cemetery. I like how she gets peace from the place. I do too, whenever I visit relatives who have passed away. Specifically, a cemetery was on my old running route, and I used to run by it and then through it because it made me feel, in a weird way, close to lives once lived, similar to relatives I loved very much who have passed away. What inspired you to provide a cemetery as one of the locations central to the story?

Emily: I lived in the United Kingdom for several years and always loved English churchyards with their small, overgrown cemeteries, and their old, gnarled trees and crumbling, weather-beaten headstones. But for cultural or possibly superstitious reasons, people tend not to visit these places. You can visit a cemetery and be the only guest there, so I find them to be especially peaceful and quiet places, especially in an otherwise urban setting. For these same reasons, they tend to be sanctuaries for wildlife! Even though I’ve always lived in mid to large cities, I feel most at peace when among wild things. I need tall trees and birdsong and the sound of wind rustling the leaves in order to thrive. So, in addition to local parks, I tend to gravitate to cemeteries when I want to step away from the bustle. I think cemeteries are underappreciated as green spaces, though I know quite a few are trying to change that image. I wrote a piece about that titled “Living Amongst the Dead”, published just last month in The Wayfarer magazine. You can find the link to it on my website.

Mary: That’s a lovely description of English churchyards. Is there anything else you would want to add?

Emily: After Cupido Cupido, I’m planning on releasing a YA eco-dystopian trilogy, so keep an eye out for that. For updates on these releases and other publications, be sure to subscribe to my newsletter!

Mary: Thanks so much, Emily. I really enjoyed our conversation and am looking forward to your trilogy!

About the Author

Emily Grandy is an award-winning novelist and editor based in the Midwest. She writes well-researched literary fiction and nonfiction with an ecological focus. Her writing is a celebration of and an invitation to reconnect with the more-than-human world. Her debut novel, Michikusa House, was awarded the Landmark Prize (Homebound Publications). Her second novel, Cupido Cupido, was a finalist for the PEN/Bellwether Prize for socially engaged fiction in 2023. Her other writing has appeared in both academic and literary journals and has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize.

Before she became a biomedical editor, Emily did clinical research for a leading academic medical center in Cleveland, Ohio. As a former scientist, Emily’s writing aims to communicate science-based knowledge through storytelling. As an artist and environmental advocate, she hopes to help heal our relationship with the more-than-human world. Emily has lived in many places, both in the U.S. and abroad, but always gravitates back to the Midwest and its Great Lakes. She currently calls Milwaukee, Wisconsin home.

Great interview. Thanks for bringing this to light. Base on her descriptions here, Emily’s books must be very interesting and well written. Looking forward to reading her work.