Click here to return to the series

In June, we travel to a fictional place in China called Silicon Isle, based on the real town of Guiyu, in the Chaoyang district of Guangdong province. Author Chen Qiufan takes us there with his novel Waste Tide. I am grateful to Chen for answering my questions about the book and for telling this story, which is all too real and something many of us might not be aware is happening. The villages making up Guiyu were once rice-growing but now, due to pollution from electronic waste sent to this area for recycling, are unable to produce crops. The river water is also not drinkable. Cleanup efforts began to take place in 2013, with the “Comprehensive Scheme of Resolving Electronic Waste Pollution of Guiyu Region of Shantou City”, and in 2017 most of the workshops where workers dealt with a toxic environment were merged with larger companies, but many still remain and are not cleaned up. According to Wikipedia:

Many of the primitive recycling operations in Guiyu are toxic and dangerous to workers’ health with 80% of children suffering from lead poisoning. Above-average miscarriage rates are also reported in the region. Workers use their bare hands to crack open electronics to strip away any parts that can be reused—including chips and valuable metals, such as gold, silver, etc. Workers also “cook” circuit boards to remove chips and solders, burn wires and other plastics to liberate metals such as copper; use highly corrosive and dangerous acid baths along the riverbanks to extract gold from the microchips; and sweep printer toner out of cartridges. Children are exposed to the dioxin-laden ash as the smoke billows around Guiyu, and finally settles on the area. The soil surrounding these factories has been saturated with lead, chromium, tin, and other heavy metals. Discarded electronics lie in pools of toxins that leach into the groundwater, making the water undrinkable to the extent that water must be trucked in from elsewhere. Lead levels in the river sediment are double European safety levels, according to the Basel Action Network. Lead in the blood of Guiyu’s children is 54% higher on average than that of children in the nearby town of Chendian. Piles of ash and plastic waste sit on the ground beside rice paddies and dikes holding in the Lianjiang River.

About the Book

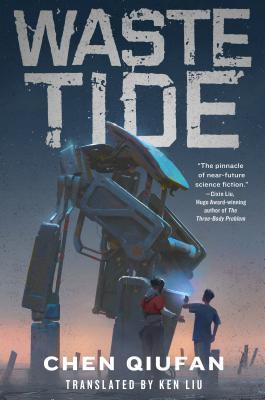

Waste Tide was translated by Ken Liu, who brought Cixin Liu’s Hugo Award-winning The Three Body Problem to English-speaking readers. This sci-fi novel is chilling as it paints an eerie picture on where capitalism leads: class divisions, unregulated technology, and environmental and health degradation, including climate change. According to Amazon, the novel is a “thought-provoking vision of the future,” but I think it is also a reflection of a horrible present.

Waste Tide was translated by Ken Liu, who brought Cixin Liu’s Hugo Award-winning The Three Body Problem to English-speaking readers. This sci-fi novel is chilling as it paints an eerie picture on where capitalism leads: class divisions, unregulated technology, and environmental and health degradation, including climate change. According to Amazon, the novel is a “thought-provoking vision of the future,” but I think it is also a reflection of a horrible present.

Mimi is drowning in the world’s trash. She’s a waste worker on Silicon Isle, where electronics―from cell phones and laptops to bots and bionic limbs―are sent to be recycled. These amass in towering heaps, polluting every spare inch of land. On this island off the coast of China, the fruits of capitalism and consumer culture come to a toxic end. Mimi and thousands of migrant waste workers like her are lured to Silicon Isle with the promise of steady work and a better life. They’re the lifeblood of the island’s economy, but are at the mercy of those in power. A storm is brewing, between ruthless local gangs, warring for control. Ecoterrorists, set on toppling the status quo. American investors, hungry for profit. And a Chinese-American interpreter, searching for his roots. As these forces collide, a war erupts―between the rich and the poor; between tradition and modern ambition; between humanity’s past and its future. Mimi, and others like her, must decide if they will remain pawns in this war or change the rules of the game altogether.

An accomplished eco-techno-thriller with heart and soul as well as brain. Chen Qiufan is an astute observer, both of the present world and of the future that the next generation is in danger of inheriting.

– David Mitchell, New York Times, bestselling author of Cloud Atlas

Chat with the Author

Mary: What led you to write Waste Tide?

Chen: Back in 2011, when I visited my hometown Shantou and met my childhood friend Luo, he mentioned a small town about 60 kms away from where we lived, Guiyu. Apparently, the American company he worked for had been trying to convince the regional government to establish eco-friendly zones and recycle the e-waste, but some local authorities had been standing in their way.

“It’s difficult,” he said, a little too mysteriously. “The situation over there is…complicated.” I knew the word complicated often meant a lot.

Something about his speech caught the attention of the sensitive writer’s radar in my brain. Intuitively, I realized there must be a deeper story to uncover. I took a mental note of the name Guiyu, and later it became a seed of the book.

Mary: Your novel addresses these issues of e-waste and all the greed and class struggles that go along with it. What is your experience in seeing this play out in an area similar to Silicon Isle, in China?

Chen: Most of the description of local life is real. I visited Guiyu myself and tried to talk to the waste workers, but they were extremely cautious around me, perhaps fearing that I was a news reporter or an environmental activist who could jeopardize their work. I knew in the past that reporters had snuck in and written articles on Guiyu, articles which ended up pressuring the government into closing off many of the recycling centers. As a result, the workers’ income was significantly impacted. Although the money they received was nothing compared to the salary of a white collar worker in the city, they needed it to survive.

Unfortunately, I could not stay for any longer. My eyes, skin, respiratory system, and lungs were all protesting against the heavily polluted air, so I left, utterly defeated. I put all my real feelings and experience in the novel.

A few days later I returned to Beijing. My office there was spacious, bright and neat, equipped with an air-purifying machine, a completely different world from the massive trash yard that I had witnessed. Yet, sitting there, I could not get that tiny southern town out of my head. I had to write about it.

Waste Tide could not be simply reduced to black and white, good and bad: every country, every social class, every authority, and even every individual played an important part in the becoming of Guiyu. All of us are equally as responsible for the grave consequence of mass consumerism happening across the globe.

Mary: It seems around the world we see Indigenous people working jobs, or living in or near areas of waste, dangerous to their health. How is this something that you feel fiction can address when it seems sometimes that factual reporting cannot get through to people?

Chen: I think it came to a tipping point when people began to realize how severe the problem is. The pollution has been there for decades, maybe for centuries―the process of accumulation accelerates as technologies develop. Humans didn’t get smart enough to solve the problem before the waste turned to themselves. Technology might be the cure, but fundamentally it’s all about the lifestyle, the philosophy, and the values we believe in. As in China, the issue was uprising during the last four decades, along with the high speed of economic growth. We try to live the “dream life” as Americans, but we have 1.4 billion people.

China has already replaced America as the largest producer of e-waste simply because we are affected by the consumerism ideology. Everyone purchases newer, faster, and fancier electronic devices. But do we really need all those things? All the trash that China fails to recycle will be transferred to a new trash yard, perhaps somewhere in Southeast Asia, Africa, or South America. If we continue to fall into the trap of consumerism and blindly indulge in newer, faster, more expensive industrial products, one day we may face trash that is untransferrable, unavoidable, and unrecyclable. By then, we will all become waste people.

The air, water, soil, and even the food was found polluted or even toxic. The government tried very hard not to repeat the old path of the western world like London or Los Angeles, but it always takes longer to recover than to pollute the environment. So I think both cultural authenticity and futuristic imagination are important to me since I try to use the narrative of science fiction to resonate and evoke the emotional and cognitional response of people on the most urgent and relevant realistic issues around us. Hopefully I did it in a right way.

Mary: I think you succeeded! The story takes place in the near future, but it also addresses the same pattern of problems we already see. Do you think things will ever get better as far as the way we deal with natural resources, manufacturing, and the way we dispose of things? I don’t think many people are aware that a lot of our e-waste goes to China to be recycled, nor about how toxic it is.

Chen: Definitely, even if it’s not obvious and remains invisible. Actor-Network Theory (ANT), founded by Bruno Latour and Michel Callon, acclaimed that non-human actors, such as waste, should be seen as just as important in creating social situations as human actors. Waste is profoundly shaping and changing our society and way of life. Its outputs cannot be predicted by its inputs. Our daily mundane world always treats garbage as a hidden structure, together with its whole ecosystem, beyond our sights, while maintaining the glorious outfits of contemporary life. But, unfortunately, some take advantage of it while others suffer from it. Class distinctions, economical exploitation, international geo-politics in the e-waste recycling procedures—for example groups and power—must constantly be constructed or performed anew through complex engagements with complex mediators. There is no stand-alone social repertoire in the background to be reflecte off, expressed through, or substantiated in interactions. We have to see the reality.

Mary: Are you working on anything else right now?

Chen: I’ve been working on two projects. One is co-authoring a book titled AI:2041, with Dr. Kai-Fu Lee. It’s a combination of science fiction and tech prediction about how, according to research, AI would change our world in all aspects. Another project is my second novel, A History of Illusion, set in an alternative history in which the Apollo project failed and the human race turned to psychedelic entertaining; a young man with designer-drug talents tries to explore the secret truth behind his family. Both might come out in 2021.

Mary: Looking forward to these! And, finally, how do you deal with writing and book tours with COVID19 shutting places down?

Chen: During the spring festival I was spending my lock-down hour with my parents. In the first half of February, I was super frustrated and anxious, but then I forced myself to stop following social media and turned to reading and writing. That became maybe the most productive period of time in my life, literally. Since we’ve cancelled all the tours, domestically and internationally, I’ve learned to use Zoom, Skype, WeChat, and some other platforms for giving speeches, having meetings, and live-streaming. It has become the new normal for authors and for everyone else too.

About the Author