Author: © Donna Mulvenna

Type: Prose

Author Links: YouTube, Goodreads, Pinterest, Facebook

“The earth has music for those who listen.” – George Santayana

I see a lot of trees from my office window. Although, I don’t actually have a window. I don’t have walls either. Or a roof. I have a small wooden table, a fold-up chair, and a laptop that sits on an open deck high in the treetops, and nature.

There are also a lot of distractions. More than I ever had in my former office with flickering fluorescent lighting, an air-conditioning unit, people coming and going, a telephone with six lines, and overlooking a busy road. White noise they call it. The scientists that is, who measure the stress-related symptoms that result from a day, in a week, in a year, in a life, listening to background noise.

I can’t say it particularly bothered me because for a few decades I had done a commendable job of blocking it out. In fact, I barely heard any noise that wasn’t directly aimed at me. As for taking regular breaks from looking at my computer screen… I was far too busy for that.

Later, when my indoors office was replaced with the outdoors kind, it was refreshing not to hear a constant hum of an air-conditioning unit, the incessant ringing of phones and the loud rumbling of passing trucks.

“Background noise has the same effect on your hearing that a thick fog has on your vision.”

Instead, what do you suppose I heard the first time I sat outside in nature surrounded by wildlife, a natural breeze, and a running stream? It was – Nothing. All I heard was the clatter of my own thoughts.

My brain had mastered the cocktail party effect, where it can focus intently on one stimulus while effortlessly screening out noises or visual images not relevant to me. Nature had become one of those, something irrelevant because I had so often ignored it. I had unintentionally tuned out the sounds of the natural world.

So, what happened next? I was re-schooled. With the help of some new friends.

It was when I was taking the washing off the line that I heard the loud buzzing of a giant insect. Like many creatures in French Guiana (the French Amazon), it had the potential to be one of the biggest in the world and I didn’t want it caught in my hair. I grabbed a T-shirt from the laundry basket and whirled it wildly above my head. As I turned to walk inside I saw it.

It was one of the most exquisite things I had seen. And it was so tiny. It was hovering in the air without moving in any direction, its little wings pumping at an incredible speed. Its body was a brilliant emerald green, except for its white thighs, and it had a bright metallic blue tail.

In my defence, I grew up in a land downunder where cockatoos say “Gidday Mate,” Kookaburras laugh at you each morning, and Magpies have made dive bombing a favorite pastime, so I had never seen a hummingbird before, much less heard one.

I’m kind of glad they chose to stick around as in the beginning, I made a fatal mistake. I cleared a large area around my home. It took me days to hack back and dig out all the Heliconia and replace it with banana plants, something that was useful – to me.

When I learned the nectar from the Heliconia was one of the hummingbirds’ main food sources, I knew I had unwittingly robbed myself of many treasured appearances. I prayed they might just move to a different plant nearby, at least until I could let the Heliconia grow back, but I didn’t like my chances.

How would we feel if every day we looked forward to a breakfast of scrambled eggs, and one day we woke up and there weren’t any? Would we settle for the diet muesli in the cupboard or duck down to the corner store for more eggs?

On one occasion, because old habits die hard, I was overly focused on my computer screen. I heard an inkling of sounds around me, branches moving, leaves falling and some sort of squeaking. But it wasn’t until I heard the unmistakeable sound of a branch snap nearby that I looked up. And there they were. Almost on top of me.

They were looking at each other as if to say, “Why hasn’t she been moving?” I was staring at them thinking, “Why didn’t I take notice and look up sooner?” They had the most beautiful keen-eyed little faces and I sat mesmerized as their nimble hands reached out to pick fruit.

Suddenly, the tree came to life and the squirrel monkeys leaped and scurried across the branches. A mother a little further back was carrying what looked to be a tiny backpack, a baby probably only a few weeks old.

From that day forth, I listened carefully for rustling leaves, scampering feet, a branch surrendering underweight or the sharp snap of a twig, eagerly anticipating future visits. Not that I had much choice. They are natural exhibitionists that propel themselves through the trees with tremendous gusto before squeaking, “Hey you! We’re here!” as they all vie for my attention.

Green iguanas don’t do that. They prefer a more discrete approach, laze for hours on the same branch and are completely unperturbed by me. I always know where they are now because I can hear the branches buckle beneath their weight. And that’s a good thing because the first time one decided to jump 10 metres to the ground, crashing through leaves, clawing bark and snapping branches on its way down, within only an arm’s reach, I almost had a coronary. I had no idea it was there and was very relieved when it, and its massive claws, sailed past without making contact.

To be fair, wildlife isn’t in the habit of landing on me. Apart from mosquitoes, that is. And with the exception of ants which are the most hostile beasts in the jungle. Everyone else is happy to live by the co-existence rule, which is to give each other space so we can all go about our business.

My treetop office is in a deep valley, the type where inland driven cloud creates a blanket of mist most mornings. I visit it with the same urgency a person reaches for their first cup of coffee each day. The rain comes at me from over the hill on the east. I had always taken an umbrella, because despite setting out on a beautiful clear morning, somehow I always managed to get caught in a downpour. Now, it is rare I bother with an umbrella. I can hear the rain approaching and the speed at which the wind whips through the trees. I know whether it’s the type of rain that falls so hard and for so long it’s going to form puddles or whether it’s the type that stops as suddenly as it starts. That doesn’t mean there aren’t times I get it completely wrong and clatter through the door with sodden clothes, limp hair, and a big smile.

Afterward, I listen to large droplets of rain fall from overhead branches onto the broad flat leaves of the elephant ears and taro plants below, the sound of water rushing over the rocks of a newly swollen stream, the piercing call of a faraway bird, and a different kind of buzz across the forest.

It is a gift to have my hearing back, especially as large tracts of forest are falling deathly silent due to housing development, habitat destruction, and climate change; and skies may fall silent because of illegal poaching and trade of migratory birds.

Initially, I barely heard a bird at all. Within a few days, I could hear a bird but it was just a bird. Now I don’t hear just a bird, I hear an orchestra of a hundred birds and a hundred different birdsongs. Some venture so close I can see their beaks open and their tail bob when they sing. Others prefer to perform from behind a curtain of lush green foliage, and some make just one shrill call as they rocket within inches overhead. Sometimes, I try and sing back and they tilt their heads to one side as if to say, “That’s a new one!”

I listen to pitch, rhythm, length, and non-vocals like humming wings, all of which become clearer, more detailed and more familiar each day. I mean I really listen. Sometimes I close my eyes so that I can block out everything else. Other times, I cup my hands behind my ears and push them forward so I have bigger sound catchers, and I spin my head from side to side because there are so many beautiful and clear lyrics coming from all directions.

I hear so many things I couldn’t hear before, including sudden stillness.

In some parts of the world little birds are known to tease big birds such as eagles, safe in the knowledge they don’t manoeuvre so well. This would be a mistake in the French Amazon because Harpy eagles are definitely built for manoeuvring.

They have rounded wings and a long tail which helps them to navigate in tight spaces, make super-fast turns, and when they flip upside down in mid-flight to pluck monkeys and sloths from branches, they do it with the stealth of a bomber.

I didn’t hear her but I did sense an unmistakable restlessness sweep across the forest, with more calls and more fluttering about on the perches. I could almost imagine the birds sidestepping toward the main trunk and flattening their little bodies against the bark in an attempt to disappear from view. Tension seemed to build, another alarm call, and again, five times over five minutes. I grabbed my binoculars and eventually spotted the source of all this consternation.

She was perched high in a tree looking every bit as intimidating as her reputation suggests. Considered the most powerful bird in the world – imagine claws more powerful than a Rottweiler’s jaws – I took my cue from the wildlife and headed for more cover.

They are positively the scariest looking of all carnivorous birds. It is no secret why it is the Harpy eagle depicted in Greek mythology as horrid winged women with breasts hanging out that swoop down to take humans to the underworld.

I made a conscious decision to tune into nature because it lets me know what is going on around me. Sometimes it is a quiet affair, but there are times when the action really heats up and I might hear the distant voice of a screaming piha along with a host of other wildlife including toucans, monkeys, oropendolas, caciques, tinamous and woodpeckers.

Hearing the sounds of nature is easy if you follow the process, which is to take the time to relax, breathe and be still, give forest creatures time to recover from you crashing headlong into their space, and stay long enough that nature can come forth and begin your re-schooling.

When you listen to nature you become part of it, part of that flow state. It gives you energy, recovery, calm, joy and passion, and I am certain something way beyond my human comprehension.

***

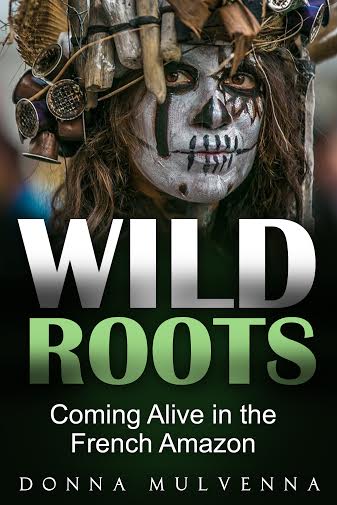

Donna Mulvenna is a horticulturist and author of Wild Roots – Coming Alive in the French Amazon who lives in French Guiana on the fringe of the Amazon rainforest.

Donna Mulvenna is a horticulturist and author of Wild Roots – Coming Alive in the French Amazon who lives in French Guiana on the fringe of the Amazon rainforest.

She left behind decades of corporate writing to write about nature, health, and living simply and sustainably — in essence, her code for living a good life. In her ramblings she hopes to give a glimpse of the fascinating world of the rainforest, reveal its profound effect on each of us and inspire readers to build their own connection with the natural world.

It doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to people who are not her kind of wild, but Donna refuses to own a mobile phone, rarely wears shoes, and is passionate about living on a whole food, plant-based diet. If she can’t be found in her treetop office, swinging in a hammock or somewhere off the coast reading from a sea kayak, you will find her hurtling along untamed rivers in a sprint canoe.