There is an interesting story behind this book. Back when I published an online literary magazine (Jack), and my maiden name was Sands, I worked closely with poet Michael Rothenberg, who at that time was very close to Philip Whalen and later handled his estate. Michael also knew “meat poet” Michael McClure. McClure has always been a favorite poet of mine, along with Whalen and Gary Snyder. You might recognize some of these guys as characters from Jack Kerouac’s novels.

In my very first issue of Jack Magazine, summer of 2000, Michael McClure gave me permissions to republish three poems from his Touching the Edge: Dharma Devotions from the Hummingbird Sangha(now reprinted here). He also sent me the book Specks, shown above.

From Amazon:

Specks assumes the form of a blastula, offering a poetic model of embryonic development that arises from the cellular division known as “cleavage,” transcending the proprioceptive methodology of Charles Olson and entering an Aristotelian realm of metaphysical questions that broach matters scientific and mystical, exploring the properties, powers, and limitations of the physical-poetic body, as exponent of its own consciousness.

Enamored by McClure’s biological poetry, I eventually wrote an article about, “Point Lobos: Animism.” I will copy the article below this entry.

Back to Specks. I was living in California at the time and had known of and occasionally connected with Denise Enck of Empty Mirror Books, who also ran the McClure-Manzarek website. Beat poet Michael McClure often jammed with Ray Manzarek of the Doors. I saw them once performing a night of poetry and music at the Whiskey-a-Go-Go in LA, the first time the rest of the Doors had been back there since Jim Morrison got them kicked out long ago. This was years ago, of course.

That’s just an aside to what turns out to be a weird coincidence. Michael McClure had sent me Specks and signed it to me (Sands is my maiden name). However, when I moved from California, I inadvertently lost the book. Whoever found it sent it to Denise, since she ran McClure’s website. She later wrote to me saying she had the book and recognized my name. I couldn’t believe that book showed up at her doorstep. She sent Specks to my new address. I had felt so badly about misplacing the book but also fortunate to have it end up back with me after all.

So that’s the story of how this book was once lost but is now “found” and returns to my library.

Editor’s Note: Ray Manzarek, who worked with Michael McClure for years, has since died.

The “Point Lobos” article is below:

Point Lobos: Animism

It is possible my friend

If I have had a fat belly

That the wolf lives on fat

Gnawing slowly

Through a visceral night of rancor.

It is possible that the absence of pain

May be so great

That the possibility of care

May be impossible.

Perhaps to know pain.

Anxiety, rather than the fear

Of the fear of anxiety.

This talk of miracles!

Of Animism:

I have been in a spot so full of spirits

That even the most joyful animist

Brooded

When all in sight was less to be cared about

Than death

And there was no noise in the ears

That mattered.

(I knelt in the shade

By a cold salt pool

And felt the entrance of hate

On many legs,

The soul like a clambering

Water vascular system.

No scuttling could matter

Yet I formed in my mind

The most beautiful

Of maxims.

How could I care

For your illness or mine?)

This talk of bodies!

It is impossible to speak

Of lupine or tulips

When one may read

His name

Spelled by the mold on the stumps

When the forest moves about one.

Heel. Nostril.

Light. Light! Light!

This is the bird’s song

You may tell it

to your children.

Poem reprinted with permissions from Michael McClure

Michael McClure is one of my favorite poets. Early in his life he wanted to be a scientist, and like me, was interested in nature and wildlife. Had he not settled in with fellow poets, he may have become what is known as a modern scientist, but I like to think of him as one in a sense, anyway. As a poet and essayist, he incorporates biological themes into his writing. At what was coined the “San Francisco Renaissance,” when the beat generation writers of the east coast merged with the west coast poets at the famous Six Gallery Reading in 1955, McClure read “Point Lobos: Animism” and “For the Death of 100 Whales”–the latter written and read long before Free Willy.

Point Lobos has always been one of my favorite poems. McClure’s awareness of the animal consciousness, and his poems’ organic progressions, lend to his connection with ecology and biology and transference of that visceral undersoul to the reader’s conscience. McClure once said his interest in biology has remained a constant thread through his searching. The piece, as were many post-war avant garde poems, was influenced by French surrealist writer Antonin Artaud, and more specifically as a response in part to the line by Artaud: “It is not possible that in the end the miracle will not occur”.

According to Joanna Pawlik in “Artaud in performance: dissident surrealism and the postwar American literary avant-garde”:

In this poem, McClure expresses his dismay at collective indifference to the natural world: ‘I have been in a spot so full of spirits/That even the most joyful animist/Brooded/When all in sight was less to be cared about/Than death.’

Concern for death distracts from the more deserving task of appreciating and ensuring life’s continuation. Whilst sharing with Artaud a belief in a duality of the spiritual and the physical, according to McClure, the latter is not the barrier to the former as it is in some of Artaud’s work. McClure writes in a comment on the poem, ‘I wanted to join Nature not by my mind but by my viscera – my belly,’ and what remain resolutely separated by the metaphysics of Artaud’s later writing – the physical and the spiritual – have the potential to combine in McClure’s. Concern for the natural world in the immediate present replaces Artaud’s hypothesising about the arrival of a miracle.

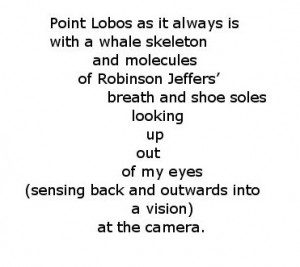

McClure was also inspired by Hua-Yen Buddhism, which is also known as the Flower Ornament school. This school of thought differs from Western viewpoints that separate datum of experience; Hua-Yen unifies datum by analyzing relationships. This is somewhat related to physicist Michael Faraday’s “an electric charge must be considered to exist everywhere” and Alfred North Whitehead’s paraphrase of that concept, “the modification of the electromagnetic field at every point of space at each instant owing to the past history of each electron is another way of stating the same fact.” This reminded Paul E. Nelson, who wrote “Inside Dolphin Skull,” of the second part of that poem, titled “Portrait of the Moment”:

Nelson points out:

The history of the electrons that once made up the California poet to whom McClure refers, and the field of energy that represents, along with the sense of honoring the debt McClure owes to Jeffers as a California poet who preceded him. These are elicited in the projective act as Whitehead understood and which McClure has mastered, aligned with a Hua-Yen world view.

From animism to meat science to molecules, McClure’s unique wordsmithing has always broken the walls we build between us and nature.