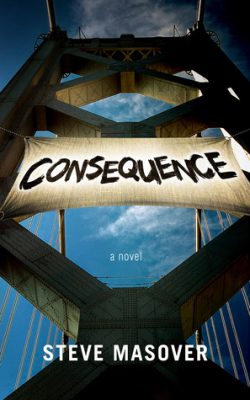

Thanks to Steve Masover, author of Consequence, for taking time out right around the holidays to talk with us about his newest novel.

Thanks to Steve Masover, author of Consequence, for taking time out right around the holidays to talk with us about his newest novel.

Mary: For starters, I always like to look at the background of authors whom I interview. You are an author, activist, and information technologist–born in Chicago and later living in California. Can you go back to the beginning? What early experiences led you to the life you lead? What authors inspired you?

Steve: Those are big questions to answer. I’ll start by saying that I believe personality is something of a mystery, too complex to be untangled into neat, causal lines. With that disclaimer, for a very long time I’ve been drawn to writing as a way to contribute back to the pool of mind-expanding and soul-engaging experiences to which reading lends access–to repay in-kind some of the debt I’ve incurred over a bookworm’s lifetime, to be part of literary conversations in which humankind has engaged for millennia. Thinking about the roots of my activism I suppose I’d point to my parents’ idealism and aspiration; a sense of personal responsibility for making a better world that was tucked into almost every facet of life and culture to which I was exposed growing up on the South Side of Chicago in the 1960s and in the 1970s San Francisco Bay Area; and an empathic sensitivity that sometimes seems too thin-skinned, but as near as I can make out is both native and nurtured. Information technology … the simplest truth is that IT turned out to be a place I could plug my facility with logic and organization into constructive aspects of the economy–most recently, and for the longest stretch of years, that has been in support of public education and research at UC Berkeley.

On the non-fiction end of the bookshelf, I think that reading Dalton Trumbo’s Johnny Got His Gun as a twelve year old, just months after the Ohio National Guard killed four students during anti-war protests at Kent State University in 1970, cemented an already-forming belief that war is the stupidest and most horrific way to resolve any human conflict. That was a pivotal book for me. Another was Paul and Anne Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb, which I read sometime in the mid-70s. The Ehrlichs opened my eyes to the cascading effect that humans as a species could have, and are having, on the biosphere, whose fate is our own. I still find their core message immensely powerful and fundamentally true, despite the torrent of valid criticism aimed at the Ehrlichs’ particular predictions and tone.

During those early, formative years I was also reading and re-reading J.R.R. Tolkein’s The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings, which cultivate the concept that ordinary folk can and must step up to responsibility for a world far greater than what is familiar … and moreover can make critical and even heroic contributions to that greater world. One can argue that fiction in general nurtures this concept, examples from Pat Barker to Amanda Coplin to John Steinbeck are too numerous to list. Even novels in which the protagonist fails, or is saved or transformed by external forces–think William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, George Orwell’s 1984, Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim, or Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End–all books I read before graduating high school–even fictions like these embed a reader in the life of a person having dramatic effect on or playing a dramatic role in a world, within whatever bounds that world is drawn. Fiction feeds a longing in us to be people whose existence matters.

And then there’s poetry, which I came to in a serious way in college and afterward. William Wordsworth for his immersion in the natural world’s wonder, and for vividly describing nature’s formative influence on his character and sensibility. T.S. Eliot, especially The Four Quartets, for synthesis of myth and moral obligation. Gary Snyder, perhaps most of all, for his attentive humility and for the long view of human culture expressed not only in his poems, but in his essays and letters as well.

Mary: Your short fiction, prior to Consequence, has been published in various literary magazines and you have helped to write a screenplay. These works appear to contain messages that call for social or environmental justice. Has a reader ever responded with a changed viewpoint, and how do you think fiction is a good conduit for relaying such concerns?

Steve: One of the most rewarding responses I’ve had to Consequence so far was from a student with whom I’ve been working on climate change issues at UC Berkeley. He told me that relationships between the activists portrayed in my novel helped him understand the importance of building friendship and support among people engaged in activist work: it’s not just about the issue, it’s also about the community. In the spring semester he wants to translate his insights into a more conscious, sustainable, and effective approach to environmental justice work on our campus. Another deeply appreciated response came from the wife of a fellow writer, who had the idea before reading Consequence that San Francisco activists could be written off as idealistic hippie burn-outs. I was moved–not to mention relieved–to learn that through my novel her attitude changed, having gained a more nuanced understanding of people who engage in progressive activism.

Non-fiction is key to laying out information and argument, which is certainly fundamental to pursuit of social and environmental justice, and to changing people’s views. But information is powerless against an impermeable mind and a closed heart. Honest fiction grounded in the real world is a way to convey information and perspective past barriers people erect against ideas they have dismissed, or ideas they are afraid to consider or feel. Empathy is the bridge past those barriers, and empathy is fiction’s strongest suit.

Mary: Your political activism began in the fifth grade. Describe how you were inspired and what things you accomplished.

Steve: I’d say that political activism is what people resort to when success around critically important issues doesn’t come easily, or through more mainstream political processes. Accomplishments aren’t the inspiration: more often lack of accomplishment is the inspiration. So I appreciate that your question distinguishes between the two.

What inspires me to political engagement are hard problems with very high stakes, and a political mainstream that isn’t effectively addressing them. At the same time, I can look back and see that my own work as an activist has–not always, but in some cases–contributed to real change that matters deeply. Being able to see that effect does support and strengthen my resolve and commitment.

The Vietnam War Moratorium took place in the fall of 1969. I was ten years old, but I participated in it by wearing a black armband in solidarity with millions of other antiwar Americans, and I think of that participation as my first foray into political activism. Fast forward to a rally on the Berkeley campus in the 1980s, I’m not sure I remember the issue. Maybe it was an anti-nuke rally, maybe a rally opposing U.S. intervention in Central America. In any case, former U.S. Defense Department analyst Daniel Ellsberg took a turn at the microphone and spoke about how that nationwide moratorium in 1969 dissuaded President Nixon from deploying nuclear weapons against the city of Hanoi, because the president feared that American cities would become ungovernable if he dropped nuclear bombs on Vietnam. Ellsberg’s words, and the authority he had as a former DoD analyst to tell this story, hit me like a bolt of lightning. It was the first time I had evidence I could really hang onto of the power and the gravity of playing even a small part in a just cause. When Nelson Mandela visited Oakland and acknowledged the impact to his struggle in South Africa of UC Berkeley’s anti-apartheid movement (in which I had played a part)–that was another moment that has sustained my lifelong commitment to social justice. I look back at a 1989 blockade of the Golden Gate Bridge in which I participated during the darkest years of the AIDS epidemic–as friends, comrades, and lovers were dying every week and President Reagan wouldn’t even acknowledge that AIDS existed–and look now at the enormous gains made in both treatment of HIV disease and prevention of its transmission. It’s not enough gain, not yet … but we live in a fundamentally different universe with respect to HIV and AIDS than we did in the 1980s. That too is a change to which my small part contributed.

Mary: Speaking of political activism, that is really one of the central ideas in your newest novel, Consequence. I think that there are levels of activism, and activists tend to go to stronger measures when more passive (marches, protests, and raising awareness via the media) methods do not work. I think of the 1990s, for instance, when the biggest act of civil disobedience at that time took place in Canada as activists were trying to stop clearcutting of the temperate rainforest in Clayoquot Sound, British Columbia. They went so far as to set up blockades so that loggers could not get in, and were met by violence from local law enforcement, which, in turn, drew the support of the population at large.

In your book, it goes even further than just setting up blockades–and the reason is because nothing else works sometimes. We can look back to Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang for examples of monkey wrenching (any activism, including more provocative acts of sabotage). Sabotage happens when people are desperate to save the wild, and nothing else is working. Consequence is not afraid to ask the hard questions in the context of the fate of our humanity. In fact, Doug Peacock, who was the real-life model for the character George Washington Hayduke in The Monkey Wrench Gang, said of your book: “Here is a carefully crafted book about the necessity, and danger, of taking personal action in the 21st century. … Steve Masover’s characters ooze humanity. … The villain of Consequence happens to be genetic engineering but it could have been any current social or environmental issue. The premise, absolutely believable today, is that life on the planet is threatened and that battle waged by this novel’s characters will make a difference. … This is a human story shot in the ass with ideas.”

That’s quite the kudos–was it scary to write about extreme environmental activism? How so?

Steve: Was it scary? Yes and no. There were times when I set the nascent manuscript of Consequence aside, convinced that there was no way to bring a book that treats eco-saboteurs sympathetically into a world so convulsed as ours has become in light of mass murders perpetrated by death-cult fundamentalists, in September 2001 and since. I have to admit I felt a little shaky as I conducted research on the technical aspects of sabotage being planned by characters in Consequence … I think there’s a pretty good chance that some of my search engine queries are enshrined in some digital folder archived by the NSA or its ilk. But I ultimately decided that it would be foolish to get wound up over any of that. I’m not a saboteur, I’m a writer. And I was conducting research for a work of fiction, not to plan anything in the real world.

The question of what risks a person can and should bear for what reasons is something that Chris Kalman, the protagonist of Consequence, struggles with throughout the novel. At a certain moment, when he is weighing whether or not to throw in with the saboteur who is recruiting him, Chris recognizes that If people like him—people willing to take risks—failed to force change, then change wasn’t going to happen. The fact that something is scary or risky isn’t always sufficient argument for stepping away from it.

Mary: Edward Abbey took on development in the American southwest. Your book’s profligate is the field of genetic engineering. While genetic engineering may have good uses (do you think?), Greenpeace says:

While scientific progress on molecular biology has a great potential to increase our understanding of nature and provide new medical tools, it should not be used as justification to turn the environment into a giant genetic experiment by commercial interests. The biodiversity and environmental integrity of the world’s food supply is too important to our survival to be put at risk.

Have you any real-life experiences in GMO activism?

Steve: My own direct experience in GMO activism has been limited to participating in marches and demonstrations, like the global March Against Monsanto in Spring of last year. On the other hand, I have written about genetic engineering, among many other issues, on my blog, One Finger Typing and on the political community site Daily Kos.

I’m often careful to point out that Consequence is about an activist community more than it’s about a single issue. That said, the issue on which the characters portrayed in Consequence are focused during the novel’s timeframe is indeed genetic engineering. Specifically, they’re organizing against biotech agriculture that savages incrementally evolved, self-stabilizing ecosystems by imposing crudely mutated monocrop on vast landscapes–monocrop dependent on poisonous industrial chemicals and unconscionable quantities of fossil fuels to produce inferior food and rapacious profit. (Sorry, does that sound like I’m taking sides?)

I do see infection of Earth’s biosphere with genetically modified organisms as one of the worst among a host of toxic human activities, because it throttles a dynamic bioequilibrium that has taken hundreds of millions of years to evolve and replaces it with living systems whose side-effects are not understood even by the scientists who mutated them. GMOs are a compelling topic for fiction because storytelling has a long history of illustrating how hubris tends to go badly. I’d say that pretending we humans are qualified to reinvent, repurpose, patent, and exploit life is textbook hubris.

Mary: I came across a good quote by Grammy winner John Luther Adams in Slate Magazine. “As a composer, I believe that music has the power to inspire a renewal of human consciousness, culture, and politics. And yet I refuse to make political art. More often than not political art fails as politics, and all too often it fails as art. To reach its fullest power, to be most moving and most fully useful to us, art must be itself.”

I think he’s saying that the art must be art first before anything else. And, from what I’ve read, your book fits true art as it’s highly suspenseful and gripping, a page-turner that the reader cannot put down. I agree, and wonder–this may help other writers really inspired to save our natural world–how to write well without offputting the reader with didactic and preachy narratives. How did you accomplish this, and what was your writing process?

Steve: The temptation to bury story beneath preachy exposition can be both strong and perilous. In early drafts of Consequence I sometimes did stray over that line. My own red pen and advice from early readers were the brakes that kept my novel from veering into polemical screed territory.

I’d say the key for a writer is to remember that stories are about characters and plots, and that abstractions and ideas (including political abstractions and ideas) only fit where they deepen character or advance a plotline. If the point of a passage is merely to explicate ideas, a novelist needs to challenge its inclusion in a story. Does the passage truly open a character to a reader’s sympathy and understanding, and does it do so in a way that can’t be better accomplished through dramatic incident? If the answer to either of these questions is ‘no’, that passage might belong in another book, perhaps a work of non-fiction or in a magazine article or a blog post, or just buried in a file box of old drafts. It’s as simple as that, which doesn’t make cutting those carefully crafted ideas and arguments out of a novel manuscript any easier!

I think it’s also essential to remember that no single book will make The Everything Argument. Inspiring readers to change humankind’s relationship with our natural world is a multi-volume, many-author project. Some of those books are going to be fiction, others non-fiction. There’s no sense trying to cram the whole teeming universe into a single novel!

Mary: I agree, and think that your writing advice is very helpful as we try to imagine our future and our present–looking at what we can be, what the Earth should be like–and tell the story in a way that involves humanity, emotions, appeal, rather than just fact. It takes many voices.

Finally, what’s your next project?

Steve: I have two in the oven, both in pretty early stages of gestation; but I’m not one to describe unfinished projects in great detail. The first is a collection of short fiction, some of it previously published and some of it new. One interesting feature of the collection will be inclusion of short-story prequels to Consequence, and also prequels to my second novel (which won’t be finished for a while yet … I don’t write fiction speedily). Readers can expect that second novel to explore how humans grapple with the damage we’ve already done to our environment, and how this struggle to undo the harm we’ve collectively inflicted echos and refracts in our lives as individuals.

Mary: I’m looking forward to it! Thank you for this outstanding discussion. I’ve been researching the field of eco-fiction for a while and feel like I’ve learned a whole lot from your perspective.

This was a great interview that covered so much interesting territory. Thanks, Steve and Mary!