Part XI. Women Working in Nature and the Arts

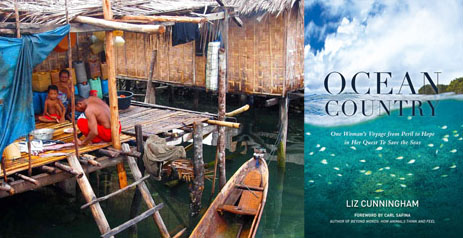

Liz Cunningham is the author of Ocean Country: One Woman’s Voyage from Peril to Hope in Her Quest to Save the Seas (North Atlantic Books) and Talking Politics: Choosing the President in the Television Age (Praeger). Her work has appeared in numerous publications, including Alternet.org, Earth Island Journal, GreenBiz, Times of the Islands and The San Francisco Chronicle. She serves on the board of Outward Bound Center for Peacebuilding and is the co-founder of KurtHahn.org, the online archive for the founder of Outward Bound, Kurt Hahn. Her next book, Every Breath, will chronicle the lives of amazing breathers such as sea lions and whales and the biological reciprocity we all have with the ocean through each breath we take—over 50% of the oxygen in each breath comes from marine plants and algae.

Mary: Thanks for joining our “Women Working in Nature and the Arts” series and congratulations on your new book Ocean Country: One Woman’s Voyage from Peril to Hope in Her Quest to Save the Seas (North Atlantic Books, September 2015). You received your B.A. in Human Ecology and worked as a writer and editor for 15 years, culminating in a book of interviews, Talking Politics: Choosing the President in the Television Age (Praeger), which examined the role of television news in presidential campaigns. Tell us about some of the exciting moments about that time of your life.

Mary: Thanks for joining our “Women Working in Nature and the Arts” series and congratulations on your new book Ocean Country: One Woman’s Voyage from Peril to Hope in Her Quest to Save the Seas (North Atlantic Books, September 2015). You received your B.A. in Human Ecology and worked as a writer and editor for 15 years, culminating in a book of interviews, Talking Politics: Choosing the President in the Television Age (Praeger), which examined the role of television news in presidential campaigns. Tell us about some of the exciting moments about that time of your life.

Liz: One of them was when the Revolutions of 1989 happened. At one point I was in the ABC New Bureau in London and it was crammed with film crews returning from Bulgaria, East Germany, Hungary, Romania . . . ragged with exhaustion. But their eyes gleamed with what they’d seen, mass demonstrations in Leipzig, people dismantling the Berlin Wall.

It was a time of rapid, “almost-unthinkable” change. Becoming a sustainable civilization falls into a similar category for many people, because they “just can’t imagine it.” But Gorbachev could imagine what happened in 1989. He had the necessary vision—that the courage of citizens could set in motion a cascade of events.

Right now we need the equivalent of a Marshall plan to transform our relationship with the Earth, to re-task the global economy. Millions of people around the world are already exercising the necessary vision to do just that—everything from sustainable manufacturing to responsible investing to saving endangered species. It’s important to keep reminding ourselves that we’re capable of this kind of change. Every time one of us joins that bucket brigade of efforts, it strengthens.

Mary: I completely agree and think that so many people are doing the necessary work, just like you. Following your first book’s release, you had a kayaking accident that almost cost you your life. What happened and how did that change you and your career path?

Liz: I was hit by a rogue wave in a whitewater kayak in the ocean. When I came to, I was upside down and unable to release my torso from the cockpit. My arms had been temporarily paralyzed—the area where the nerves in my arms run through my spine had been injured. After a minute or two I thought, “I can’t believe this! I’m dying!” I passed out again. In a dream world, I heard a voice ask me, “Do you want to live?” I said “Yes!” Suddenly my eyes snapped open. I felt a rush of tingling, feeling my arms. I pushed my torso out of the kayak, and there I was on the surface, coughing water out of my lungs.

Ever since then I’ve had a much more heightened sense of how precious each moment is. I still get up each day and marvel that I have feeling in my hands. It still feels like a miracle.

After the kayak accident I was terrified of the ocean and yet I longed for it too. That got me curious. What is it about the ocean that I love so much? Why is it such a profound force? Over time I realized how deep my love for the sea was and that writing about ocean conservation is a way for me to combine that with helping the world become a better place.

Mary: In a nutshell, what are you seeing in our oceans and what are your major concerns?

Liz: The damage to the ocean and the Earth puts life as we know it in grave danger. Among the major driving forces are marine debris, overfishing, ocean acidification, pollution, and warming seas. But for each one of these issues there are legions of people working on them. For my research, I cast a wide cultural and geographic net from Southeast Asia to the European Union. You didn’t have to look far to find talented, dedicated people coming up with solid solutions: fisheries reform, marine protected areas, waste management practices, coastline restoration, on and on. The more we support these people, the more we become a part of their efforts, the more hope there is for the future. The bottom line? There’s a tremendous need for decisive action, but there’s hope because we also have a powerful battery of solutions.

Mary: Were there influences while growing up that inspired you to work to save the oceans?

Liz: One of the biggest was my grandfather’s brother, Kurt Hahn, who was the founder of Outward Bound. I write about how he often said, “The passion for rescue reveals the highest dynamic of the human soul.” It unleashes strengths we don’t even think we have—we exceed ourselves, everything we are, have been, can be, comes to bear in moments like that.

In grappling with the enormity of the damage being done to the seas, the passion for rescue became a lodestone for me—a point of orientation. I needed to refuse to be blinded by the glare of how much devastation is occurring and find a path forward, find my place in the effort to do something about it.

I realized that “yes” moment I’d experienced in the kayak accident was the passion for rescue. I would not be alive today if not for that “yes”—that wild, beautiful energy that can turn things around, even when you think you’ve passed the point of no return. There is a parallel “yes” in the people around the world working on behalf of the Earth. The people I write about in Ocean Country—conservationists, fishermen, sea nomads, scientists—they taught me that the heart of hope is the passion for rescue.

Mary: What did it feel like to create this living journal of a piece of your life, given that we all have to worry about the state of our oceans?

Liz: Well, I wrote with two clocks ticking loudly in my mind. One is the urgency of crises we are facing. Ocean Country is very much a call to action. And the other clock . . . ever since the kayak accident, I’m still haunted by that sense of how precious each moment is.

So you have the urgency of the issues, that we can’t have enough voices on that—that clock ticking louder and louder. And then the sense of each moment as a gift—as long as you’re alive, there are possibilities in each moment. I asked myself, “How would I write as if I only had a day, a week, a month to live?” Ocean County was my answer.

I’d learned so much from the people I wrote about, what they’d taught me about action, about working together to beat the odds. They didn’t teach me how to have hope, they taught me how each of us can become it.

It’s still a mystery to me, a beautiful mystery where the words will go and how others will take them up into their own lives. But I’m definitely getting pings back from readers that the “transmittal has been received.” That’s very rewarding.

Mary: Liz, your book is beautiful inside and out, and I want to thank you for your life’s work and for doing the research and writing to share it with us. Transmittal has been received, and your book is eye-opening and powerful. It was so nice having this talk. Thanks again!

More information about Ocean Country is available at:

http://lizcunningham.net/ocean_country_the_book/

Twenty-one percent of royalties are being donated to the New England Aquarium’s Marine Conservation Action Fund. That percentage was chosen because it’s the percentage of oxygen in each breath we take. Over half of that oxygen comes from plants and algae in the ocean. The New England Aquarium’s Marine Conservation Action Fund (MCAF) aims to protect and promote ocean biodiversity through funding of small-scale, time-sensitive, community-based programs.