Part XIV. Women Working in Nature and the Arts

Annis Pratt’s novels are full of passion for the natural world and enthusiasm for the details of everyday life. Her invented worlds are more realistic than fantastic, her fiction speculative about ways to live in harmony with each other and with our planet.

Her earlier books were studies of the way poets and novelists use myths and symbols. Dylan Thomas’ Early Prose: A Study in Creative Mythology (Pittsburgh University Press, 1970) was about pre-Christian Welsh mythology. Archetypal Patterns in Women’s Fiction (Indiana UP, 1981, published in England by Harvester Press) explored 328 novels by women in which she discovered apatriarchal alternatives latent in women’s literary texts, subversive values of control of their sexuality, intellect inventiveness, love of community, and a marvelously creative but practical competence. In her most recent nonfiction book, Pratt compared the way women and men poets approach Medusa, Aphrodite, Artemis and Bears in four hundred poems from England, the United States, and Canada, drawing upon the Europagan background underlayering classical goddesses. Dancing With Goddesses: Archetypes, Poetry and Empowerment (Indiana UP 1994, distributed in England by the Open University Press) led her to the discovery that gender differences are less important than a common quest for bodily and ecological healing.

-Read more at Annis Pratt’s website

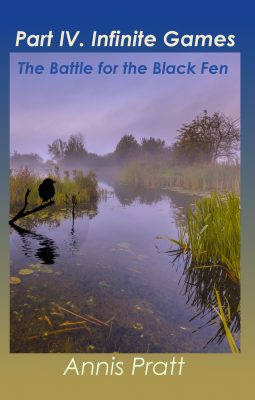

Update: Moon Willow Press is publishing the fourth novel in the Infinite Game Series: The Battle for the Black Fen. The finale is out now. See Amazon.

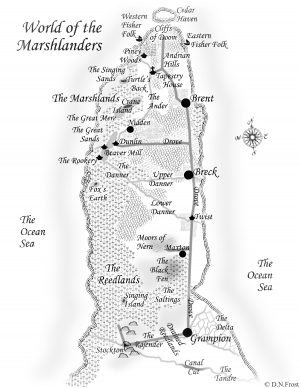

In our talk with Annis, we’ll focus on her Infinite Games series, The Marshlanders, Fly Out of the Darkness, The Road to Beaver Mill, and The Battle for the Black Fen. These are works of speculative fiction in a real-world setting, written for adults and young adults.

Mary: Hi Annis, and thank you very much for agreeing to an interview with Eco-fiction.com. We met in the Ecology in Literature and the Arts Google+ newsgroup, and via this group, I’ve become amazed by your history and your current work. Not just work but pleasure. I realized that you spend summers at a cabin on the Betsie River in northern Michigan. A simple photo shows an old-fashioned lawn chair, binoculars, book, and drink on a deck with a narrow sunlit river flowing by. That picture says so much. It says to me: this is the life I long for, and I’m sure I’m not alone. Your site is even titled, “The Worlds We Long For.” Yours seems to be a life where nature is central to a person’s existence, where the rat race is somewhere else. How did you get to that place?

Annis: Yes, nature is central in my life–being by the river or out in the woods has always been the way to renew my soul. I wonder if my love for nature has to do with spending every winter of my school years in Manhattan, making me was more aware of the contrast from city living than my country friends? The world I long for is not a retreat, however, but a place where we can sustain human life without damaging our environment. Earlier in my life, I longed for a world where women could develop our full capacities; even though the forces out to destroy our beloved planet are huge and frightening, seeing many of our feminist goals come true makes me hopeful for our environmental activism

As for the rat race, I have been there all right; life in academe, given the feminist world I longed for, proved intense and always exciting. I fought against sex discrimination for myself and my women colleagues at the University of Wisconsin while enduring twenty years of a commuting marriage after being blacklisted for filing a sex discrimination complaint against the University of Michigan.

I got to my present place of contentment by retiring early to write eco-fiction and devote more time to community activism–first in race relations, then as a grass roots organizer for public transportation, and now as an environmental advocate.

Mary: Please tell us more about your incredible background, your years of teaching as a college professor, and some of your earlier books. Also, which fiction writers influenced you?

Annis: I loved college teaching, where I developed an experiential and student-centered pedagogy to introduce women’s, Black, and Native American literatures that had never been included in the curriculum.

All of my non-fiction books are about archetypes, symbols, and myths that recur in folklore, poetry, and fiction. My first feminist literary article was “Women and Nature in Fiction,” where I discovered a special relationship between women and nature in stories like Sarah Orne Jewett’s “A White Heron.” This grew into my retake on Joseph Campbell’s descriptions of the “quest of the hero” and Carl Jung’s patterns for “rebirth and transformation,” demonstrating significant differences for women. Archetypal Patterns in Women’s Fiction was based on hundreds of novels by women while Dancing With Goddesses is a systematic comparison of over four hundred poems by men and women.

Would you believe that in all my time at Smith College and Columbia University I was assigned only one or two short stories by women and a novel by Virginia Woolf? It was in my 30s and 40s that I was inspired by writers like Sarah Orne Jewett, Doris Lessing, and (my all time favorite) Margaret Drabble, but these were less direct influences on Infinite Games than J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy.

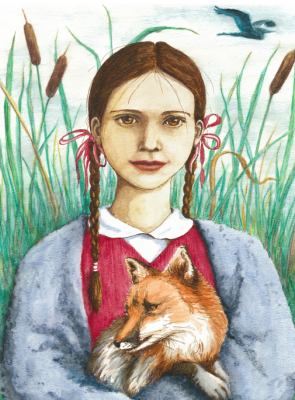

Mary: When I began reading the Infinite Games series, I felt like I’d met an old friend with a story set in a type of pastoral world. The main character, who starts out young and grows older throughout the series, is a strong female who, when young, reminds me of my childhood heroes such as Scout Finch (To Kill a Mockingbird) or Anne Shirley (of Green Gables) or Juana Maria (Island of the Blue Dolphins). Finding such a heroine felt comforting. She is imaginative, strong, playful, and loyal. How did you invent this character?

Annis: The concept of infinite games has to do with a paradigm change from a power-over, winner-take-all attitude of dominating people to a power-with, win/win attitude of collaboration and communality. It derives from James P. Carse’s Finite and Infinite Games.

I got the idea of modeling my self-sustaining wetlands community on the people of the East Anglian Fens when my Native American students, irritated by Euro-American usurpation of their spirituality, quipped, “Don’t you have some Anglo-pagan ancestors you can research, Dr. Pratt?”

About Clare–she is almost entirely autobiographical. All that playfulness and perpetual motion, eagerness to be loved amid plunges into nightmares and gloom, are based on my childhood as a cheerful little soul growing up in a cold and distant family. With maturity, I realized that historical gender norms had crippled my mother’s psyche. My understanding and forgiveness led me to develop Margaret as an affectionate and loving mother who pretends to reject Clare on order to save her from persecution as a healer’s daughter.

Mary: Well, thank you for creating the wonderful, adventurous Clare.

In your story, commerce and industry are seen as ruinous of nature and the land. The story is set in an earlier time that we may think of as simpler, less complicated, and one in which the protagonists revere nature. This is important to you, respecting nature and living without a big consumer mindset. How do you think literature can carry such themes by telling great stories rather than preaching? What kind of genre does your book fall into, and do you think the publishing industry has a good category for nature fiction?

Annis: Figuring out what genre I am writing in has been a challenge; I am relieved to discover it has been eco-fiction all along! The pastoral, historically, idealized rural life; it was a kind of escape genre for urban sophisticates. “Arcadian” in eco-fiction also suggests a rosy view of nature. My genre is more Arcadian/dysArcadian, or utopian/dystopian, with the machinations of the merchants and their allies always threatening my Marshlander communities. So my theme isn’t commerce and industry vs. a simpler time closer to nature. The Marshlanders have a viable economy producing fish and flax for market and raising sheep for wool under agreements with local farmers. They barter their goods but also use coinage to purchase items they can’t produce themselves. My hero William is an industrious inventor of irrigation systems to help his farming community; his enemy Anthony is a wetlands engineer scheming to drain the marshes for wealth and profit. Their difference from the early modern investment capitalism rising all around them is that the Marshlanders’ economy is collaborative (win/win, power/with) rather than competitive (win/lose, power/over).

So my Arcadian eco-fiction is less a going back to simpler times than a parable for what Joanna Macy has called “The Great Turning,” a name for the essential adventure of our time: the shift from the industrial growth society to a life-sustaining civilization.” (www.joannamacy.net)

Having said all that, The Marshlanders and its sequels just poured out of me; I rushed to my computer in the morning to see what Clare would get up to that day. I come from a long line of story-tellers; stories engage people’s hearts by drawing them into worlds; lecturing talks at folk about things in the lecturers’ head and usually fails to draw engage their audience as whole beings.

My hope is that the eco-fiction genre will catch the hearts of readers in this time of climate fear and environmental malaise.

Mary: The very start of The Marshlanders has women who use herbs to heal being kidnapped and abused. It is like the Scarlet A of those who understand nature’s gifts (instead of those who break strict sexual laws). No doubt there is a real history of such “witches” who used herbs as being evil, un-Christian, and treated as outcasts, or, worse, hung and killed. In your research, did you come across any real stories that really haunted you? I’m not sure what we call these normal people now–pagans, witches, pantheists? But in reality they were just normal people using such things as herbs to treat medical conditions. How did normal people become so wrongly stereotyped and outcast?

Annis: Oh yes, witches are very empowering female archetypes. They became great heroes to my University of Wisconsin students where local witches and covens used to visit the course I offered on Women’s Spirituality. In England, these “wise women” provided healing and midwifry until the 14th century, when their practices were declared illegal. Poet Robin Morgan, with whom I corresponded about the Unicorn Tapestries (c. 1500), was the one who suggested that many weavers–men as well as women–were witches who hid their herbal recipes in the mille fleurs design making up the backgrounds of their tapestries. As the modern era developed, women who showed any independent talent at all became more and more repressed, and that’s how “normal people became so wrongly stereotyped and outcast.”

Mary: How close to finished is your Infinite Games series, and can you talk more about what’s happening in the entire story?

Annis: My Infinite Games series is complete, comprising The Marshlanders, Fly Out of the Darkness, The Road to Beaver Mill, and The Battle for the Black Fen. In the second volume, Clare reaches safety at Cedar Haven; the third is about her daughter Bethany’s adventures and misdeeds; and the final volume brings all of my characters together for the decisive battle to determine whether their enemies will finally drain their entire habitat.

Mary: I am excited to read more!

Well, I really do envy you for having that place on the river. I grew up in the Chicago area, and we often went to northern Wisconsin and Michigan during the summers, and my dream was to have a cottage on the Menominee River, where we spent many summers wild-water rafting. Of course, who knows, maybe it is different now than it was when I was a kid and teenager. Do you do a lot of writing up there?

Well, I really do envy you for having that place on the river. I grew up in the Chicago area, and we often went to northern Wisconsin and Michigan during the summers, and my dream was to have a cottage on the Menominee River, where we spent many summers wild-water rafting. Of course, who knows, maybe it is different now than it was when I was a kid and teenager. Do you do a lot of writing up there?

Annis: Over the years, I have done some writing at the cottage, but I prefer to use it as a total retreat from the writing and activism that occupy my days “down state,” as we say in Michigan.

Mary: Before we close, please tell us about your fascination with boats. On your blog, you quote Kenneth Grahame, The Wind in the Willows: “Believe me, my young friend, there is nothing – absolutely nothing – half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats.”

Annis: Though my mother used to say that she “tucked the love of nature under my belt” to help me through hard times, it was my father who inspired my fascination with boats. He and his brother took an “oath of paganism” back in the 1900s, which, for them, involved the life-long love of the ocean. Our summer home was next to a dock on Long Island Sound; at one point we lived on a boat in the harbor there. As a teenager I sailed with my friends from Southern Connecticut to Northern Maine, and I never let myself become landlocked in the Midwest where first canoes and then kayaks became my passion.

Mary: Amazing. Your entire life story is intriguing, and the books you have written are a mirror to the legacy that is your life. I look forward to reading the rest of the Infinite Games series, and thank you so much for taking the time to talk with Eco-fiction.com!

Originally published August 17, 2016