Originally published July 8, 2014. Rebooted July 17, 2025 into the World Eco-fiction Series.

Originally published July 8, 2014. Rebooted July 17, 2025 into the World Eco-fiction Series.

Updated: This novel is now a movie.

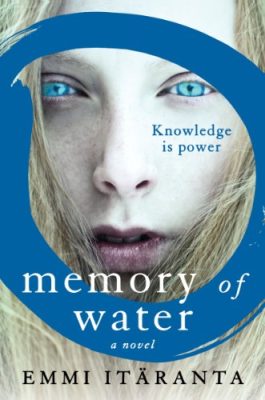

I want to thank Emmi for this wonderful interview. My first pleasure was reading her book, Memory of Water. The novel takes place in the future after climate change has ravished economies and ecologies, and made fresh water scarce. When reading, you just want to drink a glass of cold water and revel in it as if it is the last great thing you will ingest. One could never take water for granted again after reading this novel. The main character, Noria, is a young woman learning the traditional, sacred tea master art from her father. Yet, water is rationed and scarce in her future world. Her family has a secret spring of water, and, as tea masters, she and her father act as the water’s guards, even though what they are doing is a crime according to their future world’s government, a crime strongly disciplined by the military.

My second treat was talking with Emmi via e-mail, which culminated in an interview with this amazing author.

Mary: The book’s title, Memory of Water, is a double entendre. I think as a reader, I first realized that in this future dystopian world, remembering the importance of water is key to respecting it as a life-force that we must protect and conserve today. Then, at one point, your beautiful prose illustrates that water has its own memory. Throughout the book, you hauntingly show that water is in all we are, all we ingest, all that is life, in everything else that is alive, too, even in the stones. Every place water is, or has been, it “remembers” its history. I loved this idea, and wonder if you could talk a little bit about it.

Emmi: One of the central themes of Memory of Water is continuity: of tradition, of culture, of history, of knowledge, of the relationship between humans and their environment. The story explores the impact of disrupting these continuities. The society portrayed has lost part of its history and therefore does not know how to build a better future. Meanwhile, the continuity of the tea masters’ tradition has become a double-edged sword, which both maintains vital resources and monopolizes them. I chose water as the central element of the story because of its continuous nature: it is always changing, but never disappears. It can revive or destroy, and it is something much older and more powerful than humans. I felt it was a potent metaphor for many things, and in the course of the writing process I began to think of it as a living being, one of the main characters of the book.

Mary: Just as when a person dies and water leaves it, so does the tea ceremony end when the water is gone. This is emphasized in the novel and is a simple but powerful way of looking at water. This question is two-fold. One is out of curiosity: have you had experience in hosting or attending a tea ceremony, and do its attendees respect the power of the water? Second, is the tea ceremony a metaphor for life, for everything that holds water? When the water ends, our life’s ceremony is also over.

Emmi: I have attended a Japanese tea ceremony, and my impression was that every detail is given a lot of thought and attention, water included. The idea that the purity of water is particularly important for tea-making is something I first encountered when reading about the history of tea in China. So it is not my own idea, but I adopted it for the book and amplified it, because it seemed appropriate for a water-deprived future. And yes, the tea ceremony does become a metaphor for life, and possibly also for different belief systems: if the form is kept immaculate but the essence lost and carved hollow, any belief system or ritual intended as meaningful will run as empty as a vessel without water. This is reflected in Noria’s conflict with the corrupt tea master who judges her graduation ceremony.

Mary: Though I found the entire novel fascinating and gorgeously written, there were several very powerful scenes that I just kept going back to read. These scenes emphasized memory, secrets, reflection, imagination. One was Noria imagining what snow must have been like. Regarding reflection, early in the book there was a scene wherein Noria was looking at a dry riverbed. She imagined past-times when the river flowed with water. She imagined in that past-time a woman standing at the river’s edge, able to see her reflection in the water. Noria wondered if the woman would go home and change even one thing about her life–which I thought maybe eluded to us, reflecting on ourselves, our future, and mitigating climate change and environmental problems. The illustration was perfect. Do you have some thoughts about this particular scene and what you were portraying?

Emmi: Your reading is exactly what I wished to convey. I feel that we live in a culture that is very focused on short-term profit at the expense of long-term impact on our environment, and that people choose to ignore the continuity and interconnectedness of things. It is about seeing the bigger picture, and recognising responsibility. Noria thinks about these things because she has no choice. We do have a choice – what we do with it will inevitably have a bearing on the lives of those who come after us, so I believe we should try to see beyond ourselves and our own short lives.

Mary: Speaking of reflection, it can be shattered in not only water but in mirrors of history that aren’t truthful. Noria and her friend Sanja, when searching through a midden grave, uncover old-world recordings, which hint of a truth stronger than ones given by the novel’s military and superpower China–which, like many governments even today, edit history to “correct the course” that has taken many wrong turns that lead to dystopian or dysfunctional societies. Even the pod books mentioned in your novel are easily revised. The old recordings speak of an expedition in which explorers from another time find lots of fresh water in the “Lost Lands”, a place that is still a mystery to Noria and Sanja. I think part of the problem with climate change is that we have already revised our history and are, in parts of the world, in denial that climate change exists or that it will hurt future generations. Only if we allow ourselves to see the truth will we potentially do better for our descendents. To allow this truth, perhaps it will take some exploring, reflection?

Emmi: I do think that we are often inclined to be in denial about things that are difficult to face and force us to question what we have grown used to taking for granted. It is quite possibly a basic human survival technique; unfortunately, in some circumstances it may actually have a negative impact on our chances of survival. I’m deeply interested in stories that have been left untold and erased from history, and in the reasons behind such erasure. I see this happening with climate change today to some extent. Rather than treating it rationally in light of scientific evidence, many people seem to treat it as a matter of faith. I think this is harmful to any attempts at approaching the matter constructively, because it leads to people cherry-picking only the arguments that support their already-chosen stance, rather than people actually looking at the evidence and drawing their conclusions based on that. Obviously, there are also many economic and political interests at stake, which complicates things. I would like to think that exploration and reflection would help shift the discussion in a better direction; what I don’t know is how to get enough people to explore and reflect.

Mary: A Twilight Century exists in the novel, an era in which oil ran dry before Noria’s time. Before that was a resource oil war in the Arctic after glaciers there completely retreated to the seas. I think what you imagine will take place; already several countries are competing for drilling rights as melting glaciers are making pathways via the sea to this oil. I think the future, as it takes place in your story, is what will really happen in many cases. Where you live now, in Finland, have you seen your region vie for oil in the Arctic?

Emmi: In fact, I live in the United Kingdom, but I’m originally from Finland and go back there a lot. I’m not aware of any interest in the Arctic oil resources in Finland, and I would be surprised if Finland joined the race to claim them. However, I have no doubt that our neighbours Russia and Norway will. Personally, I find it rather chilling that this is happening.

Mary: Your book is slow and persistent. Every detail you shape has meaning. You incorporate rocks and winds and insects and all matter of life into the plot, the movement of the story. The narrator, Noria, is keen and observant and caring and strong, a great heroine for a young adult audience but meaningful and inspirational to people of all ages. She is observant of the shape of time, water, and memories. She feels that imprints of the past are strong currents around her. I guess this isn’t a real question, but my own observations that your writing excellently portrays memories, secrets, and imprints. Can you talk a little about deciding on how these factors carve your novel?

Emmi: One of the first things I knew about the novel when I began writing it was that I wanted it to be a story about facing one’s own mortality. In some ways, while Noria’s understanding of the world widens, the physical boundaries of her world become narrower. She is therefore forced to find meaning and purpose in the smallest details and observations. Also, because the tea ceremony is all about attention to detail and Noria is a trained tea master, I felt it would be her natural way of observing the world. As for memories and secrets, her family background is heavily shaped by their presence: a tea master’s profession learned and memorised, then passed on to the next generation, and the secret of the water source bound to it. Therefore her awareness of these things would be amplified. And imprints, of course, have to do with the mark people leave on the world, in good and bad.

Mary: When reading your novel, I was able to see things happening. You use a lot of visual clues when describing an event. You use lighting, if you will–shadows, light playing together. Even framing, as in film. You provide textures, details about movement. You have a theater background, so maybe that has also shaped your writing? Could you see your novel as a film? I could!

Emmi: I could definitely see Memory of Water as a film. In fact, as a teenager my dream was to be a filmmaker, and I think my interest in cinema has crucially influenced my writing. If I get stuck, I often imagine the scenes as a film I’m watching. My theatre background has taught me a lot about story structures, dramatic tension and character motivation, but the cinematic approach owes everything to my long-abandoned filmmaking dreams! I would love to see what shape the story would take in the hands of a skilled screenwriter and director.

Mary: I think I’ve asked enough heavy questions for now. What’s next? I think I’ve read that you are working on another project or novel?

Emmi: Yes, I am now writing my second novel. It is not related to Memory of Water in any way, but is a standalone set in an entirely different fictional universe. It could probably be best described as a mystery story with elements of urban fantasy, alternative history and New Weird (or perhaps Finnish Weird). It takes place on an island that is slowly drowning due to floods and where dreaming is forbidden. Like Noria, the main character is a young woman carrying secrets. Hers have more to do with identity, but environmental concerns are present, too.

Mary: Did you know when you were writing that there was a climate change genre?

Emmi: I did not. I remember specifically trying to find contemporary novels about climate change when I was writing Memory of Water, and not finding many – I think Ice People by Maggie Gee, Solar by Ian McEwan and The Carbon Diaries by Saci Lloyd were among the few I came across that dealt directly with the imagined impact of climate change. I would have been overjoyed to come across a website like yours at the time. I think the resources and awareness have made big leaps in the past few years, and today the list would be much bigger. I think I only first heard of climate fiction in 2013, when my book had already been out in Finland for well over a year. The term piqued my interest immediately, and I think it’s a great way of describing certain types of speculative fiction.

Mary: Finally, do you have any other thoughts to add to this interview?

Emmie: Just this: thank you ever so much for the insightful questions, and thank you for the website! It will definitely be one of my go-to places for book recommendations in the future.

Mary: Thanks again, Emmi! I feel very honored to have talked about your book with you, and I know the readers will enjoy your thoughts. Best of luck in your future. I hope we keep in touch, and I’m looking forward to your next novel.

You can find Memory of Water at Amazon. The book was first published in 2012 in Finland; Emmi was compared to Ursula K. Le Guin and Margaret Atwood. The novel was published in English in June 2014.

Author bio

Emmi Itäranta (b. 1976) is a Finnish author who writes fiction in Finnish and English. Her novels have been characterised as lyrical dystopias with strong ecological undercurrents. Itäranta’s award-winning debut novel Memory of Water (2014) has been translated into more than 20 languages. The novel was shortlisted for the Philip K. Dick Award, the Arthur C. Clarke Award and the Golden Tentacle Award as well as being included in the Otherwise Award honor list and among the finalists of Premio Salerno Libro d’Europa.

Itäranta has also published two other novels, The Weaver (US title) / The City of Woven Streets (UK title) (2016) and The Moonday Letters (Finnish edition Kuunpäivän kirjeet, 2020). The awards won by her books include Kalevi Jäntti Prize for young authors, Young Aleksis Kivi Prize, HelMet Readers’ Choice Award, Kuvastaja Award for the best Finnish fantasy book, Tampere City Literary Award and Tähtivaeltaja Award for the best science fiction book published in Finland.

Itäranta lived in the United Kingdom for 14 years before relocating back to Finland in 2021. She now lives in Tampere, Finland, and continues to write in two languages. Find more at her website.

Pingback:What are the best eco books for children and teens? - LitVote

Pingback:Importance of Water – Writing and the Environmental Crisis